Performance Architecture

Working, playing, and music-making in the Kohl Building

(Photo by Kevin Reeves)

With his black, thick-framed glasses, Jacob Silverman, a jazz piano performance major from Abingdon, Maryland, could pass for a young Dave Brubeck. Because Silverman is a first-year student, he missed out on all the excitement when Stevie Wonder, Bill and Camille Cosby, and other luminaries were on campus last May to celebrate the Bertram and Judith Kohl Building’s opening. Nevertheless, the building had enough star wattage of its own to draw him to Oberlin for study.

I can’t even begin to describe to you my excitement for the Kohl Building," says Silverman. "It was extremely significant in my decision to attend Oberlin. I looked at the building’s development every day on the website, and I read about it all the time. I was fascinated by it."

If the Kohl Building is the beacon guiding top young jazz musicians to Oberlin, the energy powering its light is the conservatory’s acclaimed jazz studies program. For Silverman, that meant the chance to study with Associate Professor of Jazz Piano Dan Wall.

"Of all the teachers I had met at other schools, he struck me as probably the most innovative as a pianist and a teacher, with his own views on harmony, melody, and rhythm. Not only that, he’s extremely well studied; he knows so much of the tradition of jazz that he can play like any pianist in history. He is just phenomenal. Every lesson is amazing."

Bobby Ferrazza and the late Wendell Logan tour the construction site that would become the Kohl Building.

(Photo by Michael Lynn)

Recruiting top-flight jazz artists such as Wall, Marcus Belgrave, Gary Bartz, Peter Dominguez, Robin Eubanks, Bobby Ferrazza, Billy Hart, Dennis Reynolds, and Paul Samuels to teach at Oberlin was one way that the late Wendell Logan, who founded Oberlin’s jazz studies program in 1973, built strength upon strength. Logan, who shepherded the program throughout the decades, making it one of the most respected in the country, was honored by returning jazz alums and representatives from every sector of the Oberlin community at the building’s opening, and its lobby is named for him. Sadly, he died just six weeks after its opening.

Bassist and producer Leon Lee Dorsey ’81 was artistic director for the star-studded concert presented in Finney Chapel at the building’s dedication in May 2010, at which he also performed. He is also professor and coordinator of jazz studies at the University of Pittsburgh. Dorsey studied arranging and African American music with Logan, and he recalls those nascent years of jazz study at Oberlin as "an evolution." Dorsey says that he was the first to graduate from the conservatory with a "major" in jazz—but he had to major in classical bass performance in order to earn it. It was not until 1989, when jazz studies became an official major at Oberlin, that a student could begin working toward a stand-alone bachelor of music degree in jazz studies. Dorsey says that in addition to teaching and arranging African American music, "Wendell was running the small and large jazz ensembles. It was a lot for one person to do. As a musician, he was one of the most selfless individuals I’d ever met."

Dorsey says that he and his classmates—writer, composer, and saxophonist James McBride ’79 and trumpeter, trombonist, and composer Michael Mossman ’82—found "what we needed, on a variety of levels, musically and artistically," in Logan, who was a mentor to them and numerous other students. But, Dorsey says, Logan "also helped tweak us as men, shaping us as individuals inside and out. The beauty to me of Wendell was that he was nurturing and a disciplinarian at the same time. He was masterful at figuring out what each individual student needed while being very comprehensive in his approach. That’s an unusual thing for an educator, and Wendell influenced my own teaching tremendously." Dorsey considers Logan one-third of the "triad" of influential teachers who shaped what he became as a person, teacher, and musician—the other two being bassists Richard Davis and Ron Carter.

Just as Logan left his stamp on individual musicians, he also helped to shape an institution. "Music is about great ideas, tremendous ability, and enormous talent, but also a vast amount of hard work," says Dean of the Conservatory David H. Stull. "Wendell Logan single-handedly built a department that became critical to the very nature of the conservatory."

In 1988, Logan hired Bobby Ferrazza to teach at Oberlin, giving the jazz guitarist his first full-time professorial gig. After Logan’s death, Ferrazza, now associate professor of jazz guitar, inherited the mantle of department chair. Last fall he began a new academic term without his mentor at the helm.

"Wendell was many things to me: friend, family, big brother, almost a father at times, certainly mentor," says Ferrazza. "I hear his words ringing through my ears every day of my life."

Spontaneous Music-Making

A typical school day for Ferrazza begins as early as 5:30 a.m., when he goes to the Kohl Building to practice. "I love the building and I love to be there. If I didn’t, I think I’d risk waking my family up and practice at home. Usually I’m the only one in the building except for the maintenance people; I’ve gotten to know them pretty well."

When Ferrazza began teaching at Oberlin, he didn’t even have an office; eventually he would be situated in a converted practice room in the Robertson Building, far from the department’s ad hoc center in Hales Gym. Today, with the entire program under one roof—"and a nice roof it is," says Dan Wall—the two see a discernible difference in the way they and their colleagues interact with one another as well as with students. "There’s no question about it," says Ferrazza. "Being closer to each other, things happen much faster now. We can even play together. There’s a better feeling all the way around."

If the members of the faculty gain from being right down the hall from one another, imagine the benefits that sort of access has upon the students. Conrad Reeves ’12, a jazz guitar performance major from Olmsted Falls, Ohio, studies with Ferrazza, whom he calls "an incredible teacher." Reeves believes that "the way that you get better at playing music with people is playing music with people, as much as possible. Here, we have the space where we’re able to do that at virtually any time of day, with any configuration of instruments, and with students who are so talented in so many different facets of jazz and improvised music. The amount of playing that I will have done here by the time I graduate is going to give me a big leg up in the professional world." In terms of raising his level of professionalism, Reeves says: "this is the most important thing that this building has done."

For Dan Wall, seeing students in the building’s computer lab, lobby, or rehearsal rooms "creates a unified feeling between us. It’s all been a real positive change." Ferrazza calls the Kohl Building "the most profoundly positive physical development—outside of faculty hires—that we’ve had in the department’s 23 years." He considers the building’s power to engender "spontaneous music making" to be one of his favorite aspects and tells a story to explain his point:

"One day, early in the fall semester, I had to leave to pick up some equipment we’d ordered from a music store. When I came back that evening, some of the students were outside in the courtyard, playing as they do every day when the weather is warm. As I was unloading the equipment, I noticed something different. A crowd of people had assembled around them. There were students I didn’t know, and people from the town, sitting on the benches in the courtyard. For our students to assemble an audience like this, in such an impromptu way, is absolutely fantastic. Many people—from the community, the administration, the alumni—have said that being able to see what our students are doing is one of the most remarkable things about the new building. It has its own energy about it."

This is exactly what the building’s designers were going for. In his architect’s statement about the Kohl Building, project designer Jonathan Kurtz, of the architectural and design firm Westlake Reed Leskosky (WRL), noted: "The Bertram and Judith Kohl Building heightens Oberlin’s visionary approach to education. It will make the conservatory education visible and provide new opportunities for the daily life of students. The goal is that the students, faculty, and community have a physical place of exchange; that the building and landscape generate unforeseeable interactions and elevate everyday experience."

Award-Winning Design

Anyone with a passing interest in Oberlin architecture knows that Minoru Yamasaki designed the conservatory in 1963, with iconic features that would later appear in his design for the World Trade Center. Paul Westlake, principal of WRL, says that the first question the architects and engineers at his Cleveland firm had to deal with in designing the Kohl Building was "how to do something that was as important as Yamasaki’s work without grafting a building onto it. We wanted to do something that respected it, maybe stood away from it, yet had its own identity and presence."

That presence is striking: Sheaths of custom-stained aluminum encase the building, and are married, handsomely, to gleaming walls of acoustically rated glass. The changeable play of light and shadow on the building gives it an almost Zelig-like aspect as its surfaces mirror the daytime sky: sometimes it’s pewter gray, sometimes it’s blue. Stull finds an analogy to music here.

"This building was designed to support great music, and when we think about music, it’s always reflecting back to us the essential nature of who we are," he says. "That’s a constantly changing dynamic. The building is able to reflect back to us, on a continuous basis, the changes of the natural world around us— even though it was built on a parking lot and is surrounded by hard structures—it takes on that glow no matter what time of day it is. The world around us is in a constant state of flux. That state of flux is exactly how we should think about music. That’s what we should love about it—it’s always about where we’re going."

Stull believes that the Kohl Building represents a vision for the future that "looks at the curriculum more broadly, and investigates how world music, classical, and jazz come together synergistically. How are we going to bring artists together from around the world? That is the question that continues to inspire us. This building, exceptional in every way, is an inspiration. But it can only reflect the inspiration of the people who are here."

For all the forward-looking and forward-thinking elements of the Kohl Building—Leon Dorsey calls it "100-percent high-tech in the most imaginative way"—one important characteristic found inspiration in Oberlin’s past. It was no arbitrary decision to make aluminum a predominant feature of the building; the material’s very DNA was forged at Oberlin. Charles Martin Hall, class of 1885, discovered the process for efficiently extracting aluminum oxide from bauxite while a chemistry student at Oberlin. Kurtz’s choice of material pays homage to that legacy. "The architectural team really liked the dialogue the material creates with the historical context of Oberlin," says Kurtz. He also loves the "geographic symmetry" of using a product "whose origins are really on the same city block."

Kurtz says that despite aluminum’s ubiquity as a building material, "it is physically almost nowhere to be found in Oberlin." The team used an entirely customized finish, which they produced in the lab with PPG Industries and Alcoa, the company founded by Hall in 1888.

Even before it was built, the Kohl Building began winning significant awards for its design team. [See sidebar.] The capstone, however, will be the environmental equivalent of a gold star. The Kohl Building is registered under the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) green building certification program, and the certification goal is LEED Gold. This was the architect’s intention from the beginning, and will mark the first time a facility exclusively dedicated to music would be gold-rated, a remarkable objective given the engineering innovation required to attain such a distinction while meeting the exacting acoustical standards of a music building.

Surround Sound and Boldface Names

Unlike Jake Silverman, Conrad Reeves, a junior, didn’t need to log on to the web to follow the Kohl Building’s progress; he watched it in real time, "stage by stage," from a Robertson Building practice room. He speaks enthusiastically about the new practice rooms that he gets to play in, with "state-of-the-art sound insulation. It’s hard to find a noise-free practice space where you can play at the volume you need to in order to work on your sound and hear only your instrument. It’s a thousand-fold better here than in Robertson, where I’d always be hearing a French horn or a bassoon or a vocalist."

He also appreciates the capability the rooms give him to record his practices. "It’s really great. There’s a unit in each of the rooms, like an equalizer or pre-amp, that’s attached to a CD player that connects to high-quality microphones hanging from the ceiling. You put a blank disc into the player, press a series of buttons, and it just records everything until you stop it. I perform in a duo with a trumpet player; we’ll record ourselves in these rooms and listen later. It’s so exposing; you can hear everything that you’re doing on your instrument. That’s been really valuable. It’s definitely improved my playing."

Last semester, as a member of the Oberlin Jazz Ensemble directed by Dennis Reynolds, Reeves practiced three times each week in the Joseph R. Clonick Recording Studio. "The lighting sets a really nice vibe," he says. "And it’s one of the most acoustically sound places they could make."

The building’s acoustics, and especially its recording studio, have already begun to attract professional musicians to Oberlin, but it was Stevie Wonder who baptized the studio with an impromptu concert. Dorsey and his wife, Chesley Maddox-Dorsey ’81, were instrumental in bringing their friend to campus for the dedication. The music legend spent 40 minutes playing the new Hamburg Steinway in the studio, giving a handful of fortunate onlookers the concert of a lifetime. "That’s how much he loved it," says Leon Dorsey. "He just sat there playing and lost track of time."

Now, says Stull, "some of the finest artists are recording here, including cellist Zuill Bailey and Tod Bowermaster, the third hornist of the St. Louis Symphony." Jake Silverman and his friends spotted one boldface name last semester: Japanese jazz pianist and composer Hiromi Uehara. "We saw her go into the recording studio. We heard that she was creating a final mix on one of her CDs."

They heard right.

Michael Bishop, a producer and engineer with Five/Four Productions, is preparing Hiromi’s newest CD, Voice, for a 2011 release on Telarc. He and his colleagues at Five/Four had initially learned about the Joseph Clonick Recording Studio in the Kohl Building through Dean Stull. They had also been involved in recording projects at Oberlin before, in Warner Concert Hall, so whenever Bishop visited campus, Director of Conservatory Audio Services Paul Eachus would walk him to the construction site and share the newest developments. Bishop liked what he was seeing: "We were anxious to give [the new recording studio] a try."

According to Bishop, "there’s really not a studio like it anywhere, where you have the combination of a great acoustic space with the particular equipment this control room has." The studio is rigged out with an analog mixer—a Rupert Neve Designs 5088—and a Sonoma DSD workstation, a Direct-Stream Digital recording system that samples audio 64 times that of standard CD resolution. Bishop says this set-up is unique among studios, although it is identical to the Sonoma DSD system that Five/Four employs. "There might be a couple of mastering rooms in L.A. that have this, but that’s about it."

Isn’t analog equipment something of a relic?

"It’s an attraction for us," says Bishop, who prefers analog to pulse-code modulation (PCM) digital. "We always work in analog at the front end of the recording chain up to the Sonoma DSD [direct-stream digital] recorder. This does sort of fly in the face of how studios are put together today, where everything is PCM digital. A PCM digital system ahead of the DSD system causes a bottleneck in the resolution that we try to keep throughout the recording process. An analog front-end retains the recording resolution all the way to the DSD recorder, where the signal is captured in the best possible form and resolution."

The acoustics and soundproofing also drew praise from Bishop. During the two intense 16-hour days that he had Hiromi in the control room for the final mix, the Oberlin Jazz Ensemble was rehearsing in the studio next door. "There was no sound interference at all," he says. "That’s a real testament to the quality of the design and construction of the building. We were not quiet, and they were not quiet, but no one knew the difference."

Bishop and his colleagues at Five/Four Productions definitely plan to use the studio for future projects.

Grammy Award-winner Esperanza Spalding shares her musical experience with Dean David H. Stull (at left) and jazz students in Clonick Studio in March 2011.

(Photo by Kevin Reeves)

As much as this pleases Stull—and it pleases him a great deal—he notes: "Our first priority is servicing the students and having this space available to all departments. When we think of Oberlin without this building, we think of how much we’ve not been able to do historically in its absence."

Stull illustrates his point by recounting a recent Warner Concert Hall performance by the Oberlin Contemporary Music Ensemble, conducted by Gardner Professor of Music Timothy Weiss and featuring Associate Professor of Clarinet Richard Hawkins as soloist, who performed Elliott Carter’s Clarinet Concerto. "Within a week following the concert, we moved into the Clonick Studio and did a full-blown recording session. Everything worked effortlessly. There were no sound interruptions," says Stull. "We now get to capture and preserve great performances, on an ongoing basis, which we know will represent Oberlin to the broader world. More importantly, we are able to simulate for our students the opportunity to work in a professional performance mode. We can give them a kind of confidence and set of skills that they didn’t have before, when this was not possible. Now it is."

Dan Wall teaches jazz improv in the recording studio, which has ample space for the 18 students in his class. "It’s a great-sounding room acoustically," he says. "Hearing such wonderful sound inspires the students—we’re all inspired by hearing ourselves when we’re playing with nice sound. This really helps us to relax and play better."

Kirkegaard Acoustic Design’s Dana Kirkegaard, who designed the acoustics and recording studio, would appreciate these endorsements.

It’s About the Music

Members of the Oberlin jazz faculty perform with music legend Stevie Wonder at the Kohl Building dedication

concert in May 2010.

(Photo by Kevin Reeves)

The recording studio is where jazz auditions are held for "fly-in" prospective students. "I always felt funny when visiting students auditioned in Hales," says Wall. "They see this great school with all of its wonderful facilities, but then we’d take them to Hales. This studio and the building give them a great impression of what the school is about."

Stull notes that although Oberlin has always had great applicants and students, the "application numbers have escalated dramatically" since the completion of the building. "There is a natural by-product of investing in a physical space that manifests what people can’t see," says Stull. "At the end of the day, this is the most important thing: quality must always be at the core. A building can limit that enterprise. A building alone cannot create that enterprise. But a building is an extension of something larger; it is emblematic of something you can’t see."

Tim Bennett, a fourth-year student from Chicago majoring in religion and jazz saxophone performance, works as a tour guide for the admissions office, so he is in part responsible for the impression that the jazz studies program makes on prospective students. "The main things I emphasize—and this has to do with me having been so close to Wendell—are the pictures of Hales that we have in the new building. I show them the development of going from the gym to the Kohl Building. I tell them that the building will be the first to be LEED-gold certified. I show them the rehearsal spaces, the recording studio."

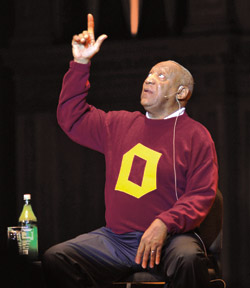

Celebrated actor and comedian Bill Cosby entertained the audience during opening festivities for the Kohl Building in May 2010. (Photo by Kevin Reeves)

Bennett studies with Visiting Professor of Jazz Saxophone Gary Bartz, who, he says, helped him to develop his own voice, compositionally as well as in performance. Bennett has had ample opportunity to experience what it’s like to play in the recording studio, both in Wall’s improv class and as a member of the Oberlin Jazz Ensemble. "It’s a great space to practice in," says Bennett. "A lot different than Hales Gym. Hales was a very small space, with no real central space for students to get together, and only three practice rooms."

Bennett is quick to point out, however, that Wendell Logan instilled his students with the belief that no matter how inadequate Hales Gym was, "it wasn’t really about where we were at, it was always more about the music, and what was going on inside the building. That’s something that’s transferred to the new building. We keep that as the heart of the program."

That said, Bennett appreciates the "real home" he and his fellow students now enjoy, and the easy access that he has not only to his teachers, but also to the conservatory at large. Faculty from the conservatory’s departments of music theory and music history, as well as some members of the music education faculty, also have offices in the Kohl Building. "There’s an improved sense of community," Bennett says. "It helps me interact with people better. I have all my resources in one place. That helps me a lot. I think it helps a lot of people."

Japanese jazz pianist and composer Hiromi Uehara (right) did a final mix of her latest CD in Clonick Studio with Michael Bishop of Five/Four Productions.

(Photo courtesy of Michael Bishop)

Bennett’s favorite space in the Kohl Building is the Sky Bar, for the expansive view it affords and for its flat-screen monitors, which stream images from two major collections that will ultimately be archived in the building—the Selch Collection of American Music History and the James and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection. Shipment of the latter, said to be the largest privately held collection of jazz recordings and memorabilia in the United States, began this summer. "Because of its mass, the shipments will happen over a long period of time," says Stull. "We’re beginning with the LPs, which number in the tens of thousands."

Bennett calls the Kohl Building "a very welcoming place to play. It’s a very polished building, and so you feel a little more professional. There’s a lot of prestige we feel with our playing. A lot more people are coming by—Dean Stull and other deans walk through the building," and, of course, prospective students.

Silverman, not all that far from having been a prospective student himself, will, by the time he graduates, have enjoyed the full benefit of beginning and ending his Oberlin music training in the Kohl Building. He already has his professional career mapped out: "After I complete my undergraduate studies at Oberlin, my plan is to get a doctoral degree in jazz studies. My dream job is to be a jazz studies professor at a university, to continue the tradition and the education of our country’s oldest form of music. I would love to teach at Oberlin. If it were available, I would take it in a heartbeat."

Marci Rich ’91 is president of KeyWord Communications LLC in Richmond, Virginia. She majored in English with a concentration in Creative Writing and is the former director of conservatory communications at Oberlin.

Oberlin College Bertram and Judith Kohl Building Awards

• 2011 Cleveland Engineering Society, Award of Excellence • 2010 AIA Western Mountain Region Design Award, Honor Award • 2010 AIA Ohio Design Award, Honor Award • 2010 AIA Cleveland Design Award, Honor Award • 2010 Lorain County Beautiful Award, Green Building Category • 2009 AIA Western Mountain Region Design Award, Honor Award for Unbuilt Work • 2007 AIA Ohio Design Award, Merit Award for Unbuilt Work • 2007 AIA Cleveland Design Award, Merit Award for Unbuilt Work

Oberlin would like to recognize the outstanding commitment made by the following donors to the Kohl Building. Their contributions and support were critical in creating this new and wonderful home for jazz.

- Stewart A. ‘77 & Donna M. Kohl

- James R. ‘58 & Susan Neumann

- Patricia Bakwin Selch

- Robert S. Lemle ‘75 & Roni Kohen-Lemle ‘76

- Joseph R. Clonick ‘57

- Peter & Karen Flint Family

- Paul ‘70 & Joan Schoenfeld

- Class of 1958

- Kutzen Family

- Motoko T. & Gordon L. Deane ‘71/’71

- Bert Ballin ‘43

- Class of 1960

- Joseph I. ‘65 & Phyllis B. Markoff

- Sarah Coade Mandell ‘87

- Frantz Ward LLP

- The Arent Charitable Foundation

- Clyde Smith McGregor ‘74

- Stephen A. ‘59 & Bonnie Ward Simon

- Margaret G. Papworth ‘41

- Kulas Foundation

- One Lucky Guy

- Clyde & Mary Lou Slicker ‘58/’58

- Harvey Culbert ‘58

- Leon L. Dorsey ‘81 & Chesley Y. Maddox-Dorsey ‘81

- Richard & Jean Rosaler Schram

Jazz Studies Faculty

- Gary Bartz

Visiting Professor of Jazz Saxophone - Marcus Belgrave

Professor Emeritus of Jazz Trumpet - Peter Dominguez

Professor of Jazz Studies and Double Bass - Robin Eubanks

Associate Professor of Jazz Trombone and Jazz Composition - Bobby Ferrazza

Director, Division of Jazz Studies and Associate Professor of Jazz Guitar - Billy Hart

Associate Professor of Jazz Percussion - Sean Jones

Assistant Professor of Jazz Trumpet - Dan Wall

Associate Professor of Jazz Piano

It takes a diverse array of ideas, plans, projects, and materials to construct a facility as extraordinary as the Bertram and Judith Kohl Building, with a foundation formed by the magical fusion of an equally diverse array of inspired, dedicated, and generous people. "This building came about because of a great team," says Dean of the Conservatory David H. Stull. "It was a combination of this particular collection of donors, conjunctive with this faculty, this program, these architects, and this institutional leadership. There is no question: it was the team that got us here. I cannot imagine removing any single one of those elements and getting this result." Here are profiles of the four lead donors for the project. Additional information, including biographies of the members of Oberlin’s jazz studies faculty, the Kohl Building’s architects, and Oberlin’s leadership, can be found in the press room on the Oberlin website [www.oberlin.edu/kohl/news.html].

Yiddish Words for $5 Million: What is Nachas?

Joseph Clonick ’57 gives an impromptu performance in the recording studio that bears his name.

(Photo courtesy of Dana KirkegaArd)

The proud pleasure one derives from one’s children or grandchildren, called nachas in Yiddish, is one of the reasons why Joseph Clonick ’57 contributed $5 million to fund the recording studio that bears his name in the Kohl Building. "I don’t have children or grandchildren to give me nachas," he says. Oberlin’s jazz studies students, with their varied accomplishments, will, therefore, give Clonick that wonderful feeling by proxy.

There’s another definition of nachas, Clonick says: "The gratification you get when your gift is being used in a way that makes you happy."

Joe Clonick is a very happy man. And music, as much as nachas, has had something to do with that.

The Chicago native majored in composition at Oberlin, studying with Professor of Music Composition and Theory Joseph Wood. But Clonick ultimately focused his career as a pianist on what he calls his "true love" in music, a genre for which there are not many outlets: "I carved out my tiny niche in classical improvisation."

"You sort of have to make believers out of the listeners," he says. "My approach to classical improv is that the music be totally spontaneous." As a student he hosted a program on WOBC in which he’d invite listeners to phone in and provide him with a theme to kindle his "improvisatory ventures."

And although classical improvisation is foremost among his interests, he has been known to cross over. In Chicago, Clonick spent five years in the early 1960s as musical director and pianist at the Happy Medium, a cabaret theater. His next gig was as house pianist for the famed London House—"the finest jazz room at the time." Clonick took the stage when the featured acts (André Previn, for example) took their breaks. He calls Previn his "hero" for his success transcending all musical genres.

"The London House was a tight space, and my group was small—just me on piano, a bass player, and a drummer. We’d improvise, maybe playing something new that sounded like an old standard. The diners squeezed their way through the tables to come up to me on the bandstand, puzzled, to ask where the dance floor was. I wasn’t playing dance music, of course. This just gives you a clue that I was not your ordinary jazz pianist."

Clonick left Chicago in 1969 for New York City, and an entirely new musical adventure. After auditioning to win a coveted spot in the BMI Lehman Engel Musical Theater Workshop, sort of an Actors’ Studio for composers, Clonick became a fixture there and an Engel protégé—the director was considered one of the preeminent Broadway conductors in the 1940s and 1950s. Fellow students included Ed Kleban, the future lyricist for A Chorus Line, and Melanie Chartoff, who became an important collaborator. It was a nurturing and productive time, and Clonick wrote many shows, among them Scrooge: A Christmas Ghost Story, with lyricist Nancy Leeds. Clonick met one of his greatest friends and writing partners, Ralph Chicorel, when the latter poked around the edges of the workshop.

While living in New York, Clonick found time to pursue a different kind of composing; he created crossword puzzles for the New York Times. An avid puzzle aficionado, he was a regular at the American Crosswords Puzzle Tournaments, and once finished third.

It’s not a great leap from crosswords to trivia, and in 1994 Clonick parlayed his considerable talents into a four-program stint on the quiz show Jeopardy.

Now semi-retired and back in Chicago, Clonick plays piano once a month for the homeless at his synagogue’s soup kitchen in Evanston. "They’re the most receptive audience I ever had."

You could say that their delight in his performances gives Clonick nachas. - MR

Family Values

Major donors of the Kohl Building at the groundbreaking ceremony in June 2008. (L to R): Joseph Clonick ’57, Clyde McGregor ’74, and James Neumann ’58.

(Photo courtesy of Kevin Reeves)

Clyde McGregor ’74 of Chicago manages more than $25 billion in assets as a partner at Harris Associates and as co-manager of the Oakmark Equity and Income Fund and the Oakmark Global Fund. Suffice to say he’s familiar with the value of things—not least of which is the value of hard work and lessons learned in hard times.

His mother, Lilly, an only child who grew up during the Great Depression, was able to attend Oberlin in part because the advent of World War II revived her father’s steel supply business. She graduated with degrees in English and organ performance and worked primarily as a music teacher, church organist, and choir director. A single mother, Lilly raised Clyde in Pittsburgh with the help of her parents.

At Oberlin, McGregor majored in religion and economics, supplementing his financial aid package with "the best student job on campus—running the linen service." His off-campus jobs were decidedly less glamorous. He worked two summers as a gandy dancer, repairing tracks for the Pittsburgh-Allegheny-McKees Rocks Railroad; he was a ground man on an overhead crane crew; he made paint in a paint factory; and he washed dishes in a hospital kitchen.

After graduation, having studied welfare policy with Professor of Economics Hirschel Kasper, McGregor was preparing to leave for Washington, D.C., and a job with the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. But in one of Richard Nixon’s last official acts before resigning the presidency, he eliminated the position. With the 1974 recession taking hold, McGregor scrambled from one uninteresting job to another until an unexpected door opened: a scholarship to attend business school.

The late Lilly Marie Smith McGregor ’43, namesake of the Kohl Building’s Sky Bar. (Photo courtesy of Kevin Reeves)

As an Obie who came of age in the early 1970s, he says that he "viewed this as a sellout of my values. But I was out of money. I was selling calculators in a department store, wondering how I was going to be able to afford a graduate program in public policy." He relented and earned an MBA in finance at the University of Wisconsin, a path that changed not only his life, but also his financial circumstances.

He life has, he says, been blessed in numerous ways. And if he has a philosophy of philanthropy, it is this: "I never want my assets to control me. If I can give them away freely, I know that I have exercised control. Having spent 34 years of my career dealing with other people’s wealth in the abstract, I always try to have an appropriate perspective. Wealth is a means to an end; I strive to ensure that the ends to which I apply my wealth are ones that make me proud."

McGregor’s $4 million gift to Oberlin in support of the Kohl Building fulfills that objective. "This is a place that greatly helped me evolve and move forward as a human being, and changed my life," says McGregor, who is also a member and chair-elect of Oberlin College’s Board of Trustees. The gift, appropriately, honors his mother, who in her Oberlin years was known as Lilly Marie. Visitors to the third-floor lounge can see her name on the wall of what is known informally as the Sky Bar.

What would Lilly McGregor have to say about all of this?

"My mother could sit down at a piano and play 800 things without really thinking about it, and beat out jazz numbers from the 1930s and 1940s—that era was her sweet spot. But she was not what you would call a jazz aficionado. She would think it hysterically funny to have her name on part of a jazz building in a flying lounge. And she would be pleasantly surprised to learn that her son had been able to make such a gift."

Lilly Marie Smith McGregor ’43 died in 1996. - MR

Metaphors of Collaboration

Robert Lemle ’75 and Roni Kohen-Lemle ’76 at the Kohl Building

dedication weekend.

(Photo courtesy of Kevin Reeves)

Robert Lemle ’75 enjoys a birds-eye view of Oberlin. Not only has he served on the Board of Trustees for 15 years (as chair for the last six, as acting chair for the two before that), he is also married to and the father of alumnae: Roni Kohen-Lemle ’76 and Joanna Lemle ’10, respectively. It will be alums, he says, who will determine whether or not Oberlin will have the financial resources to sustain its potent combination of academic, artistic, and musical excellence.

To the extent that Lemle believes one should lead by example, he and his wife contributed a substantial gift in support of the Kohl Building. He views the building as more metaphor than matrix, and describes the "Aha!" moment he experienced during the dedication weekend:

"When I saw the excitement, energy, and good will of the people who came together to celebrate the building’s opening and to celebrate Wendell Logan—alumni, Stevie Wonder, Bill and Camille Cosby—I began to appreciate the significance of the building beyond the thing itself," he says. "It literally embodies the idea that music is central to life at Oberlin, and it has tremendous potential to build community. One of the most meaningful things I came to appreciate that weekend was the connection between this building—dedicated to our country’s great African American music—and Oberlin’s role in African American history."

Not surprisingly, Lemle’s preferred space in the building is the approach to the building, the entry plaza: "It is my favorite because it is designed to welcome us all. It is a metaphor for connection and collaboration, not only among all aspects of Oberlin’s music program, but also between the college and the conservatory, and with the town."

The idea of collaboration comes up frequently when speaking with Robert Lemle.

"To create a great building, you need to start with talented people—a David Stull, a Jonathan Kurtz and Paul Westlake, a Wendell Logan, so many others—who possess a tremendous level of commitment. That, and a thoughtful, open process, will determine the outcome. The process for designing the building, and the skill and enthusiasm of those involved, gave me a lot of confidence in the outcome."

Lemle says he is particularly excited by the "unexpected" in the "first new Oberlin building of the 21st century: What collaborations will come out of it? What opportunities will it create for Oberlin’s academic, artistic, and musical offerings? One of my greatest hopes for the building—that it attracts outstanding talent to Oberlin—is already happening." The Office of Conservatory Admissions reports that applications for the jazz studies major are up a significant percent from the previous admissions cycle. And the numbers have been trending upward for the last five years, around the time when the building project was first announced.

A native New Yorker, Lemle majored in government at Oberlin. He and Roni met as students; she was a studio art and art history major. Lemle went on to earn a law degree at New York University, and, after a career rich with leadership roles, retired as vice chairman and general counsel for Cablevisions System Corporation. He now spends his time championing not only Oberlin, but also the Long Island Children’s Museum, which he and Roni founded in 1989 with several other parents.

Music, he adds, is also an important part of his family’s life.

Both Roni and Joanna Lemle are jazz singers. When Joanna presented her senior recital in the Cat in the Cream in May of 2010, her mother joined her onstage for a rendition of Ray Charles’ "Midnight." Her father was in the audience, watching—and taking delight in—the collaboration. - MR