|

|

|

Around Tappan Square :: Page 10 :: WEBEXTRA Article 2 - Looking Back to See Ahead...

Jump to Page 1 : 2 : 3 : 4 : 5 : 6 : 7 : 8 : 9 : >10< of ATS

Looking Back to See Ahead: Panelists Discuss

Keeping

African American History Alive

Lost memories are lost history.

By Channing Joseph ’03

:::::

A recent panel discussion featured several alumni who made history themselves

in 1980, when they completed a winter-term project that recreated a slave

escape on the Underground Railroad. The alumni shared their personal recollections

on the experience, and they urged the younger generation to continue passing

on memories, and the wisdom and knowledge inherent in memories.

A recent panel discussion featured several alumni who made history themselves

in 1980, when they completed a winter-term project that recreated a slave

escape on the Underground Railroad. The alumni shared their personal recollections

on the experience, and they urged the younger generation to continue passing

on memories, and the wisdom and knowledge inherent in memories.

:::::

Imagine trudging 420 miles in the dead of winter, hiding in ditches to avoid passing travelers shouting obscenities and racial epithets and whom you believed might harm you. Imagine regularly being chased by dogs, or never knowing whether anyone would be kind enough to offer a warm meal to eat or a barn to sleep in for the night.

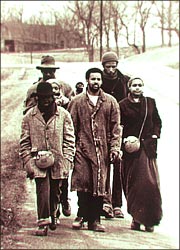

This is not an 1850s tale of an escaping slave, but the true-life experience of nine Oberlin students who, as a winter-term project in 1980, retraced the path of runaway slaves on the Underground Railroad, walking from Greensburg, Kentucky, near the Tennessee border, to Oberlin—freedom.

Back in 1978, the originators of the project—Lester Barclay, Herman Beavers, and David Hoard, all members of the Class of 1981—had originally planned to make the best of their winter break by traveling to Walt Disney World, keeping journals about the trip. But Hoard decided the project should be more educational, and he convinced the others to go along with what must have seemed, at the time, a crazy idea.

The group spent two years scouring Oberlin’s archives, searching slave narratives and other documents for clues on how to make their re-enactment as authentic as possible. In that time, they added six partners: Adrian Banks, George Barnwell, Gale Elison, Larry Spinks (all Class of 1981), Richard Littlejohn ’79, and Marzella Player-Credit ’82.

Attired in 19th-century garb borrowed from the theater program, carrying corn fritters and vegetable stew, and, most important, armed with a $9,378 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities Youthgrants Division, the group set out Jan. 2, 1980. During their 33-day adventure, which received national media attention, they’d both relive history and make their mark on it.

The three intrepid originators of this project returned to Oberlin April 12 to participate in a panel discussion titled “Preservation of African American History in Oberlin.” Anthony Marshall ’87, a member of the Oberlin African American Genealogy and History Group, was the fourth panel member. Part of the celebration of the 30th anniversary of Oberlin’s African American studies department, the panel was held in Hallock Auditorium in the Adam Joseph Lewis Environmental Studies Center.

Marshall, who is also president of the Oberlin Board of Education, spoke briefly about the importance of preserving Oberlin’s connection to the past and reminisced about his former activities with the Black Panther Party. “But I’m really more interested in what these other guys have to say,” he added enthusiastically.

|

The remaining alumni then shared their memories of that amazing winter-term project with a new generation of students and faculty members.

During the grueling journey, recalled Beavers, “My attitude was ‘thank God for letting me make it another day.’” Beavers is associate professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania and an award-winning author.s

“We passed through towns that were so far off the beaten track that we could have disappeared,” he said. “Our crossing of the Ohio River was, for the lack of a better term, comedic. The Coast Guard couldn’t let us cross without life jackets. If we had actually been in slavery, we would not have survived,” he laughed.

Initially, the three planners had decided to exclude women from the project, but they were convinced otherwise by faculty members, who prodded them to consider that “women were often the people to escape slavery because they were traveling between plantations to see children,” Beavers said.

The project changed Beavers’ understanding of the Underground Railroad.

“ The Underground Railroad is usually thought of as a network of sympathetic white people,” he said, but that conception overshadows the ingenuity of black people actively seeking refuge and cunningly searching for people who would help. “This idea of agency was all-important,” he said.

In pursuing the project, he wanted to promote an understanding of the contemporary struggles of African Americans. “One thing the project did was open up avenues of discussion that had been closed,” he said.

The significance of the project didn’t strike Beavers until the final day of the journey. Describing the group’s return, he said, “We arrived in Oberlin; it was 12 degrees that day. The gravity of what we had done hit me when the whole town turned out to see us. They let children out of school to see this.”

Hoard also reminisced about the project, emphasizing the educational intent behind the group’s work. “We had a one-act play, and we’d go to elementary schools and put on this performance to teach people about the historical importance of the Underground Railroad,” he said.

Building on the inspiration from his junior year at Oberlin, Hoard, the former leader of the Underground Railroad Project and now vice chancellor of development and university relations at North Carolina A&T University, has made a career of helping Americans remember their history. He was recently named chief executive officer of the International Civil Rights Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina. That facility commemorates the actions of four black A&T students who helped ignite the national desegregation movement by holding a sit-in in 1960 at a Woolworth’s whites-only lunch counter; it will open in February 2005.

Barclay was the last of the alumni from the project to speak. A senior partner at the Chicago-based law firm Barclay and Dixon, he expressed the sense of honor he felt on returning to his alma mater. “You can go anywhere in the world, and you can have a wonderful time, but there’s no place like home. Oberlin is like home,” he said.

Barclay emphasized that although their experiences were sometimes harrowing, they were in no way equivalent to the terror that escaping slaves would have felt. For one thing, the group had basic logistical assistance. One group member drove ahead each day, asking for food and housing from anyone willing to share barns or church houses.

In addition, the group had a large camper for use in emergencies. It

was put to good use in Belltown, Kentucky, where the students narrowly

avoided being attacked by an angry man with a baseball bat. They were

sleeping, with permission, in the barn owned by the man’s sister,

but for some reason, he didn’t want them there. Runaways lacked

such a safety net.

“ The ingenuity of the slaves is a story that needs to be told,”

Barclay said. “Sometimes slaves had to walk an extra 10 miles because

no one offered them a place to stay.”

Nowadays, based on his own experience of doing something he didn’t think himself capable of, Barclay encourages young students to believe in themselves. With wry humor, he reminds students who complain about difficult coursework that they are fortunate because “they didn’t pick any cotton today.”

“I leave you with a challenge,” Barclay said provocatively.

“It’s not only about preserving the historical legacy of the

Underground Railroad, but it’s also about transferring that knowledge

to the next generation.”

:: end

![]()

Booker

Peek (standing) introduces the panelists who discussed preserving

African American history: (left to right) Herman Beavers, David

Hoard, Lester Barclay, and Anthony Marshall.

Booker

Peek (standing) introduces the panelists who discussed preserving

African American history: (left to right) Herman Beavers, David

Hoard, Lester Barclay, and Anthony Marshall.