|

|

|

|

To understand the problems threatening Oberlin's community, you need to replace the wide-angle lens with a telephoto. Zoom in, and festering problems come into focus: A persistent 25 percent poverty rate, dismal standardized test scores, substantial job losses, and a rising crime rate. The future of the town's only hospital is uncertain. Census figures show a 5 percent drop in population in ten years. The reasons for the latter decline are complex, but have a lot to do with the schools, a housing crunch, and dwindling job opportunities. All this makes Oberlin seem more like a big city than a pastoral college town. As

the town struggles to manage these problems, so does the College.

Recognizing that what's good for the city is also good for the

College, Trustees recently earmarked $350,000 to establish the

Oberlin Partnership and work with town leaders to resolve some

of the more pressing crises. This goes beyond altruism -- although

the College's long history of social responsibility surely plays

a part. Mainly it's about self-preservation. Unresolved, town

problems can quickly become College problems: A community in distress

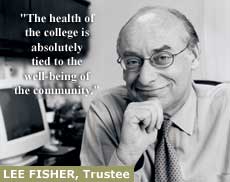

makes a "The health of the College is absolutely, unavoidably tied to the well-being of the community in which the College is located," says Trustee Lee Fisher '73, former Ohio attorney general and now executive director of the Cleveland-based Center for Families and Children.

Failure

in the Schools

Regardless

of the school system's successes, the Ohio Department of

Education grades Oberlin among the worst-performing districts

in the state, based on mandatory proficiency tests that

began three years ago. The last report card, for the 1998/1999

school year, gave Oberlin the equivalent of a big, red "F."

The district met only seven of 27 state standards, ranking

it with larger, more urban districts, like Lorain and Cleveland,

among Ohio's worst performers. In fact, Oberlin students

did so poorly that the the district was declared to be in

a state of academic emergency, the lowest classification.

Using proficiency tests to measure the overall effectiveness of a school system is still hotly debated. Critics argue that a district could "teach to the tests," enabling its students to test well, while cheating them of a well-rounded education. But even Oberlin school administrators, who initially dismissed the test results, now acknowledge that all the college-bound graduates and the merit scholars don't outweigh low test scores. "We tried for a little while to say [to the state], 'You're barking up the wrong tree, we haven't got time to do that,'" says a frustrated Francine Toss MA '71, director of pupil services for the school district and a liaison to the College. "But state officials had a different opinion, and it becomes a very high-stakes opinion when it hits the headlines. If you look at the paper, you'd think we don't prepare anybody for anything. But," she adds with determination, "we will meet the challenge." Even beyond the obvious value of providing a stellar education to Oberlin youth, the health of a school district can make or break a community. "Strong schools make it easier to attract residents and businesses. Weak schools repel them," contends Oberlin City Manager Rob DiSpirito. "It is a fact that a lot of parents have taken their kids out of the school system." "Right or wrong, we're losing out," agrees Larry Funk, president of the Oberlin Chamber of Commerce and one of the town's developers. "Just this week, two people with kids in elementary school told me they are leaving town because they don't want them going to middle school and high school here." Although

no formal surveys have been done, College President Nancy

Schrom Dye suspects that Oberlin's disappointing school

district performance affects choices that professors make

about where they send their children to school. "It used

to be that virtually everybody sent their kids to public

school here, but we've seen that change in recent years,''

she says. A weak school system, she notes, could produce

a domino effect, dissuading top-notch faculty, particularly

those with school-age children, from teaching at the College,

and, in turn, making the institution less appealing to prospective

students.

|

poor

magnet for top faculty and prospective students. So when push

came to shove, the Trustees didn't have much of a choice. Oberlin's

academic reputation was on the line.

poor

magnet for top faculty and prospective students. So when push

came to shove, the Trustees didn't have much of a choice. Oberlin's

academic reputation was on the line.