Poet Werner Söllner Shares Chilling Memories of Life in Romania

His students were enthralled, as much with the stories of his former homeland as with the opportunity to work with a real-life poet. He was equally fascinated with life in America. Both departed in some way changed by the experience.

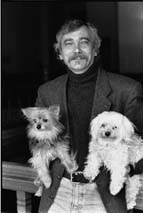

Werner Söllner, a poet and freelance writer who lives in Frankfurt, Germany, was the 30th annual Max Kade Writer-in-Residence, a position funded at Oberlin by the Max Kade Foundation in New York. Söllner joins the ranks of a distinguished group of German authors who have taught here over the years, including Christa Wolf and Max von der Grun. His work, which includes three recent volumes of poetry--Das Land, das Leben (1984), Kopfland (1988), and Der Schlaff des Trommlers (1992)--has won him numerous awards, including the 1985 Andreas-Gryphius Prize for Poetry, the Berlin Stipend for Literary Colloquium (1987), and the 1988 Friedrich Hoelerlin Prize for Poetry.

But like many of his predecessors, Söllner's literary credentials are only one aspect of his rich experience. Along with the skills and sensibilities of a poet, he brought a cultural heritage virtually unknown to most

young Americans.

An ethnic German, Söllner was born in 1951 in southern Romania and grew up under a communist regime that culminated in the long, disastrous presidency of Nicolae Ceaucescu. He earned his MA in German literature at Babes-Bolyai University in Kluj, Romania, and worked briefly as a Gymnasium teacher in Bucharest before joining a children's book press in Romania as a German-language editor. In 1981, he recalls, life in Romania began to go from bad to worse.

"The economy was very down," said Söllner of Ceaucescu's austerity measures. "There was almost no electricity...and that winter, in -20 degree weather with no heating in our houses, we slept in all our clothes.

"Some people would light the gas in their kitchen stoves for heat, but the pressure was weak, so the flame would often blow out during the night and fill the house with gas. Two of my friends died that way. "

Söllner and a group of other writers and artists began to publicly oppose the Ceaucescu regime. In October of 1981, they were ordered to report to the Central Committee for a personal meeting with Ceaucescu himself.

"We tried to prepare ourselves for whatever was to come--arrest, torture, death, whatever," Söllner said. "On that day 24 trembling poets and critics and novelists and artists presented themselves at the Central Committee headquarters. Ceaucescu came in and said he wanted two of us to tell him what we wanted--we had one hour."

In all, the meeting lasted eight hours and 22 of the dissidents spoke.

"We told him everything. We told him no one believed him. But he said nothing. At the end, he stood up, thanked us for speaking so frankly, and told us there was nothing he could do."

After the 1981 encounter with

Ceaucescu, Söllner said he felt increasingly threatened by the Securitate, even experiencing "some unpleasant encounters of the third degree." He fled to Germany in 1982.

In his weekly classroom colloquia and Stammtische, the coffeehouse gatherings he held at his home, Sollner shared with his students some of the personal stories which engender his poems, stories that evoke wide-eyed respect for the man as well as the poet. Drawing on his own experience as a translator, he gently guided the class through a translation of one of his poems, "Fremde Nacht," weighing each preferred word choice with the impartiality of a judge.

"A good poet has no idea of telling us something precise. My poems are very personal", he said. "I tell my students to find their own relationship to a poem. I believe that one poem has as many lives as readers."