L.A. Story

On an alternately rainy and sunny day in Los Angeles in January 2009, a performance by the Oberlin Conservatory Symphony Orchestra nearly packed to capacity one of the world’s greatest concert halls. The concert —with its mix of anguished late romanticism, poetic piano lines, musical surrealism, and the sounds of conch shells—offered not only a sonic blueprint of the conservatory, but also a sense of the state of contemporary music in America, and of where both Oberlin and the art form might be going.

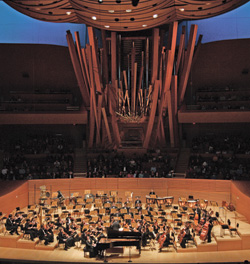

The Oberlin Conservatory Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Bridget-Michaele Reischl and featuring pianist Angela Cheng, at Walt Disney Concert Hall,

(photo by Craig T. Matthew/matthew Imaging)

The concert, presented by the Los Angeles Philharmonic as part of its Sounds About Town series, culminated the conservatory’s West Coast tour, and included Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 in D Major, and the world premiere of Huang Ruo’s Hanging Cliffs. Oberlin’s other appearances on the tour featured the new-music sextet eighth blackbird and members of the Oberlin Contemporary Music Ensemble performing pieces by Frederic Rzewski and Steve Reich,and the Prima Trio’s interpretation of Peter Schickele’s Serenade for Three.

“The extremely generous gifts of our lead donors, Jolyon F. Stern ’61 and Joan Lewis Danforth, made this tour a reality,” says Dean of the Conservatory David H. Stull. Stern is president and CEO of DeWitt Stern Group, Inc.; Danforth is an honorary member of Oberlin’s Board of Trustees. “Oberlin extends a very special thank you to them, and to all of our other supporters.” Major support for the tour was also provided by Adam Cohen ’91 and Jeannie Lurie; Jillon Stoppels Dupree ’79 and Anderson Dupree ’76; Hidong Kim ’87; and Harry Stang ’59 and Marta Stang.

Oberlin in the World

“The students in the orchestra really played their hearts out,” says Associate Professor of Music Angela Cheng, who brought an almost Chopinesque lyricism to the formidable Beethoven concerto. “Everybody was at the peak of their powers. For me it was a highlight I’ll remember for a long time.”

“In L.A. we experienced the joy of a lot of really excited alums happy to see Oberlin getting out into the world,” says Nicolee Kuester ’10, who served as principal horn for the Mahler symphony. “They were coming out of the woodwork.”

Touring is nothing new for Kuester; she also performed with the orchestra in China and at Carnegie Hall. In fact, tours such as these—which in the last few years have also included individual and chamber performances at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.—serve a number of functions, according to Stull.

Part of what’s important, he says, is the chance to play in a great hall—in this case the Frank Gehry-designed Walt Disney Concert Hall, which is renowned for its acoustics. “It’s not an experience that you can get by remaining on campus.”

These tours also allow the conservatory to reach out to audiences that are curious about music but don’t know much about it. The concerts give prospective students a look at the school and help engage existing students with new music. “Oberlin,” Stull says, “has a strong commitment to advancing contemporary music.”

There’s at least one other advantage, says Director of the Oberlin Orchestras Bridget-Michaele Reischl, who conducted the orchestra in Los Angeles and on the China tour. “It’s always healthy and hopeful to try to show the world what you’re doing and what you’re capable of,” she says. ”For the students performing, it’s a confirmation that what they’re doing matters to a lot of people. And that feeds our work, in an everyday kind of way, when we get back to the conservatory. It’s very energizing for us.”

Moving Forward

While all the pieces the orchestra performed on the West Coast tour were important, the world premiere of Hanging Cliffs, by Huang Ruo ’00, is the one likely to resonate longest with players and audiences—perhaps because it was so striking, and, to use a term that’s often abused, forward-looking.

Hanging Cliffs drew from both the Western tradition and from Huang Ruo’s own very different musical upbringing in China. The composition had a cinematic quality, with moments of dissonance on the woodwinds; what sounded like jungle cries; stabbing, insistent strings that evoked Shostakovich; and a sense of falling across vast distances. It seemed to bring together several kinds of music at once.

That doesn’t mean, though, that playing a piece rooted in two very different cultural traditions was easy. Reischl admitted that she has “never been so wrong” in trying to get a piece to sound right.

“Part of it was the cultural challenge,” the conductor says. “Huang Ruo was trying to bring Chinese sounds and traditions into the Western European orchestra. There were instruments that were new to us—there are no conch shell majors in the conservatory, and no slide whistles in our instrument collection. Imagine this bit of direction: ‘From bar 7 to 12 we want you to whistle.’ All of that was a challenge. But Huang Ruo was also asking our standard instruments to function differently in order to get the sounds of Chinese opera. It took a lot of experimenting, but that’s the advantage of having a composer who is alive and well. You can ask him, ‘Is that what you meant?’ Sometimes he said no.”

“I’m a longtime admirer of Dali and surrealism,” says Huang Ruo, an intellectually playful man whose music has been described as “strikingly assured” by the Wall Street Journal. “When you see his paintings they are often in the desert or a remote space, with bizarre images—a melting clock with ants, for instance. But it all makes sense if you’re in a dream state. It’s different from expressionism, where things are very vague, just suggested.”

Although Huang Ruo doesn’t see his music as divided into Eastern and Western elements, he does acknowledge that he had to “transform the orchestra to match the soundscape in my head. Imagine the orchestra as a big canvas, very dimensional, with colors and lines, but they don’t start in the same place—they are moving and shifting at all times.”

“To watch a composer working on a piece, and to intimately collaborate with him,” says Reischl, “is a very important part of our students’ education.”

The labors are worth it, according to Dean Stull, and not just for the students and the aesthetic pleasure the piece conveys. “The evolution of the canon is critical for art to survive,” he says. “It’s important for conservatories in particular to forge ahead—they can take chances more easily compared with many orchestras.”

Oberlin’s performance at Walt Disney Concert Hall, which since 2003 has been home to the Los Angeles Philharmonic, was an appropriately forward-looking gesture.

‘A Little Heaven’—Without Limits

Pianist Angela Cheng says the Oberlin Conservatory of Music is shaped by the fact that it enrolls undergraduates almost exclusively. Some note that this makes the place more idealistic and experimental in tone, less commercial than a place with older students.

“You have more than 600 students, all about the same age,” Cheng says. “That’s a very intense feeling. And the fantastic College of Arts and Sciences stimulates these students beyond music: They can explore other topics in an intense and focused way. And there’s real camaraderie at the conservatory.”

Huang Ruo, who came to Oberlin in 1996 after growing up in Shanghai and spending a year in Los Angeles learning English, remembers well his years on campus studying Cage and the European masters. “It was the opposite of a big city, but I enjoyed it immensely. Creative people—artists, musicians, and teachers—were around so I was never bored. And lots of performances—at midnight there was someone playing music. It was a little heaven: there were no limits placed on your expression.”

Nicolee Kuester, the French horn student, also played on campus—in the Littlest Bird, a woodwind quintet. She shares Huang Ruo’s view of Oberlin’s openness. “The concert format is a very old art form; it’s somewhat outdated and inaccessible to some people. New music is interesting because it opens up an old aesthetic.”

To Reischl, the conservatory’s philosophy is about being grounded and open in equal measure.

“One of Oberlin’s strengths,” says Reischl, “is staying connected to the cutting edge. The vision of someone like Dean Stull is a good example: It includes an incredibly strong interest in the Western tradition, which will never change. So it’s about continuing to invest heavily in the Western classical tradition, while trying to stay front and center at how the training of classical music is changing. Where are the new sounds coming from? Grounded doesn’t matter if the openness isn’t there.”

Contemporary music has a special place at the conservatory, though Huang Ruo worries that it’s not taken as seriously as it should be in the larger culture of classical music. “Oberlin believes that music should not just end at the end of the romantic era. We use the computer, we fly in airplanes—why can’t we listen to the music of our time?”

Dean Stull mentions eighth blackbird, the new music sextet that was founded at Oberlin in 1996. “Before their emergence, you’d think an ensemble of six people who come together to perform new music would have been a ridiculous proposition.” But eighth blackbird has thrived in its commissioning of new work from, among others, George Perle, Stephen Hartke, and Steve Reich, whose Double Sextet for the group won the Pulitzer Prize in 2009.

Stull describes himself as “boldly optimistic” not only for the conservatory but also for the larger world of classical music. “My iPod, like everyone else’s, is filled with music from Lynyrd Skynyrd to Leonard Bernstein,” he says. “Music will continue to thrive because people need to have music in their lives, music of complexity and importance. Even in a down economy, that human need doesn’t evaporate.”

Not Your Father’s Bach

(photo by Craig T. Matthew/Matthew Imaging)

Nothing less than the very future of music was the topic of a preconcert panel presented by four members of the Oberlin Conservatory of Music community before a standing-room-only gathering in Walt Disney Concert Hall’s BP Hall. The event was a prelude to the Oberlin Conservatory Symphony Orchestra’s performance.

David H. Stull, dean of the conservatory, opened the discussion by referencing the school’s commitment to historicalpractice, adding, “Our students must know how to engage the new,” as well as be part of creating it. He also deemed this an exciting time for classical music, and cited a New York Times article calling Oberlin “a hotbed of contemporary-classical players.”

(photo by Craig T. Matthew/Matthew Imaging)

At stake, he said, is the survival and development of the canon: In Bach’s day, only works that were deemed valuable for future generations were saved. Today, however, nearly every utterance is captured on YouTube and CD: “Your 8-year-old’s composition is saved in perpetuity. The evolution of art—the way in which we transmit it, the way we think about it, and the way in which we engage with it—has now taken on a very different meaning.”

Other panelists included composer Huang Ruo ’00; Elizabeth Baker ’76, a violinist with the Los Angeles Philharmonic; and Pulitzer Prize-winning composer David Lang, Distinguished Visiting Professor of Composition and Composer in Residence at Oberlin. Each contributed their thoughts on the issue, and questions were taken at the close of the discussion.

Huang Ruo talked about the evolution of Hanging Cliffs, which would be premiered at the concert, and the work’s connection to the sharp angles and many layers of Walt Disney Concert Hall, designed by one of his favorite architects, Frank Gehry. A composer who is often inspired by visual art, Huang Ruo said he envisioned Hanging Cliffs being played in that specific hall well before the actual performance. “I wrote a very challenging piece, as you will see,” he told the audience, adding, “Music can definitely happen in a universal way.”

Baker spoke about her path from Oberlin to the San Francisco Symphony and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, as well as the daily life of a working musician. She studied contemporary music at Oberlin, which she now considers a very practical move. She described how the complicated and various musical worlds she heard at Oberlin—which included electronic and tape-driven music—prepared her for later innovations such as Tan Dun’s instructions to musicians to make sounds with paper. “When we have to learn a completely brand new piece … it is amazing to me [that] we are able to … realize what’s in the composer’s head,” she said. “It comes in really handy when you have an education in contemporary music.”

Lang called today’s landscape “a seemingly contradictory world.” He conceded that the slumping economy and a recording industry in crisis had led to much doomsaying about music in general, but it is nevertheless a great time to be a musician. To be working at a time when the traditional ways of making a living are less inviting can be liberating, he said, and classical artists can draw from a wider palette of styles—world, dance, indie, electronic—than ever before. “The present world is a mess,” he said. “I mean that in the best possible way. It’s the greatest time to be a composer, as terrifying as it is.” —S.T.

Seattle and San Francisco on the Side,

with a Dash of Rock Star

The West Coast premiere of Steve Reich’s Double Sextet performed by (L to R): eighth blackbird’s Tim Munro ’02 (flute), CME’s Mark Cramer ’09 (clarinet), CME’s Leah Asher ’09 (violin), eighth blackbird’s Nicholas Photinos ’96 (cello), eighth blackbird’s Lisa Kaplan ’96 (piano), CME’s Jennifer Torrence ’09 (mallets)

(photo by © 2009 Ben Vanhouten)

As soon as audience members stepped into Nordstrom Recital Hall at Seattle’s Benaroya Hall on the evening of January 13, 2009, it was clear that this was not going to be a typical classical concert.

Alongside the glossy black grand piano were four shiny metal garbage cans and a stack of dinner plates, the percussion artillery for Frederic Rzewski’s daring new work, Knight, Death and the Devil, an Oberlin commission set to receive one of its first performances that night. Before long, percussionist Matthew Duvall ’95 of eighth blackbird would don goggles and work gloves, shattering the concert hall hush with the sounds of breaking glass and battered metal.

The program for the San Francisco and Seattle concerts that kicked off Oberlin’s West Coast tour struck an emphatically contemporary chord, featuring music by four living American composers: Peter Schickele (aka P.D.Q. Bach), Steve Reich, Stephen Hartke, and Rzewski.

The West Coast premiere of Steve Reich’s Double Sextet performed by (L to R): eighth blackbird’s Matthew Duvall ’95 (mallets), CME’s Eleanor Bors ’09 (cello) and Thomas Fosnocht ’09 (piano), eighth blackbird’s Matt Albert ’96 (violin) and Michael J. Maccaferri ’95 (clarinet), and CME’s Esther Fredrickson ’09 (flute)

(photo by © 2009 Ben Vanhouten)

The Prima Trio opened the concert with Schickele’s lighthearted Serenade for Three. The work’s hoedown-inspired finale included folksy glissandos from clarinetist Boris Allakhverdyan ’08 and violinist David Bogorad ’09, as well as a honky-tonk solo by pianist Anastasia Dedik ’06. In the middle of the program, the Oberlin-born sextet eighth blackbird played Hartke’s Meanwhile, full of novel sounds, from prepared piano to pitch-bending flexatones reminiscent of a musical saw.

The second half of the program was dedicated to a unique collaboration between eighth blackbird and students in Oberlin’s Contemporary Music Ensemble (CME), which is led by Ruth Strickland Gardner Professor of Music Timothy Weiss. The two groups joined forces to perform the Rzewski work, written for the occasion, and Steve Reich’s Double Sextet, an eighth blackbird commission. This would be the first time Double Sextet, which eighth blackbird previously played with pre-recorded tape, was heard with a full complement of live players, half of them from CME.

The combined ensemble played the works not just in San Francisco and Seattle, but also earlier in the season in Oberlin, and in New York City, where Reich and Rzewski attended rehearsals and concerts.

“It was really eye-opening,” says cellist Eleanor Bors ’09, who joined CME in the fall of 2008 as a relative newcomer to contemporary music. “Now,” she says, “I’m searching out much more new music.”

The Prima Trio (L to R): David Bogorad ’09 (violin), Anastasia Dedik ’06 (piano), Boris Allakhverdyan ’08 (clarinet)

(photo by © 2009 Ben Vanhouten)

Tim Munro ’02, a flutist with eighth blackbird, confesses to some initial skepticism: “I had a great experience at Oberlin, but I wondered if I wasn’t maybe looking at it all through rose-colored glasses.” Any reservations were shattered when rehearsals began. “It was a really fantastic experience,” he says; the students were “amazingly prepared and professional.”

Harpsichordist Jillon Stoppels Dupree ’79, who attended the concert, agreed: “It was very impressive. They took their work seriously but also had a great deal of fun.”

The collaboration impressed others, too.

In April 2009, Steve Reich was named the winner of the Pulitzer Prize in Music for Double Sextet. The recording broadcast on radio and television stations all over the U.S., from American Public Media’s Performance Today to The Colbert Report, was the very same version the Pulitzer jury considered: a live concert performance by eighth blackbird and the CME, recorded in Finney Chapel. In a press release announcing the win, Munro said it was “as close as I’ll ever get to being a rock star.”

—Charlotte Landrum

Scott Timberg is a Los Angeles-based writer who posts on West Coast culture at www.themisreadcity.com.