![]()

ALUMNI MAGAZINE

AUGUST 1999

| FEATURES | ||

| LETTERS | ||

| AROUND TAPPAN SQUARE | ||

| A STUDENT PERSPECTIVE | ||

| HISTORIAN'S NOTEBOOK | ||

| ALUMNI NEWS | ||

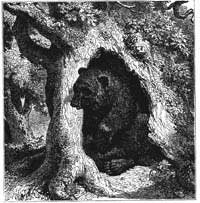

| THE BEAR NECESSITIES | ||

| ONE MORE THING | ||

| STAFF BOX |

the bear necessities

In June 1977 I was crew chief of an archaeological survey in the National Petroleum Reserve on the North Slope of Alaska. Six of us were working and camping together and were the only humans within 100 miles.

We returned to camp around 10 p.m. after a long day of searching for and mapping archaeological sites across the treeless tundra. Fortunately it was full daylight, and from a distance we could see that our site was demolished. Tents and supplies were flattened and torn, and equipment and food were scattered everywhere. In the midst of our camp was the cause of this revelry: a grizzly bear, who was having a simply wonderful time.

That was my first encounter with a wild bear. I had been in Alaska for less than a month, but over the next 20 years, I would meet many more, both grizzlies, including the famous Alaskan brown bear, and black bears, which are found in a variety of colors. Luckily, I survived the rendezvous without any injuries to the bears or me.

So when a short thread developed on the OC-Alum listserv about bear encounters, bear behavior, and advice about what to do when meeting one, I couldn't resist throwing in my two cents. And, now, as the summer months beckon many of us to parks, campsites, and hiking trails, it seems appropriate to share the information.

All bear encounters differ, and it's important to observe your surroundings and not panic. A bear rooting in the garbage or snacking on someone's picnic may look amusing on film, but can become a real danger in the wild. When a bear learns that people and food tend to be co-located, its natural aversion to humans is overruled by its voracious appetite. Once this happens, the bear must be relocated--a tactic that frequently is a temporary expedient since bears can cover a lot of country very quickly. If a bear repeatedly raids human settlements, it often must be destroyed before someone is seriously hurt or even killed. When people are careless, bears pay the price.

If hiking or working in bear country, particularly in an unpopulated area, it's a good idea to make noise. As peaceful as a quiet stroll in the woods may seem, it's much safer to keep up some constant racket to prevent unfortunate surprises. If you do meet a bear on the trail, don't run. Make noise to let the bear know that you are there, wave your arms, and back up slowly. Don't contest the issue with the bear. Also notice what the bear is doing. A sow with cubs or a bear guarding a kill is much more likely to be aggressive. Retreat carefully, but if charged, play dead--drop to the ground and curl up with your arms over your head and neck. If you encounter a bear in your camp, call the ranger and arm yourself with some pots and pans to clang together.

passive behavior is best. The smaller black bear, however, can sometimes be chased away by more aggressive behavior such as throwing rocks or waving branches. Black bears have been known to stalk or hunt people, so it's best to put up a fight if you can't seek safety by climbing a tree.

As for that first bear encounter in 1977, we managed to scare away the bear with pepper spray and several near-misses with the shotgun slugs, as one of the crew members with me was an extremely good shot. The grizzly didn't go far, however, and, after awhile came back. We hastily evacuated camp and watched in amazement as the bear rolled in the spot where the repellent had been sprayed an hour before. Again we managed to chase away the bear with well-placed shots. It was another Pyrrhic victory, however, as the bear soon turned the tables and chased us out of camp.

These repeated skirmishes went on for about 24 hours. We didn't want to kill the bear; after all it wasn't threatening us directly, just disputing the possession of the food in our camp. The incident finally ended when our helicopter came from the base camp to move us to a new survey area. The helicopter also chased the bear for several miles--giving it a good dose of negative reinforcement that hopefully deterred future camp raids.