|

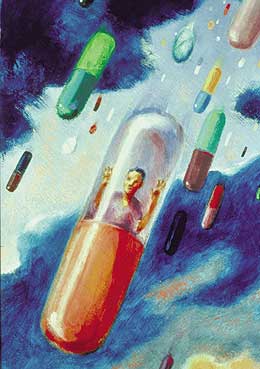

Sugar-Coating

The Problem Sugar-Coating

The Problem

Even with such potent drugs in the pipeline, another problem must

be overcome before anti-cancer drugs will work well. Some solid

tumors are so large that it is difficult to get any anti-cancer

drug to penetrate deeply inside the tumor. David Ranney says that

chemotherapy works initially to shrink the outside of these tumors.

But the inside never gets the drug and becomes resistant to it by

the start of the next chemotherapy regimen.

At home, patients endure a roller coaster of hope

and despair as their regressing tumors regrow. Ranney estimates

that 95 percent of standard chemotherapy agents are cleared from

the body's bloodstream before ever making contact with a tumor cell.

That's because the body is so good at ridding itself of toxic drugs

via the liver. "No delivery, no payload," says Ranney,

who founded two biotech companies and now runs a Dallas consulting

company called Global Biomedical Solutions.

For enough of a drug to reach the core of a large,

solid tumor, many patients must withstand massive doses of toxic

chemotherapy that kill bone marrow and sometimes heart cells. Raphael

Pollock, chair of the department of surgical oncology and head of

the division of surgery at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, relays

the story of three such unlucky patients. All were cured of tumors

in their muscles and other soft tissues, but the chemotherapy's

side effects required each to undergo a heart transplant.

"Obviously the treatments we have are less than

ideal," says Pollock. But Ranney, attempting to improve drug

targeting and action, has turned to a clever means of encapsulation.

As a pathologist at Northwestern University and elsewhere, Ranney

observed that white blood cells and viruses were two of the biological

agents that could penetrate deep into tissue cells. He also noted

that the cells and germs performed their fait accompli by covering

themselves in sugar. Why not cloak anti-cancer drugs in the same

biological coats that nature has devised?

The concept led Ranney and his colleagues at the University

of Texas Southwestern Medical Center to manufacture a platform of

sugar-based coverings called sulfated glycosaminoglycans. Various

types of sugars are mixed with anti-colon cancer drugs, emulsified

under high pressure, and freeze dried. The powder is later dissolved

and injected into various strains of mice, each with differing solid

tumors. Once inside the animal's bloodstream, the sugars recognize

special molecular receptors on the inner surfaces of blood vessel

walls, similar to locating a house by its address. The sugars then

bind to those sites, pulling the drug with them through the vessel

wall and into the nearby tissue. There, the sugar disguises the

drug from the body's clearance mechanism and eventually leads the

drugs into the depths of the tumor--to their final "street

address," Ranney says. "We are fooling the body into transporting

our own drugs for targeting."

As a bonus, Ranney's team encapsulates the drugs in

a time-release package that releases the chemotherapy payload slowly

and over a longer time, ensuring that a tumor does not shrink slightly

only to regrow soon after remission.

So far, Ranney's work is in its early stages. In one

strain of tested mice, 40 percent experienced complete regression

of their tumors after 90 days with the sugar-coated drug, compared

with 0 percent in control animals given non-experimental forms of

drugs. "With current advances in chemistry," Ranney sums

up, "we are now moving from exposed, highly toxic drugs to

packages of payloads that get the home address of the tumor cell."

Page 1 | 2

| 3 | 4

| 5 of Curing Cancer

|