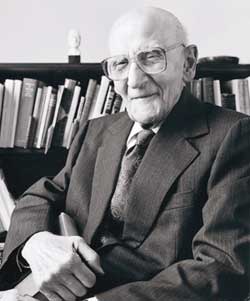

Of the ten members

of the Ward family who attended Oberlin College,

I was the only one to flunk out. For me, Oberlin proved too

loaded a proposition, too burdened by the ghosts and expectations

of my family's past. No one as thoroughly embodied the nightmarish

impossibility of my living up to my heritage as my godfather,

Professor Andrew Bongiorno. During the worst years of my life,

his very existence was a kind of reproach. From the time I

first began to speak, I had called this slender, fond, soft-spoken

man Uncle Andrew, and it was not until I was almost in my

teens that it occurred to me that we were not blood relations.

Andrew never asked that he be my godfather, nor that I be

named after him. As a devout Catholic he was always a little

puzzled as to how he was supposed to see to it that this child

of lapsed Protestants should attain the stature of Christ.

But beyond the height requirement, there was the matter of

my schooling. In a verse he composed on my first birthday,

Andrew predicted that as the son of a college dean I would

eventually become an austere contemplative, but he urged me

first to "eat your porridge" and "suck your bottle, then proceed

to Aristotle."

Of the ten members

of the Ward family who attended Oberlin College,

I was the only one to flunk out. For me, Oberlin proved too

loaded a proposition, too burdened by the ghosts and expectations

of my family's past. No one as thoroughly embodied the nightmarish

impossibility of my living up to my heritage as my godfather,

Professor Andrew Bongiorno. During the worst years of my life,

his very existence was a kind of reproach. From the time I

first began to speak, I had called this slender, fond, soft-spoken

man Uncle Andrew, and it was not until I was almost in my

teens that it occurred to me that we were not blood relations.

Andrew never asked that he be my godfather, nor that I be

named after him. As a devout Catholic he was always a little

puzzled as to how he was supposed to see to it that this child

of lapsed Protestants should attain the stature of Christ.

But beyond the height requirement, there was the matter of

my schooling. In a verse he composed on my first birthday,

Andrew predicted that as the son of a college dean I would

eventually become an austere contemplative, but he urged me

first to "eat your porridge" and "suck your bottle, then proceed

to Aristotle."

By

the time I entered Oberlin, however, I still hadn't proceeded

to Aristotle, and my attitude around Andrew was one of tongue-tied

shame and embarrassment. I would sit choking in the rarefied

atmosphere of Andrew and Laurine's book-lined living room,

where they sat expectantly, poised on the edges of their

chairs, searching in vain for some tiny sign of an intellect

pulsing under my downcast brow.

As

Andrew heard from his colleagues of his godson's absences

and delinquencies, he dutifully reported all to my parents.

When I was on the verge of flunking elementary Italian,

he arranged for me to come to his office on Wednesday evenings

to sit before this translator of Castelnuovo, this legendary

explicator of Dante, and miserably conjugate, say, the present

tense of the verb andare.

But

after all he tried to do to help me, I dormire'ed

through the final exam, and as I limped through my last

semester of academic probation, I found I could not face

him. If I glimpsed his papal figure strolling down East

Main, I would duck into a store until he passed. When Oberlin

finally cast me out, I could not bring myself to tell Andrew

in person but instead left an anguished little note under

the door to his office, where, I am ashamed to say, I could

see him sitting, correcting papers at his desk.

I

tiptoed off into limbo as Andrew proceeded into one of those

protracted retirements in which Oberlin seems content to

exile its greatest teachers. (It used to pain him to receive

invitations to the annual "at home" at the president's house,

where the guests were all from town. "It is an invitation

I wish I were spared," he once wrote me. "It serves only

to make me feel more than ever a stranger in a place that

was once my home.") He wrote sometimes to inquire about

my progress down the path of least resistance. But we did

not really correspond until ten years later when he began

to come upon my writing in The Atlantic Monthly.

His

praise for my essays and parodies was like a benediction,

and for years I used to frustrate the copy-editing departments

of a whole string of magazines by passing everything I wrote

through the Bongiorno sieve. I still have the little typed

scraps he sent back, noting the page and line numbers where

he'd come upon a colon doing the work of a semi colon, an

independent clause indecently displayed without a comma,

a heedlessly misplaced modifier. He saved me infinite embarrassments,

and gave me a leg up with my unsuspecting editors.

"I

have concluded," he once told me when I began to show signs

of progress, "that you were never uneducable, Andy. Only

unschoolable."

It

was not until the early '80s when I decided to write a novel

about India, that Andrew's influence became less professorial

and more godfatherly. As I fantasized my way into the perilous

and sometimes dismal world of 19th-century India, I began

considering seriously for the first time questions of suffering

and free will. When I periodically lost my nerve, I began

to turn to Andrew more and more, until we were exchanging

long epistles on faith and the mystery of God's purposes.

As

the merciless architect of the world my characters inhabited,

I guess I didn't believe in God so much as identified with

Him. I asked questions a lesser professor might have dismissed

as sophomoric: Is God just and all-powerful? Or unjust and

all-powerful? Or not all-powerful but only just, in which

case, who needs Him?

If

God were just and all-powerful, Andrew replied, then His

justice was the very mystery Andrew himself embraced. He

assailed the notion of an all-powerful, unjust God as the

Byronesque excuse of the guiltless, tragic hero. And, he

gently suggested, if God were just but not all powerful,

then perhaps the question was not whether we needed Him

but whether He needed us.

In my unbelief I had always felt as though I were feeding

from somebody else's trough. Andrew was pleased when, after

he had taken such pains with me, I finally concluded that

I was not an atheist nor even an agnostic but what he called

"an alienated Christian."

"Let

me confide to you," he once wrote, "that I was born five

months and 24 days before the death of Queen Victoria. Doesn't

that explain everything?"

No,

actually, it didn't. It did not explain, for instance, how

a man, who until his early middle age thought homosexuality

had expired with the ancient Greeks, could recognize in

his extreme old age the workings of God's grace in the grotesqueries

of Flannery O'Connor's parables or make his way past what

he called the "blood-and-guts" propaganda of D.H. Lawrence's

short stories to a "well of English undefiled." Though there

was nothing in the way Andrew lived his life that would

have ruffled the most decorous Victorian, he was a man of

the 20th century.

next

page