|

|||

|

Explaining Colombia 'Solo

vivimos en paz cuando estamos peleando' (We're only at peace when

we're fighting. Story

by Frank Bajak '79 / Illustration by Cecilia Malachowska

/ Photos by Ariana Cubillos

We sat across a thick wooden conference table in his spartan third-floor law office in downtown Medellin, a Colombian city known to the world mostly for drug gangs and a seeming innate proclivity toward violence. Through

the open window we heard the bustle of midday commerce on the street

below. A train glided by two blocks away on Medellin's modern, elevated

metro. The

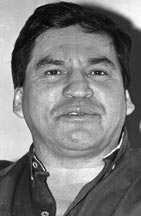

head of a Medellin human rights group whose two previous leaders

had been gunned down in the 1980s, Valle was one of those rare Colombians

unafraid to publicly speak their minds. Valle had accused army generals

and powerful politicians–including the provincial governor

at the time, Álvaro Uribe Velez–of colluding with right-wing

death squads in a murderous campaign against civilians deemed sympathetic

to leftist rebels in towns north of the city, including Ituango,

where Valle had been a councilman.

"In the past three years, during the rule of Dr. Álvaro Uribe, the rivers have been so bathed in blood that we don't know how many dead there are in the country,"the lawyer said. Valle did not offer any evidence implicating Uribe. But enough cases of complicity by security forces in death squad activity had come to light, including in investigations that I, as Associated Press bureau chief for Colombia, had conducted or overseen, that his compassionate rhetoric did not stir incredulity. At the time, Uribe was an outspoken supporter of citizen self-defense units, several of which were involved in murderous excess and collusion with right-wing paramilitary forces. Uribe's office helped coordinate citizen militia activities in Antioquia state, at once the country's most economically productive and most turbulent. That

was five years ago. Uribe is now Colombia's president, inaugurated

Aug. 7, 2002, after being elected on a promise to vigorously prosecute

the war against leftist rebels. He seeks, for one, to double the

army's combat troops to 100,000, with U.S. help. When I met Valle in October 1997, I was a trustworthy foreigner referred by a mutual acquaintance. It was our first encounter, and Valle was providing me with the docket on members of an urban militia, including ex-cops, accused of systematically murdering petty criminals and drug addicts. Before we got down to business, Valle had me switch off my tape recorder and foretold his own violent death. Sure enough, five months later, two men and a woman would march up the stairs to Valle's office, tie up and gag a colleague and Valle's sister, who served as his secretary, in a cramped anteroom. Valle accepted death without a struggle. The assassins forced the lawyer to his knees and shot him in the head. Jesus

Maria Valle Jaramillo left no wife or children. He'd decided years

before not to marry; said he didn't want to cause anyone anguish

when his day came. It has happened again and again in forsaken villages with names like Mapiripan, Puerto Alvira, or Chengue, typically meriting only brief mention on the inside pages of U.S. newpapers. The story is so repetitive as to seem banal: authorities ignore warnings of imminent massacres, then they occur. Garcia Marquez once told me that his fiction, so steeped in brutality, superstition, and febrile hallucination, is not fantasy's child. It is grounded in the sinews of fact, in the history of a chaotic land thin on tolerance where violence is the hardest currency, where living by one's convictions tends to invite death. Law governs little in Colombia, passion more. The social contract pales. Informal compacts sealed with a handshake prevail. Colombia is a land of constantly shifting regional alliances and tropical Machiavellians. As I traveled the country for more than four years at the close of the 20th century, meeting its saints and scoundrels, innocents and cheats, I shed layers of inbred North American optimism, naivete if you like. I learned the Colombian creed: Scruples are a liability. Best to reserve your trust. The late cocaine kingpin Pablo Escobar, I was told, considered that humanity boils down to two subspecies: "el vivo y el bobo"–the con artist and the dimwit. If you're not taking advantage, you're being had. Colombia is a geophysical masterwork and biodiversity gem that remains the global leader in the production and export of processed cocaine. It is also the hemisphere's number-one source of counterfeit U.S. dollars. But those traits only hint at a deeper malaise. Ah, many Colombians will tell you, this nation is unluckily cursed by geography, situated as it is where South America funnels into the Panamanian isthmus, a centuries-old smugglers' crossroads. If it's not outbound cocaine and heroin, it's inbound AK-47s, contraband Marlboros, and Johnny Walker Red. Colombia's fractured geography has always made it a challenge to govern. Yet the essence of the malady is wholly sprung from the species, Colombian intellectuals will tell you. It arises from nearly two centuries of a history in which any serious challenge to the commercial and political axes of power is routinely answered with a corporeal piercing of lead. Just about any time a popular leader comes along who might redeem Colombian democracy, somebody who had something to lose was willing to kill for it. Luis Carlos Galan most famously paid with his life in a 1989 shower of bullets after challenging the Medellin cocaine cartel. In Valle I met a man whose courage made me wonder: Could I possibly have the guts to knowingly write my own death warrant? "One

has to keep going and find his way out of the tunnel. It's the only

way," Valle answered when I asked how he could so deliberately

curtail his own mortality. |

||||

|

back to top |