|

Issue Contents :: Feature :: Paths to Knowledge :: [ 1 2 3 4 ]

Paths to Knowledge

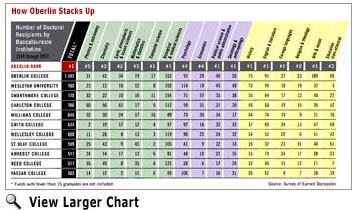

Oberlin alumni continue to earn more PhDs than do graduates of other baccalaureate

colleges. What makes so many Oberlin students commit to a life of the mind?

by Jim Lawless

Oberlin’s record of producing more graduates who go on to earn PhDs than all other baccalaureate colleges stands as a solid line that marches back to the 1920s. Science. History. English. Education. Music. Political science: All are fields of study in which Oberlin alumni dominate the list of liberal arts educated doctorate holders.

The Survey of Earned Doctorates, an annual study co-sponsored by the National Science Foundation and other federal agencies, reports that from 1999 through 2003, Oberlin graduates earned 566 PhDs. That’s 100 more than Wesleyan, which ranks second among the 217 baccalaureate colleges.

Ross Peacock, director of institutional research at Oberlin, has followed the figures for years. From 1994 to 2003, he says, 1,107 Oberlin graduates earned PhDs, more than a quarter of them in the hard sciences, where biology tops the list.

But the story of the PhD is not one of percentages and numbers; it’s the people behind the diplomas. OAM talked to 20 Oberlin graduates—all of them recent PhDs or current doctoral students—to gain a sense of why so many Oberlin students go on to earn doctorates. What attracts such students to Oberlin to begin with? And what, if any, common experience keeps graduates glued to the classroom for five to nine more years?

James Dobbins, chair of the religion department, thinks he knows. “There is a certain dispositional love of learning among our students that leads easily into a PhD,” he says. “Learning is their great joy.” James Dobbins, chair of the religion department, thinks he knows. “There is a certain dispositional love of learning among our students that leads easily into a PhD,” he says. “Learning is their great joy.”

And while not every Oberlin enrollee can be a chart-busting academic achiever, he adds, “something magical happens here that transforms them” or at least helps drive their already unusual thirst for knowledge.

Both alumni and faculty spoke of such moments of transformation: in many cases, a memorable moment of connection in which a professor reached out and affirmed a student’s capabilities to teach, research, explore, and otherwise live the life of the mind. The connection took place informally, say some, perhaps while drinking coffee or chatting after class, when the conversation turned to the student’s future and promise. Others pointed to a faculty-sponsored summer study program or a complex research project.

Siobhan Wilson ’98, for example, studied feto-maternal communication with biology professor Yolanda Cruz and formed a quick and fertile bond. “Yolanda is the neatest person I have ever met,” says Wilson. “The amount of attention she spends on students is amazing and inspiring.”

The pair spent hours in Cruz’s

research laboratory studying the Early Pregnancy Factor, a molecule

used by mammalian embryos to signal their existence to a newly pregnant

mother. The project was so strong that Wilson was offered both a

Fulbright Fellowship and a Churchill Scholarship. She chose the Churchill

and earned a master’s degree in pathology at Cambridge University.

Today, she is midway through a nine-year joint MD/PhD program at

the University of Wisconsin, one that Cruz helped her find.

“People who come out of this program can do laboratory and clinical work while studying patients,” says Wilson, who researches the biology of breast cancer. “There are a couple of really exciting developments. There are drugs now that can directly target cancer cells without harming normal cells.”

The importance of such a strong student-faculty relationship at the undergraduate level cannot be underestimated, says John Churchill, national secretary of Phi Beta Kappa honorary society. “It’s not enough to have really great students going to class and then going home to do homework. Colleges need to have a strong convergence of faculty and students—an absolutely superior, world-class, intellectually driven faculty that transmits ideas to students.”

It’s the spread of that intellectual excitement from faculty to students that matters, he says. But that transmission has to be returned. Professors themselves need to be continually nourished by the enthusiasm and ideas of students. “You have good liberal arts colleges around the country trying to do this,” he says. “But at Oberlin it is really happening.”

It happens, alumni say, because the campus is wired with intellectual excitement. “There was a buzz at Oberlin that you don’t feel in other places,” says David Getsy ’95, who earned his doctorate in art history at Northwestern University. “We were fascinated with learning. My Oberlin experience taught me how much fun it is to think creatively and deeply, and the faculty did it by example.”

Getsy came to Oberlin with a background mostly in mathematics and science and first took an art history course as a lark: “I wanted to have something to talk about at cocktail parties.” The class turned his life upside down. “I was swept away by this amazing course taught by Patricia Mathews,” he says.

By the end of his sophomore year, Getsy had landed a grant that allowed him to work in a gallery in New York City, where he witnessed “the art world in action.” The following summer, with a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, he conducted an extensive study on stock broker-turned-artist

Jeff Koons, known in the late 1980s and ’90s for his outlandish marketing techniques. The paper paved his way to grad school.

“By the time he was a senior here, David had done two honors projects, one in cultural studies and one in art history,” says Mathews, associate professor of art history. “He got highest honors in art history and was the first student ever allowed to curate a show at the Allen Memorial Art Museum. He is the most brilliant student I’ve ever had—he just absorbed information like a sponge.”

At age 32, Getsy is now at Harvard completing a J. Paul Getty Postdoctoral Fellowship. This fall, he’ll begin teaching 19th- and early 20th-century art history at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago. The author of two books on the origins of modern sculpture in Britain, he gives full credit to Oberlin’s art history professors for teaching him to think creatively.

Next Page >>

|