History 912: Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge

[NOTE: This is the course syllabus as of July 30, 1999. The final syllabus could be somewhat different and will include weekly assignments]

There are a huge number of museums in Great Britain. Many of them have their own web sites, some of which are more useful than others. Most, however, do provide essential information (location, directions, opening hours, fees, nature of collections, special exhibits, etc.), and so a consultation on the Internet can save you some time. The best starting point is Museums Around the UK on the Web which provides an alphabetical listing of hundreds of museums.

September 15: "The Primary Function of Any Museum Is…" Introduction. What is a Museum?

What is a museum? What is fitting to "put" in a museum? Why does one put things in a museum? Why does one go to museums? In this opening section, we will explore the idea of a museum via the students' experiences and some reading. Are the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum and your collection of "Frutopia" labels both museums exhibits? Are there differences between "collections" and "museums"? Why are some objects curated by a Department of Prints and Drawing at one museum whereas it will be farmed out to the Department of Antiquities in another? What have you liked about museums and what not? What is, after all is said and done, the "museum experience?" British Lawnmower Museum

British Lawnmower Museum

Readings:

James A. Boon, "Why Museums Make Me Sad," in Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures. The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display (Washington and London: Smithsonian Press, 1991), pp. 255-277. [NOTE: This is a good essay to read both at the beginning and the ending of the course. In its style, almost more than in its content, it mimics the museum and the process of museum going. Read it first, without stopping to "figure everything out." Then return to it at the end of the course and see what you make of it.

Sharon Macdonald, "Introduction," in Theorizing Museums. Representing Identity and Diversity in a Changing World, ed. Sharon Macdonald and Gordon Fyfe (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996), pp. 1-18.

Carol Duncan, "The Museum as Ritual," in Civilizing Rituals. Inside Public Art Museums (London and NY: Routledge, 1995), pp. 7-20. [Course Pack: Note - There will be one "Course Pack" per flat in London]

D.H. Lawrence, "Things," The Complete Short Stories, Vol. III (London: Heinemann, 1955), pp. 844-853. [Course Pack]

John Berger, Ways of Seeing (Penguin), 1972, Chapter 1. [Note: Although this is not a course in "art appreciation," museums are fundamentally visual spaces composed of concrete images. Berger's perceptive work, which many of you have probably already read, can introduce you to some of ways in which visual information is sent and received. You can read the entire book at the start of the course or just read the chapters as they are assigned. I do recommend reading the whole book before you spend a lot of time in art museums, in particular.]

Museum Visit: Your choice. Questionnaire will be handed out.

September 22: Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. The Origin and Organization of Museums prior to Modernity.

How do we understand the impetus to collect and the consequent/subsequent organization of museum collections? Pearce explores the various impulses behind collecting (leading to different types of museums or collections) and offers a brief overview of the history of museum collections. Using Michel Foucault's Order of Things as a theoretical framework for her argument, Hooper-Greenhill examines the ways in which the museum's logic reflects the "structure" of knowledge at different epistemic moments. The Borges introduction is pure Borges -- a lovely piece of intellectual trivia that inspired Foucault and should lead you to question what it is that allows us to gather certain items together in a collection.Readings:

Jorge Luis Borges, "The Analytical Language of John Wilkins," in Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952, trans. Ruth L.C. Simms (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1964), pp. 101-105. [Course Pack]

Susan M. Pearce, "Collecting: Shaping the World," in Museums, Objects, and Collections: A Cultural Study (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 1992), pp. 68-88, and "Museums, the Intellectual Rationale," (pp. 89-117). [Course Pack]

Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, "What is a Museum?" in Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge (London and New York: Routledge, 1992), 1-22. [Course Pack]

Optional Readings:

On the studiolo: Olga Raggio and Antoine M. Wilmering, The Liberal Arts Studiolo from the Ducal Palace at Gubbio (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art), 1996.

On "curiosity cabinets," particularly of a contemporary variety: Lawrence Weschler, Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder. Pronged Ants, Horned Humans, Mice on Toast, and Other Marvels of Jurassic Technology (New York: Pantheon), 1995.

On the historical contextualization of museums using Foucault's epistemes as an organizing principle: Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge (London and New York: Routledge), 1992. [Chapters include: The First Museum of Europe (Medici Palace); The Palace of the Prince; The Irrational Cabinet; The "Cabinet of the World" (the "studiolo"); The Repository of the Royal Society (classical); and the Disciplinary Museum.]

For Hooper-Greenhill's main theoretical inspiration, Michel Foucault, The Order of Things. An Archaeology of the Human Sciences [originally Les Mots et les choses] (New York: Vintage), 1994 [1966].

Those interested in one interpretation of the phenomenon of collecting itself would do well to read Jean Baudrillard, The System of Objects, trans. James Benedict (London and New York: Verso), 1996, especially "Marginal Objects: Antiques" (pp. 73-84) and "A Marginal System: Collecting" (pp. 85-106).

Arjun Appadurai, ed., The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1986.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Eugene Rochberg-Halton, The Meaning of Things (Cambridge), 1981.

Dulwich Picture Gallery

Museum Visit: Visit to one of the older London museums to be arranged. Possibilities include the Bethnal Green Museum of Childhood (a modern collection, but housed in one of Great Britain's oldest wrought iron buildings); the Cuming Museum (aka Museum of Southwark's History), which is a good example of a "collection" rather than a "museum;" the Dulwich Picture Gallery (designed by Sir John Soane and opened in 1817, represents a literal merging of mausoleum -- which contains the bodies of the family which commissioned the collection -- and modern art museum; or Sir John Soane's Museum (the architect of the Dulwich, the Bank of England, and other notable structures, the museum is his old house on Lincoln Inn Fields.

September 29: Museums and Modernity. The History of Museums and Their Particular Political Function with the Advent of Modernity and the Public Sphere.

In this section we will explore the relationship of the museum to modernity - in particular we want to explore the relationship of museums to the notion of public space, both its historical creation and its specific location in late-18th and 19th century. We will focus on department stores, the press, fairs, and circuses. We also want to examine the promise of museums as related to their location in political modernity: democratic representation (both in the museum and in terms of museum goers). The readings set out the them first theoretically (Habermas) - and you are encouraged to read that first - and then historically (Duncan, Georgel). Both Bennett and Koven demonstrate the way in which the "democratic" culture of the museum as public space was opened to the working class (in controlled ways, to be sure), whereas Ames notes that this was, at best, a highly contested process.Readings:

Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, trans. Thomas Burger (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991 [1962]), pp. 27-51, 57-67. [Course Pack]

Carol Duncan, "From the Princely Gallery to the Public Art Museum. The Louvre Museum and the National Gallery, London," in Civilizing Rituals, pp. 21-47. [Course Pack]

Chantal Georgel, "The Museum as Metaphor in Nineteenth-Century France," in Daniel J. Sherman and Irit Rogoff, eds., Museum Culture. Histories, Discourses, Spectacles (London: Routledge, 1994), pp. 113-122.

Tony Bennett, "Speaking to the Eyes: Museums, Legibility and the Social Order," in Sharon MacDonald, ed., The Politics of Display. Museums, Science, Culture (London: Routledge, 1998), pp. 25-35.

Seth Koven, "The Whitechapel Picture Exhibitions and the Politics of Seeing," in Sherman and Rogoff, eds., Museum Culture, pp. 22-48.

Michael M. Ames, "The Development of Museums in the Western World: Tensions between Democratization and Professionalization," in Cannibal Tours and Glass Boxes. The Anthropology of Museums (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1992), pp. 15-24. [Course Pack]

Museum Visit: Harrods (yes, Harrods, the department store)

October 6: Museum Design: Ways of Narrating, Ways of Seeing.

Two main issues need to be discussed in this section, both of which build off the idea of the museum as a product of modernity: (1) The idea of the museum as a narrative structure. (Roberts) Much like a novel (itself a 19th century phenomenon) or a nation, the museum is a narrative structure which is fundamentally implicated in interpretation. (2) The design and space of the (modern) museum is bound up with its existence as a public space. (Bennett) In that sense it is expected to be open to publics at the same time that it is concerned both with how the publics will behave in museums and how they will use the museum. We will explore these issues in terms of the design of the interior museum space (rather than its external architecture), and as relates to the transmission of certain "privileged" forms of knowledge, science (Macdonald)Readings:

Svetlana Alpers, "The Museum as a Way of Seeing," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 25-32.

Tony Bennett, "Museums and Progress. Narrative, Ideology, Performance," in The Birth of the Museum. History, Theory, Politics (London and NY: Routledge, 1995), pp. 177-209. [Course Pack]

Lisa C. Roberts, From Knowledge to Narrative. Educators and the Changing Museum (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997), pp. 56-67, 131-150. [Course Pack]

Susan M. Pearce, "Meaningful Exhibition: Knowledge Displayed," in Museums, Objects, and Collections, pp. 136-143. [Course Pack]

Sharon Macdonald, "Exhibitions of Power and Powers of Exhibition. An Introduction to the Politics of Display," in MacDonald, ed., The Politics of Display, pp. 1-17 (only).

Museum Visit: The "Hall of Birds" and the Human Biology displays in the Natural History Museum.

October 13: Museums, Capitalism, and the National Project. "Art, to be interesting, must be national." (Sir William Armstrong, National Gallery of Ireland)

Nations, like museums, are constructs whose identity is historically narrated. In this section we want to explore the meaning behind that by looking at three important "national" museums: the Louvre in France, and the National Gallery and the Tate in Britain. As "national" museums (the Tate being a museum specifically devoted to British art), we want to understand what it means to have "national" art (for example, as the Bennett article will stress, there has been a certain amount of controversy as to whether "British art" consists of art created by British citizens or is rather any art hung in a British collection (treasures, as it were, of British acquisition and/or conquest). But we want to explore the relationship between the national museum and the creation of national identity via the museum. Duncan-Wallach, Sherman, and Bennett present arguments on whether museums are locations where the (national) canon is passed on to a broader public (i.e., where hegemony is extended) or whether they are sites where hegemony is contested, where conflict is present. The first three articles listed should be read in the order given since the chronology of their writing is quite important to keep in mind (and because they refer back to the previous articles).Museums, of course, also can enact the nation as empire (and London as the heart of that empire). Barringer's brief piece on the "South Kensington Museum" suggests the way in which that it accomplished.

Readings:

Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach, "The Universal Survey Museum," Art History 3:4 (December 1980): 448-469. [Course Pack]

Daniel J. Sherman, "The Bourgeoisie, Cultural Appropriation, and the Art Museum in Nineteenth Century France," Radical History Review 38 (1987): 38-58. [Course Pack]

Gordon Fyfe, "A Trojan Horse at the Tate: Theorizing the Museum as Agency and Structure," in Macdonald and Fyfe, Theorizing Museums, pp. 203-228.

Tim Barringer, "The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project," in Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn, eds., Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum (London and New York: Routledge1998), pp. 11-27. [Course Pack]

After reading the set of three articles (the inter-textual discussion on the relationship between capitalism, ideology, and nation), and the Barringer article, please turn to:

John Berger, Ways of Seeing (Penguin), 1972, Chapter 5.

Optional Reading:

Nicholas Pearson, The State and the Visual Arts (Milton Keynes, England: The Open University Press), 1982.

Janet Minihan, The Nationalization of Culture: The Development of State Subsidies to the Arts in Great Britain (New York: New York University Press), 1977.

Detlef Hoffmann, "The German Art Museum and the History of the Nation," in Sherman and Rogoff, eds., Museum Culture, pp. 3-21.

Museum Visit: Visit in pairs or threes to either the Tate, the National Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery, or the British Museum (your choice).

October 20: Material Culture and the Production of Historical Narratives. Artifacts and Authenticity.

In general, the objects preserved in museums are both solid (i.e., three dimensional) and come from out of the past, so that the observer experiencing them in three-dimensional space must somehow also cross a barrier of change in time. In this sense alone, then, museums are not the same as, say, illustrated books. But if we recognize this difference, we also need to raise some basic questions about how museums (fundamentally non-art museums, in this context) work. The questions we confront have to do with what is "real," what is "authentic" (and, in that sense, we can also be dealing with art and the question of forgeries), and how we relate to "old" three-dimensional objects. Do objects have meaning sui generis? What role do museums have in terms of mediating experiences? In this week, we the explore the relationship of material culture (the artifact) to "truth," "reality," or "authenticity," and the specific set of questions which are raised for institutions which choose to preserve and promote material culture.The readings all involve objects (artifacts) and their meanings - the relationship between artifact and meaning. Some (Radley) treat the way in which we perceive objects in a social psychological way; some pose the way in which artifacts produce either "resonance" or "wonder" in the viewer (Greenblatt); and some treat the issue of how artifacts change their meaning depending on where they are situated (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett). Both Crew and Sims and Pearce suggest how historical study gives meaning to material culture and how our possession of objects for the human past influences the way in which we understand the past. The Mamet script is a playful approach to all the questions of "reality" within a museum context.

Reading:

Alan Radley, "Boredom, Fascination and Mortality: Reflections Upon the Experience of Museum Visiting," in Gaynor Kavanagh, ed., Museum Languages: Objects and Texts (Leicester, London and NY: Leicester University Press, 1991), pp. 65-82. [Course Pack]

Stephen Greenblatt, "Resonance and Wonder," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 42-56.

Spencer R. Crew and James E. Sims, "Locating Authenticity: Fragments of a Dialogue," in Karp Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 159-175.

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, "Objects of Ethnography," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 386-393 (only).

Susan M. Pearce, "Meaning in History," in Museum, Object, and Collection, pp. 192-209. [Course Pack]

David Mamet, "The Museum of Science and Industry Story," in Five Television Plays (New York Grove Weidenfeld, 1990), pp. 91-125. [Course Pack]

Optional Reading:

P. Connerton, How Societies Remember (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1989.

David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1985.

Flora E.S. Kaplan, ed., Museums and the Making of "Ourselves". The Role of Objects in National Identity (London and New York: Leicester University Press), 1994.

Museum Visit: The Elgin Marbles in the British Museum

November 3: Whose Heritage? History and the Diverse Community.

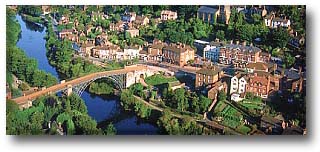

Ironbridge Gorge Museum

Ironbridge Gorge Museum

The focus in this section is on the issue of "heritage," both the obvious question of whose history is represented, whose heritage is included and whose excluded, but also the question of the "heritage industry" in general what "heritage sites" are intended to make us feel. We will examine questions of "reality," "imitation," and "authenticity" as they relate to "heritage" and cultural desires (Roberts), the production of nostalgia and memory at heritage sites (Urry), and how less-powerful nations attempt to project "their" heritage and the confusions which arise when manipulating essentialist categories (Handler). Finally, West explores the struggle to provide historical representation to the working class and Simpson studies the creation of Liverpool's Transatlantic Slavery Museum as a forum to give representation to Britain's Black community. This last piece, in particular, will give us a sense of some of the difficulties of representing specific minority racial or ethnic "presences" in a broader national culture. We will visit the museum as well as two other "heritage" sites in the same location: the Merseyside Museum of Labour History and the Albert Dock.

Readings:

Richard Handler, "On Having a Culture: Nationalism and the Preservation of Quebec's Patrimoine," in George W. Stocking, Jr., ed., Objects and Others. Essays on Museums and Material Culture (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), pp. 192-217.[Course Pack]

John Urry, "How Societies Remember the Past," in Macdonald and Fyfe, Theorizing Museums, pp.45-65. [Course Pack]

Lisa C. Roberts, From Knowledge to Narrative, pp. 88-103. [Course Pack]

Bob West, "The Making of the English Working Past: A Critical View of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum," in Robert Lumley, ed., The Museum Time-Machine. Putting Cultures on Display (London and NY: Comedia/Routledge, 1988), pp. 36-62. [Course Pack]

Moira G. Simpson, "History Revisited," in Making Representations: Museums in the Post-Colonial Era (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), pp. 15-49. [NOTE: This is in the Course Pack for the Joint Course]

Paul Gilroy, "This Island Race," The New Statesman & Society (2 February 1990), pp. 30-32. [Joint Course Course Pack]

John Berger, Ways of Seeing (Penguin), 1972, Chapter 6.

Optional Readings:

Miles Orvell, The Real Thing: Imitation and Authenticity in American Culture, 1880-1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 1989.

Dean MacCannell, The Tourist. A New Theory of the Leisure Class (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press), 1999.

Umberto Eco, Travels in Hyperreality: Essays (San Diego: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich), 1986.

Jean Baudrillard, The System of Objects, trans. James Benedict (London and New York: Verso), 1996.

Museum Visit: Visit to Liverpool's Transatlantic Slavery Museum and discussion with one of its original curators, Ross Dawson. If time permits, also visit Merseyside Museum of Labour History and the Albert Dock.

November 10: History vs. Memory. The Enola Gay Controversy at the Smithsonian.

The authority of museums to create interpretations is challenged today as never before by both the visiting public and museum professionals. Because museums are central public institutions that mediate culture for growing numbers of people, they have become ground zero in the "culture wars" being waged in many countries, particularly the United States and, to a certain extent, Britain. Museum curators, museologists, and students of museum practice now read the names of specific exhibits as if they were battles sites from a war: Harlem on My Mind (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1969), The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820-1920 (National Museum of American Art, 1991); Sigmund Freud: Conflict and Culture (Library of Congress, 1998), Birth and Breeding: the Politics of Reproduction in Modern Britain (Wellcome Institute, 1993-4). For most observers, the most explosive battle of this war was the Enola Gay exhibit (originally titled The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb and the Origins of the Cold War) that was to open at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum in the mid-1990s. All our readings this week concern this exhibit, and we will want to examine a number of issues. Why are museums becoming such critical spaces for "culture wars"? What are the museum's obligations of interpretation or, as one curator puts it: "Why not take sides? Why not be partial? How can we possibly understand the issues involved, when the whole point of history is being systematically denied?" A reasonable assessment, but how does this play out at publicly funded museums, particularly those thought to be representative of the "nation" as a whole? How can museum curators prepare their defenses for seemingly inevitable attacks?Readings:

Thomas F. Gieryn, "Balancing Acts. Science, Enola Gay and History Wars at the Smithsonian," in Macdonald, ed., The Politics of Display, pp. 197-228.

Edward T. Linenthal, "Anatomy of a Controversy," in Edward T. Linenthal and Tom Engelhardt, History Wars. The Enola Gay and Other Battles for the American Past (NY: Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt & Co., 1996), pp. 9-62.

Mike Wallace, "Culture War, History Front," in Linenthal and Engelhardt, History Wars, pp. 187-198.

Lisa C. Roberts, From Knowledge to Narrative, pp. 72-79. [Course Pack]

Optional Reading:

Steven C. Dublin, Displays of Power. Memory and Amnesia in the American Museum (New York: New York University Press), 1999.

Other essays in Edward T. Linenthal and Tom Engelhardt, History Wars, 1996.

Vera Zolberg, "Museums as Contestec Sites of Remembrance: the Enola Gay Affair," in Macdonald and Fyfe, eds., Theorizing Museums, pp. 69-82.

Museum Visit: Museum visit optional this week, but you should be on the lookout for any current exhibit that has become "controversial" in London.

November 17: Museums and the International Political and Economic Order. World's Fairs and International Expositions.

The development of the (modern) museum, as we have seen, is intimately linked with the creation of the nation-state. This has ramifications not just for the way in which the constructed nation is represented within a museum context (e.g. who is included and who left out, as in the November 3rd readings), but also on the ways in which nations compete politically and economically in the international arena. We have already examined this competition in the context of the so-called "universal survey museums" (e.g. the October 13th readings concerning the Louvre, the National Gallery, the British Museum, etc.). Simply put, if France has an Egyptian collection, Britain must, as well. The ability to mount such "universal" collections, of course, is also tied to the expansion of imperialism in these countries, a process which we will further explore when we examine the construction of museums of the ethnology.Here, we want to look at the ways in which nations compete with each other via the medium of world's fairs and other international expositions. The first of these was the Great International Exposition mounted at the Crystal Palace in London. Among subsequent fairs were those in New York in 1853; the (U.S.) Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876; the Paris Exposition of 1889; the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, 1893 (Hinsley), and the Great Exhibition of Paris (1900), St. Louis (1904), and London (1908). The tradition has continued to the present time with such modern fairs as the Seville Expo'92 (Harvey), and, of course, the hugely expensive Millennium Dome in Greenwich (England), slated to open on January 1, 2000. Besides examining this international competition, we will also explore ways in which nations "sell" themselves abroad via the vehicle of the "blockbuster" exhibition on loan (Wallis). Finally, we will look at how and why "peripheral" countries (i.e. countries subject to imperialist intervention) attempted to use World's Fairs to project themselves into modernity and the international market (Tenorio-Trillo).

Readings:

Curtis M. Hinsley, "The World as Marketplace: Commodification of the Exotic at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp.344-365.

Penelope Harvey, "Nations on Display. Technology and Culture in Expo '92," in Macdonald, ed., The Politics of Display, pp. 139-158.

Brian Wallis, "Selling Nations: International Exhibitions and Cultural Diplomacy," in Sherman and Rogoff, eds., Museum Culture, pp. 265-281.

Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo, Mexico at the World's Fairs. Crafting a Modern Nation (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996), pps. 15-47, 55-63. (Those interested in following the problematic attempt of Mexico's national construction at the Paris Fair and later are encouraged to read the entire book.) [Course Pack]

Optional Reading:

Tenorio-Trillo, Mexico at the World's Fairs, 1996.

Erik Mattie, World's Fairs (New York: Princeton Architectural Press), 1998.

World's Fairs and expositions between 1851-1916

For some outstanding information on the U.S. in World's Fairs and Expositions during the same time period: World's Fairs and Expositions: Defining America and the World, 1876-1916. Part of the site is devoted to African Americans at World's Fairs and Expositions.

Museum Visit: We will attempt to see whether we can follow up on the preparation of the Millennium Dome in Greenwich, although the Dome itself does not open until January 1, 2000. As a beginning, you can access the Dome's web site ("The Dome is a beacon for all our futures").

November 24: Museums and the Ethnographic Other.

If international exhibitions and world's fairs allow nations to establish their pedigrees and compete for trade and power, museums (and local fairs) allow museum organizers to establish a sense of the "national" by virtue of their representation of the colonial, the "folk," or the otherwise ethnographic Other. In the week of October 13, we examined the importance of the "national" museum and its power as a site of (perhaps contested) ideological messages. Here we look at the importance of the museum in the creation of the national and the Other.The question to be examined is how a particular artifact/people/culture/time is becomes available to an unfamiliar people. The exoticization of the unfamiliar (i.e., its separation from a presumed familiar) is often mediated by specific ideological institutions among which museums are central. We will first approach this issue through an uncommon route, an examination of the way in which "Assyria" was made available to the mid-19th century British via a series of institutions: the British Museum, the Illustrated London News, and popular theater. In the words of Bohrer, we will be "tracking a sign through the inflection of its signifiers." This can give an appreciation both for the locations of "exoticness" (temporal as well as spatial difference), the ways in which a public can contest elite aesthetic notions, and the specific role of the museum in introducing the "other" into a presumed homogeneous British public.

While Bohrer traces this creation of difference via artifacts, Coombes examines this process with people and cultures. At the same time that the British are mounting a major in international fairs and exhibitions, they are grappling with the construction of some of the major ethnographic museum collections at home, the famous Pitt River collection in Oxford (unfortunately closed throughout 1999), the Horniman Museum, and others. These collections and others will help forge a "national" subject by insist on the relationship between race and culture, and stressing their educational role among the masses. At the same time, we can see the discourses of national identity, gender, imperialism, and anthropology coming together in the early 20th century at the Franco-British Exhibition in London (1908). This provides an important site in which we can chart the formation of a national identity and culture and the concomitant marginalization of the Irish and other non-English cultures as "folk" cultures available for inspection just as Somalis or Senegalese.

Finally, Clunas discusses the way in which "China" was made available to Britain in the 19th and 20th centuries, and as a reflection of British imperial rise and decline.

Reading (together with Joint Class):

Frederick N. Bohrer, "The Times and Spaces of History: Representation, Assyria, and the British Museum," in Sherman and Rogoff, eds., Museum Culture, pp. 197-222.

Annie E. Coombes, "Temples of Empire: The Museum and its Publics," and "National Unity and Racial and Ethnic Identities: The Franco-British Exhibition of 1908," in Reinventing Africa. Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994), pp. 109-128; 187-213. [NOTE: Copy in the Course Pack for the Joint Course]

Craig Clunas, "China in Britain. The Imperial Collections," in Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn, eds., Colonialism and the Object. Empire, Material Culture, and the Museum (London and New York: Routledge, 1998), pp. 41-51. [Joint Course Course Pack]

Optional Readings:

Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn, eds., Colonialism and the Object. Empire, Material Culture, and the Museum (London and New York: Routledge), 1998.

Museum Visits: Horniman Museum and the Assyrian sculptures in the British Museum. We might also try to get to the Ashmolean in Oxford.

December 1: Constituting Difference Visually. New Museum Practices.

We have focused repeatedly on the visual nature of the museum. In this section, we concentrate on how difference is constituted visually in museums. All three articles begin with the centrality of visualization to the museum experience. Dias' focuses on the process of constituting racial difference, arguing that it is associated with the ways in which race is visualized and suggesting that anthropological collections and museums were important "systems of evidence" in the conceptualization of racial difference. An important issue here is the fact that this process seems to be accomplished by liberals and social reformers, not reactionaries, and that we must be aware of the museum as a "democratic" space, open to the public, when we understand the ideological role which it played in the 19th century (and now). Baxandall and Kirshenblatt-Gimblett deepen this theme by exploring the "museum effect," the differences created when objects are moved from an original site, and the complex production of meaning in artifacts in different settings, encouraging us to look at the relationship between the makers of objects, the exhibitors of objects, and the viewers of objects that are exhibited.Readings:

Nélia Dias, "The Visibility of Difference. Nineteenth-Century French Anthropological Collections," in Macdonald, ed., The Politics of Display, pp. 36, 49-50.

Michael Baxandall, "Exhibiting Intention: Some Preconditions of the Visual Display of Culturally Purposeful Objects," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 33-41.

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, "Objects of Ethnography," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 386-416 (only). (Note: You will have already read the first few pages of this article for the October 20 class. Come back to it here in the context not of "authenticity" but of the creation of difference.)

Museum Visit: To be assigned depending on current exhibits.

December 8: Where do we go from here.

We have focused almost exclusively on the historic museum, particularly in the 19th century, the moment of its greatest impact and importance. At one level, it is not hard to critique museums and museum practices in the way in which they solidify discourses about difference, hierarchy, and power. But the museum (particularly in its largest sense as museum or exhibition or fair or theme park or heritage site, etc.) remains an important, even vibrant institution which can offer its visitors new insights and which can destabilize the very discourses that museums have created in the past. The articles this week offer suggestions, from the curators' viewpoint, as to how this can be accomplished. Gurian wonders how best to design exhibits that can help people learn and realizes that curators must work against the discipline that has taught them what "appropriate behavior" in museums is. Vogel argues that museums always "recontextualize and interpret objects," and one should not apologize for this. Rather, by discussing specific exhibits, she suggests how curators must be "self-aware and open about the degree of subjectivity" in their collections. Using a somewhat thicker theoretical approach, Porter explores the ways in which museums constitute masculine and feminine and then describes a series of contemporary exhibits in Britain and northern Europe that challenge conventional readings. And Jones suggests now exhibitionary practices can rework the British colonial legacy. The exhibits discussed in these articles are just a few of many (see the optional reading for this week for more) which have been mounted in the past decade that suggest that the museum and its related exhibitionary institutions remain very much engaged in a struggle over how knowledge is to be shaped.Readings:

Elaine Heumann Gurian, "Noodling Around with Exhibition Opportunities," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 176-190.

Susan Vogel, "Always True to the Object, in Our Fashion," in Karp and Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures, pp. 191-204.

Gaby Porter, "Seeing through Solidity: A Feminist Perspective on Museums," in Macdonald and Fyfe, eds., Theorizing Museums, pp. 105-126.

Jane Peirson Jones, The Colonial Legacy and the Community: The Gallery 33 Project," in Ivan Karp, Christine Mullen Kreamer, and Steven D. Lavine, eds., Museums and Communities. The Politics of Public Culture (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992), pp. 221-241. [Course Pack]

John Berger, Ways of Seeing (Penguin), 1972, Chapter 2, 3.

Optional:

Ivan Karp, Christine Mullen Kreamer, and Steven D. Lavine, eds., Museums and Communities. The Politics of Public Culture (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press), 1992.

Museum Visit: Find a contemporary museum or an exhibit at a "mainstream" museum that purports to be "deconstructive" or otherwise postmodern in its reading.