|

Issue Contents :: Feature :: New Media, Old Media :: [ 1 2 3 ]

Sidebar: Rocking

the Chip Music

Scene

by Yvonne Gay Fowler

The Talcott Hall dorm room shared by TIMARA majors Cory Arcangel ’00 and Paul Davis ’00 was so littered with computers—particularly old Ataris and Commodores—that visitors had to forge a path just to get through. Though fun, the pair’s computer experiments were also serious business. The Talcott Hall dorm room shared by TIMARA majors Cory Arcangel ’00 and Paul Davis ’00 was so littered with computers—particularly old Ataris and Commodores—that visitors had to forge a path just to get through. Though fun, the pair’s computer experiments were also serious business.

Classically trained musicians—Arcangel in guitar and Davis in harpsichord performance—the seniors were growing tired of their traditional repertoires and began searching for a new style of music. “I taught myself to take apart and re-program the video-game systems of my childhood,” says Davis. “I developed an appreciation of their limitations as instruments and the music that was composed on them.”

Throughout their senior year Davis and Arcangel, joined by Joe Bonn ’00 and Joe Beukman, a friend from Southern Illinois University, tinkered with ways to modify the music on video-game systems such as Donkey Kong and Mario Brothers. Later that year they successfully re-programmed their new, primitive tunes into danceable computerized loops, a technique that would earn them a rightful spot in the chip music scene.

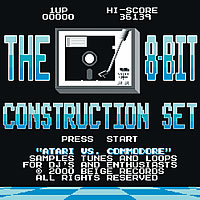

The 8-Bit Construction Set’s scrappy digital sound was completed in 1999 and pressed onto vinyl in 2001. The self-titled LP, released under Davis and Beukman’s Beige Records label, pits an Atari 800 XL against a Commodore 64. The result is an LP of original music that uses pre-existing video-game sounds from Space Invaders, Missile Command, and an Atari commercial with Alan Alda. No overdubs or processing were used, only those sounds from early home computers and video games—“a purist sort of thing,” says Davis, and a welcome move for critics, listeners, and DJs eager to sample new beats.

A reviewer with the Riverfront Times in St. Louis soon voted the record “Best Use of Obsolete Computers,” dubbing it an “audio love letter, an incredible object that both celebrates and examines anachronistic technology.”

Peter Margasak of the Chicago Reader referred to the LP as a “veritable video arcade symphony” and praised the group’s cutting-edge, off-kilter contemporary dance/pop music. In 2003, a New York Times review noted: “In its geek-positive way, the Beige artists deliver subversive messages. They undercut the notion of technological progress and demonstrate ways in which popular forms and aesthetics can be taken out of the control of the corporate game industry.”

Davis now lives in London, where he works as an artist, lecturer, and weekly radio host. Bonn, in Los Angeles, is a sound editor for feature films; his most recent projects include Hidalgo and Terminator 3.

Despite their scattered lives, 8-Bit members occasionally get together to perform or to educate others on getting the most out of old game systems. This fall, Bonn and Arcangel joined Davis in London to offer a four-month workshop series on music production; the standing-room-only sessions offered tips on DJ’ing, VJ’ing, and video hacking. Last spring, when Arcangel was asked to give a video art performance of re-programmed game systems at the Whitney Museum’s 2004 Biennial, he brought along the rest of his bandmates, who spiced things up with a live show. Last year, Davis turned down a composition-performance artist-in-residence position at Carnegie Mellon when it was determined that he wouldn’t be able to include the rest of 8-Bit.

Although progress has been made toward another LP—Davis has laid some tracks with his organ and an Atari system, and other songs have been recorded using Atari and Nintendo systems with an organ and guitar—the friends’ busy careers and a changing chip music scene have made sticking to a schedule almost impossible. Although progress has been made toward another LP—Davis has laid some tracks with his organ and an Atari system, and other songs have been recorded using Atari and Nintendo systems with an organ and guitar—the friends’ busy careers and a changing chip music scene have made sticking to a schedule almost impossible.

Davis recalls his TIMARA senior recital, Hacking the Nintendo Entertainment System, in which he demonstrated how to re-program Nintendo cartridges. “That’s where all of our computer music and art comes from,” he says. “Since we put out our record there has been a huge growth in the popularity of 8-bit, or chip music, as it is now called. The environment is completely different than it was when we were just a few unknown Conservatory nerds in Ohio making a new style of music.

“I don’t know what it was about Oberlin at the time,” he adds, “it was just school, but thinking back on it, it was a really fertile place that fostered creativity in all of us.”

|