Making it New

Faculty and alumni composers discuss the ways in which Oberlin is a haven for those who live their life in music on the other side of the score.

In 1980, Kamran Ince ’82 arrived at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music as a 20-year-old transfer student. The son of a Turkish father and an American mother, Ince had spent most of his life in Ankara, Turkey, including two years at the university. “It was a very conservative French education —solfège, harmony, counterpoint,” Ince recalls. The small town in rural Ohio was a shock to this urban-reared young man, but Oberlin actually turned out to be liberating for him.

“Oberlin was still coming out of the ’60s,” he says. “It was really wild. All my friends were from the college, and it was an extremely intellectual environment. I could forget my conservative past with no limits on aesthetic thought. I would get up at 7 a.m. and write for two hours before breakfast. Until then, I had always composed on the piano, but I realized you start doing only what your fingers will do, so I started composing with no instruments, in my room, in the library.”

Oberlin was a crucial transitional experience for Ince. “I had been writing very nationalistic music, but Oberlin allowed me to get rid of my baggage,” he says. “It showed me the whole gamut of possibilities. It turned out to be the perfect place for me.” Now a prolific and much-performed composer, a winner of the Rome Prize and a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a professor of composition at the University of Memphis, Ince recreated that atmosphere of intellectual freedom and possibility when he founded Müzik İleri Araştırmalar Merkezi (MIAM), the Center for Advanced Research in Music at the Istanbul Technical University. Ince is codirector of MIAM, which he calls “a place that teaches people to think creatively and ask questions.”

The experience of finding one’s own voice is at the core of Oberlin’s composition program. Over the last half century, the conservatory has graduated young artists who have pursued a wide range of compositional styles, made different career choices, and found considerable success. They range from Pulitzer Prize winner Christopher Rouse ’71, who writes large-scale orchestral works, to Jonathan Dawe ’87, who composes operas that incorporate baroque fragments and use compositional procedures based on fractal geometry, to Ashley Fure ’04, who describes her music as “visceral, sculpted noise.” Many have followed the traditional path and acquired an academic post, such as David Schober ’96, assistant professor of music theory and composition at the Aaron Copland School of Music at Queens College in New York, or Margaret Brouwer ’62, winner of a Guggenheim Fellowship, who taught at the Cleveland Institute of Music and held the Vincent K. and Edith H. Smith Chair in Composition there from 1996 until her retirement in 2008. Others followed in the early footsteps of Fred Steiner ’43, hon.’07, and write music for film; still more have founded their own musical organizations.

Total Immersion

Unlike instrumentalists, who arrive at the conservatory with many years of technical training behind them, undergraduate composers are often relative beginners. The Division of Contemporary Music has about 60 students, with 40 in the composition department and 20 in TIMARA (Technology in Music and the Related Arts). “Our philosophy is to provide the most comprehensive experience, technically and musically,” says Lewis Nielson, professor of composition and chair of the department. “Our students are immersed in composing, acquiring technique, and trying a lot of varieties of musical material. In other eras, a period was associated with particular materials, such as the chromatic style of the late 19th century or the diatonic form of the late classical period. In contemporary music, every material of the past and present is laid out, as if in a cafeteria line, and the students have to learn to use these things. Our job is to make them accessible, helping the students discover what they want to write. They are finding themselves. That may be a cliché, but in the four or five years they are here, there’s a lot to learn. When they graduate, they know what they want to do.”

Broadness of aesthetic choice and range of opportunity is reflected in the learning environment at the conservatory. Composers study both acoustic and electronic composition and combine the two. Their fellow students are fine instrumentalists and singers, eager to experiment with brand-new music. The Oberlin Contemporary Music Ensemble, directed by Gardner Professor of Music Timothy Weiss, is considered one of the preeminent undergraduate performing ensembles in the United States—auditions for the 40- to 60-member ensemble are highly competitive. Prominent composers such as Sir Harrison Birtwistle and Joan Tower visit the campus for extended periods, offering undergraduates invaluable—and unique—close access.

“Contemporary music is one of the main functions at Oberlin,” Nielsen says. “Contemporary music isn’t something people do out of obligation. There is a strong sense of institutional commitment, a belief that you can’t train people to play only a narrow range of music. It’s a commitment that the entire faculty supports.”

Space to Try Everything

Christopher Rouse ’71 decided to be a composer at a young age, and through high school he prepared himself by listening to music and following scores. He refused to learn to play any instruments. “Six months on percussion was about the longest I lasted,” he says. Two pieces were required for the conservatory application, so he wrote an orchestral piece and a choral piece—his first-ever compositions. Walter Aschaffenberg ’51, chair of the department at the time, interviewed Rouse and told his astonished parents that their son was in. “I don’t know why,” Rouse says. “The pieces were sprawling, formless works. Maybe he saw in them an attempt to try something big, some spark of urgency and imagination, though lacking in discipline.”

“Contemporary music isn’t something people do out of obligation. There is a strong sense of institutional commitment, a belief that you can’t train people to play only a narrow range of music.”

Rouse’s Oberlin teachers were polar opposites on the aesthetic scale. But neither Emeritus Professor of Composition Richard Hoffmann, a serial composer who had been an assistant to Schoenberg, nor Emeritus Professor of Composition Randolph Coleman, whose interests lay in Cageian experimental composition, tried to convert Rouse to their point of view. “I did try everything and that was important,” Rouse recalls. “I wrote a serial piece, a graphic piece, a piece that involved someone announcing that piece would not be performed. But my heart was in what would ultimately be called new romanticism—not tonality, but expressivity. That wasn’t in the air at the time. I was behind the times or ahead of them. My teachers gave me space and let me run with it, and there was a benign quality in the way they did it. The only time I got in trouble was when I dared to use rock music in a piece—I was told to take it off my jury program. Even at Oberlin, that was not acceptable.”

Rouse sees that openness as a particularly Oberlin trait, an anomaly during an era when most university faculties, and thus new music as a whole, were in the 12-tone camp. “It was serialism or bust in a lot of schools, more for the graduate students, but when faculties were packed with serial composers, that would hit the undergraduates as well,” he says. “Oberlin was not a ‘my way or the highway’ sort of place. I had the freedom to do what I wanted—as long as it didn’t have electric guitar.”

More than 20 years later, Keeril Makan ’94, now an associate professor of music at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), recalls imbibing a similarly open attitude from Hoffmann and Coleman, his primary teachers in his last two years. “It was a very interesting balancing act between the two of them,” he says. “They were both passionate about their interests, which were very different, and they had respect for each other, so it worked well. Randy Coleman’s teaching involved a lot of discourse around music, fundamental questions about concepts and ideas rather than craft. Hoffmann, with his background in Vienna, gave a direct connection with the past that is hard to find in America these days.”

“Oberlin was a gateway to my career in terms of the preparation I received as a pianist, opportunities I had to hear great performers, and exposure, limited as it was, to composition. It was a major stepping stone.”

Jonathan Dawe ’87 studied with Richard Hoffmann and became intensely focused on the Darmstadt school of composition, but he was also playing crumhorn in the Collegium Musicum, taking advantage of the rich early music environment at Oberlin. Between these two seemingly disparate areas of music, he sees connections: “The transparency of texture, the complex counterpoint, how things are controlled by other things.” Today, Dawe, who went on to study with Milton Babbitt at Juilliard, writes music using compositional procedures based on fractal geometry—“generating new shapes from preexisting shapes”—employing fragments of baroque music as a base. James Levine and the Boston Symphony commissioned The Flowering Arts (2006), which is based on Charpentier. Dawe’s opera, Armide, is set 10 years in the future in postwar Iraq and draws upon music from Lully.

Back in the Day

Before the 1950s, composition was a peripheral activity at Oberlin. George Walker ’41, who in 1996 became the first black composer to win the Pulitzer Prize in Music for Lilacs for Voice and Orchestra, arrived at the conservatory as a 15-year-old piano student. Very little contemporary music was even being played at the time, let alone studied (although Bartók did come to campus once), so Walker took a semester of composition with Norman Lockwood “to see what it was all about,” he says. Walker graduated with the highest honors in the class, intent on becoming a concert pianist. His next stop was the Curtis Institute of Music to work with Rudolf Serkin, but he was interested enough in composition to also study with Rosario Scalero. Walker ultimately turned to composition and teaching as an alternative to the rigors of a touring career, finishing his studies at the Eastman School of Music and with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. The composer of more than 90 works, Walker retired from Rutgers University in 1992. “Oberlin was a gateway to my career in terms of the preparation I received as a pianist, opportunities I had to hear great performers, and exposure, limited as it was, to composition,” Walker says. “It was a major stepping stone.”

Kamran Ince

(photo by Merih Akogul)

Christopher Rouse

(photo by Jeffrey Herman)

Keeril Makan

(photo by Scott Irvine)

Fred Steiner is a successful composer and conductor of film and television music; some of his most famous themes are from the Perry Mason and Star Trek television series. Today he is a recognized authority in the field of film-music studies, writing and lecturing on movie music; he earned his PhD in musicology at the University of Southern California in 1981. Steiner studied composition at Oberlin, but only after three difficult years as a cello major. “I could never satisfy my cello teacher no matter how hard I practiced,” he says with a mixture of humor and resignation. “When it came time for the faculty to vote students into the senior class, my cello teacher was the only one who didn’t vote for my promotion. I had taken theory with Norman Lockwood of the composition faculty. He came to me in the hall one day and said, ‘I’m going to take you on as my composition student.’ That changed my life.”

Upon graduation, Steiner moved to Greenwich Village and found a job composing for CBS radio. When Lockwood retired from Oberlin (also migrating to Greenwich Village), Steiner reciprocated by getting Lockwood some work at the station. “When we were both there,” Steiner says, “I remember complaining how writing for radio was sort of a drag. He told me to just think of composing as a circle: ‘It’s a perfect shape, but within that circle, there are so many variations of things you can do.’”

Birth of the Cool and the New

New music first began to have a significant presence at Oberlin in the mid-1950s, when David Robertson, then the dean of the conservatory, started a contemporary music festival that was held during the first week of the second semester. Composition became a major in the mid-1960s, and the teachers—Aschaffenberg, Hoffmann, Coleman, Joseph Wood, and later Ed Miller, most of whom came out of the theory department—were to be its anchors for several decades. Gradually, composition and new music became more of a presence on campus. In 1970, Coleman started the New Directions concert series, which distributed the new music concerts throughout the school year and brought in many well-known composers, including Pierre Boulez and Iannis Xenakis. In 1983, Coleman changed the program into a thematic series, Contemporary Focus, which looked at post-modernism, minimalism, and other currents in composition, with associated lectures. Coleman recalls, “We did a lot of good PR: John Pearson [Oberlin’s Young-Hunter Professor of Studio Art] had the students in his lithography class make dazzling posters. They attracted people to the concerts, which were extremely well attended.” The interest has continued to build: today, about one-third of the more than 500 concerts and events presented each year on campus feature new music.

Another important step in the growth of new music was the birth of TIMARA. Teachers from the theory department who were interested in electronic music attached themselves to the project, which evolved from a 1970 winter-term project of interdisciplinary performances. Coleman recalls those first years: “There were no computers, just generators and tape, really crude stuff. They made a place in the basement, put the gear in there, and got a technician to run it. All gear had to be fabricated. Each one was unique.”

TIMARA gradually acquired more faculty members, including Emeritus Professor of TIMARA Gary Lee Nelson, who played a key role in shaping it, acquiring program status, and finally major status in 1989. TIMARA often served as a route into composition for college students. Associate Professor of Computer Music and Digital Arts Tom Lopez ’89, who now chairs the TIMARA department and directs the Division of Contemporary Music, graduated from the college with an individual major in computer music, because there was no TIMARA major yet. He had originally intended to major in philosophy. Arlene Sierra ’92, who is now based in London and teaches composition at Cardiff University, had been a serious piano student in high school, but did not want to be a concert pianist. A college history major, she was enrolled in secondary study in piano at the conservatory when she discovered TIMARA. “I had played synthesizer in rock bands in high school, and it seemed like a way to be creative, not give up the piano, and keep doing music,” Sierra says. She earned a double degree in TIMARA and East Asian studies. “Oberlin was the only place where that could happen,” she says.

Sierra found TIMARA “so Bohemian and hip, with everyone doing something creative and strange. I was meeting great players, too, and by my third and fourth year, I was figuring out how to write pieces for electronics plus violin.” Sierra became more interested in writing acoustic music, and Michael Daugherty, who was then teaching in the composition department, suggested she enroll in his class. Daugherty and Conrad Cummings of TIMARA urged her to apply for graduate school at Yale, and she was admitted to the master of music program in composition.

Jonathan Dawe

(photo by Peter Konerko)

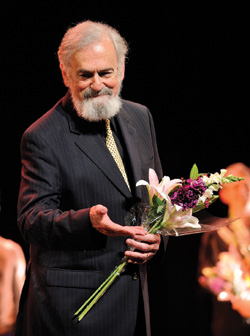

George Walker

(photo Courtesy Of George Walker)

Fred Steiner

(photo by Al Fuchs)

Today, Sierra writes chamber and orchestral music, including a world premiere commission in December 2009 for the New York Philharmonic, and believes that her background in electronic music at Oberlin was an important formative experience. “Exploring sound with electronics is not far from exploring it with an orchestral sound mass,” she says. “It felt like I was on a very natural path. And the way I write now is very much influenced by the layering and splicing I did with the electronics.”

TIMARA is now one of the foremost undergraduate programs in electronic music. Alumnus and Assistant Professor of TIMARA Peter Swendsen ’99 says, “We’re one of the few programs at the undergraduate level in the country, and arguably in the world, where students can focus on composing electroacoustic music. There are many that look at technology and engineering, but few that combine technical and compositional work in the way that we do, and few that have been doing it as long as we have.” Nielson and Lopez have also worked hard to eliminate any curricular barriers between acoustic and electronic composition. “The first-year course sequence is identical for composition and TIMARA majors,” Lopez says. “We have also devised the graduation requirements so that if a composition major wants to pursue TIMARA as well, or vice versa, they can.” TIMARA students are also encouraged to incorporate acoustic instruments in their work.

The study of jazz is also a key element of Oberlin’s commitment to new music. The program, built by the late Professor of African American Music Wendell Logan, integrates performance and composition. Michael Mossman ’81, director of the graduate jazz program at Queens College, as well as an active performer, composer, and arranger, was a double major in classical trumpet performance and jazz studies (and a double-degree student in sociology and anthropology). He says that his rigorous training at Oberlin has been central to his success. “Wendell had a PhD in composition, and his approach was not ‘just get swinging,’ which is so often the case in jazz, but a real sense of the content of the music,” Mossman says. “He asked devastating questions, like ‘Why did you write that?’ and you had to have a good reason. Jazz involves more improvisation, but whether it’s jazz or classical, you have to say, ‘Why did I choose to put this note there?’ That’s what gives the music a lasting value, as opposed to something that sounds cool for the moment. I’m sure that’s why I got a lot of work in New York: lots of people can write jazz arrangements, but there are underlying things that give the music merit. I learned that by studying with Wendell.”

The Oberlin Lab Experience

Oberlin attracts faculty who are interested in close work with undergraduates. “Teaching is the primary thing here,” Nielson says. Assistant Professor of Composition Josh Levine appreciates “the opportunity to engage with students on an idealistic as well as practical level, where you are really dealing with the discovery of their own creative process.” He adds, “With graduate students, that sense of excitement and discovery has often become tainted by a degree of cynicism. Working with undergraduates, especially ones as bright and quick as the students at Oberlin, makes me feel as though I’m having a stronger constructive impact as a teacher.”

“There’s no better place to study composition. To be a composer, you must have some laboratory-like experience, and Oberlin provides that, because there is a community in which an active engagement with new music is important.”

Composer David Lang, founder of the renowned new music institution Bang on a Can and the winner of the 2008 Pulitzer Prize in Music for The Little Match Girl Passion, started his appointment as Distinguished Visiting Professor in Composition and Composer in Residence in 2008-09. He visits the campus several times a year to teach lessons and master classes and offer seminars on such topics as how composers have responded to politics. Lang, who teaches graduate students at Yale, finds the Oberlin students “really talented and smart. I enjoy the fact that they are young, and trying on different kinds of clothes.”

Oberlin composers recall other benefits of the Oberlin atmosphere. The small-town setting means that the professors live nearby, and will make the extra effort for their students. During his student years, Lopez recalls, “I took for granted some exceptional things–that a teacher would come to a practice room to hear me play a solo piano piece I was working on, outside of class. It’s not so easy to get them to do that elsewhere.” Fellow students also contribute to the ongoing musical ferment. Ashley Fure, now a PhD student at Harvard, where there are no instrumental majors, says, “I miss hearing 17 pianos playing 17 things at once, and being immersed in that saturating musical climate where every night students are giving recitals and putting on their own productions. It was a big luxury to be able to experiment with such high-quality players, to bang on somebody’s practice room door and ask them to ‘try this on the violin.’” It has now become almost routine to see a student-written work on a senior recital. The day-to-day activities of the conservatory are also part of the education. “To be able to sit in on an orchestra rehearsal at Oberlin is the best orchestration class you could ask for,” Arlene Sierra recalls. “I’d watch [Professor of Conducting] Bob Spano conduct a piece, and make the first violins repeat something 50 times, and realize, oh, that’s pretty tricky.”

In recent years, one major feature of that “saturating musical climate” has been the elite Oberlin Contemporary Music Ensemble, directed by Tim Weiss. “When I first got here, in 1992, CME did not meet for the same amount of time as a large ensemble, such as orchestra,” Weiss says. That has now changed, he points out, an example of how at Oberlin new music is at the center, rather than the fringe, of musical life. Weiss asserts: “There’s no better place to study composition. To be a composer, you must have some laboratory-like experience, and Oberlin provides that, because there is a community in which an active engagement with new music is important.” Lopez points out that the laboratory extends beyond new music: “The overall community is interested in new and experimental work in general. There are collaborations with dancers, choreographers, video artists, people working in sculpture.”

Lang says that an important aspect of his role at Oberlin is to bring the outside world to campus, and to get students to think about what it means to be a composer. “For example, I like the idea that music has a larger function than what it does to you individually,” he says. “Music is about communication. One of your missions as a composer is to take ideas you are working with and spread them through the world, to be in dialogue with other disciplines, and with other parts of our society. It’s important for students to know that the outside world is there, hungering for these ideas. I’m going to the trouble of writing music, I want it to be heard, played, and thought about.”

The college is an important resource for Oberlin composers, a number of whom pursue double degrees. Arlene Sierra’s compositions often refer back to the field of her academic major, East Asian studies, which covered art history, philosophy, political history, and language. “It was multidisciplinary, a way to be voracious as a student,” she says. “When I went to graduate school, I had an epiphany and realized that being a composer means studying what you want to study all the time. You need a huge amount of technical knowledge, but what inspires your music has a lot to do with what you are reading, seeing, and learning about.” Michael Mossman believes that pursuing the double degree taught him to multitask. “I have graduate students who complain, ‘I’m so busy, how do I finish this work?’ They don’t get a lot of sympathy from me–they’re so narrow in focus, so obsessive with one little thing. When you are writing and performing, it’s good to get your mind out of it sometimes.”

Making It While Making It New

The new music collaborations formed at Oberlin have gone on to have an important impact beyond its walls. The Chicago-based ICE, or International Contemporary Ensemble, a highly regarded collective of players and composers, got its start at Oberlin. Mario Diaz de León ’04, a TIMARA graduate now based in New York City, arrived at Oberlin after two years of playing in bands and touring, with the goal of writing both electronic and acoustic music. “I met some great people,” he says. “We formed the Shinkoyo collective, a community of artists and musicians, very quickly, and it is still going strong today. We collaborate on various projects together, as well as a record label and a performance space. It’s like home base for me.”

Arlene Sierra

(photo by © Ian

Phillips-Mclaren)

Ashley Fure

(photo by Ella Daue)

Mario Diaz de León

(photo by

Doron Sadja ‘05)

While many Oberlin composers still follow the traditional American path to graduate school and an academic career along with their composing, other paths are now open. Oberlin’s atmosphere of openness, experimentation, and interdisciplinary work gives its graduates a sense of possibility. “Once, 80 percent of composition students went to graduate school; now it’s more like 50 percent,” Nielson says. “There are more options now. They may work in sound design in theaters. Some get grants and study abroad. Some just go abroad.” Many Oberlin graduates form their own performance ensembles: Peter Flint ’92, a double degree in history and TIMARA, started Avian Music, which performs themed concerts featuring experienced and emerging composers; in Seattle, the Fisher Ensemble, led by Garrett Fisher ’91, incorporates singing, acting, music, and movement; and Greg Saunier ’91 started Deerhoof, a cross between an indie band and a classical new music ensemble.

“These kids are entrepreneurial and want to make it as performers and creative people,” Coleman. “They do the historical art music and their own music, start their own ensembles, improvise, and write their own music. It’s normalized at Oberlin. And it will have an impact–these kids don’t just go through the motions. They want to play and have an audience.”

Take Diaz de León. For his last semester at Oberlin, he did an internship at Roulette, the new music presentation space, which helped his post-college transition to life in New York, which, he notes, is “full of Oberlin people.” His recent activities include finishing a CD of his chamber music for the Tzadik label, a commission for ICE and the Moving Theater dance group, a solo act of “heavy, noisy industrial music,” an art gallery exhibition of a video featuring his music (and another Oberlin friend, violist Glenda Goodman ’04), plus work on the Shinkoyo record label and organizing shows at its performance space in Brooklyn.

“I am not sure how to describe my life as a composer,” Diaz de León says. “I only write one or two pieces a year. The rest of the time I’m doing other things, like performing in rock venues, improvising, and collaborating. I suppose I see classical composition as one very important aspect of a larger musical activity. I need all of those other things to keep me inspired to compose. In that way my musical life is still a lot like Oberlin, but on a larger scale, and with fewer classes.”

The Coleman Legacy

Randolph Coleman began teaching at Oberlin in 1965 and was a central figure in the composition department until his retirement in 2009. Coleman’s own compositional language leaned toward Cageian experimentalism, but his teaching was about questioning and keeping an open mind. “Randy is a philosopher,” says Tim Weiss. “For years, he would give the last lecture to the entry level music history class and pose the question, ‘What are we doing?’ The idea was to come up with a reason for playing new music—giving expression to things we are currently living with—or to force performers to bring new life to old pieces. His mantra was always ‘Make it new.’”

(photo by Roger Mastroianni)

“Randy Coleman let me be who I am—he never tried to turn me into what he would like me to be,” says Huang Ruo ’00, winner of the International Composition Prize in 2008. Keeril Makan ’94 says: “Randy was very inspiring. He had been teaching for a long time, yet whatever he was seeing seemed fresh to him. He took you to task, and tried to make you not be so attached to what you were doing. He encouraged you to try things out, to see that it was okay to fail, and learn from that. It was very healthy for me.” Makan now teaches a class in composition for non-musicians at MIT. “That idea of experimenting, that anyone can make music, comes from Randy,” Makan says.

Coleman was instrumental in spreading the gospel of new music on campus through his New Directions and Contemporary Focus concert series. In 1985, he established a system of eight technical modules for the first two years of the composition program. The idea of these intensive writing classes, taught by the faculty in rotation, was to have the students learn from each other. Composer Pierre Jalbert ’89, winner of the Rome Prize, says that the stylistic evolution of his own music reflects the diversity that he was exposed to in the modules. “They opened my eyes to all the possibilities.”

An entrepreneur’s way of life is not always easy, though. “It’s important to say that failure can happen,” Bill Palant told students at the symposium. It’s part of our job as educators, he said, to “prepare students for the career challenges” that will come their way.

In addition to chairing the composition department for many years, Coleman directed the InterArts Program from 1972 until 1977. A strong believer in the integration of artistic disciplines, and an advocate for players remaining in touch with their creative impulses, Coleman finds the variety of compositional styles and career paths pursued by composers today enormously encouraging. “This is the healthiest period for art music in history,” he says. —H.W.

New York-based writer Heidi Waleson wrote about the Selch Collection of American Music History for the 2008 issue of this magazine. Her work has appeared in such publications as the Wall Street Journal, Early Music America, Symphony, and Opera News.