As

improbable as it seemed at the beginning, these low-tech efforts

obliterated the deadly disease. Records of the horror of smallpox

epidemics exist in Hindu manuscripts 3,000

to 4,000 years old, and the disease has been etched into the

history of every country and culture. In the 20th century

alone, smallpox killed at least 300 million people and left

tens of millions of survivors horribly scarred, disfigured,

and grossly impaired.

|

|

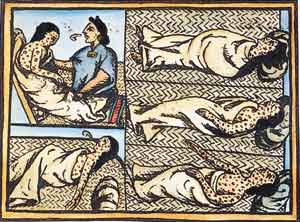

New

World Indians, with smallpox contracted from European

settlers, ministered to by a medicine man: illustration,

16th century.

|

The eradication

of smallpox was arguably the greatest triumph in medical history.

Never before had the efforts of health workers led to the

disappearance of any infectious disease, let alone a viral

disease. Although viruses are relatively uncomplicated in

structure, almost nothing else about them is simple. Most

are little more than a string of genes surrounded by a protein

overcoat. Some are also bounded by a fatty envelope. They

are not cellular in structure and lack the ability to carry

out an independent metabolism. Strictly speaking, viruses

are not alive, although they share important attributes with

living things. Viruses can infect living cells and reproduce

before destroying the very cells they briefly called home.

As they have genes, they can mutate and, in time, viral populations

evolve.

Despite

the simplicity of its structure, researchers know relatively

few details about how the virus causes such gross pathology.

Although there are vaccines to protect uninfected people

from acquiring some viral infections, there are no medications

capable of curing patients already infected. No viral disease--not

hepatitis, polio, influenza, nor AIDS--has ever been cured

by medicine. Smallpox, an illness with no known cure and

caused by a deadly virus whose lethal mechanism is not well

understood, was the first infectious disease to be wiped

out.

Henderson

directed the WHO Smallpox Eradication Unit from the beginning

to the end of this incredible effort, hoping that he and his

colleagues would live out their lives with the assurance that

their accomplishment had been an unambiguous boon to humankind.

Unfortunately, that was not to be.

After

the pronouncement that smallpox was gone, WHO tackled the

thorny issue of what to do with remaining smallpox virus

stocks stored in laboratory freezers at sites around the

world. WHO recommended the destruction of all stocks except

for those in two places: the United States Center for Disease

Control in Atlanta, and the Institute for Viral Preparations

in Moscow. Research would continue at these two sites with

the goals of finding the DNA chromosome in isolates of the

virus and replicating the chromosome in a virus-free environment--in

fact, genetic cloning. This would determine the exact sequence

of DNA subunits in the chromosome, allowing scientists to

study safely the genes of this killer without using an intact

virus.

In

1972, even before smallpox had disappeared, the U.S. halted

almost all smallpox vaccinations except for medical staff

working with the virus and some military personnel. Today

almost no Americans younger than 28 (more than 100 million

people) have protection. For the rest of us, the question

of vulnerability is not at all clear. The duration of

smallpox vaccine protection has never been satisfactorily

determined. It is likely that most people from around

the world are vulnerable to its ravages if the disease

ever reappears.

The

final WHO recommendation was that on June 30, 1999, all

remaining virus stocks be destroyed. The rationale made

sense: it seems pointless to immunize people against a

non-existent disease. Almost half the world population

is unprotected, and a single case of smallpox anywhere

would create a medical emergency of unparalleled urgency.

According to WHO, the only possible sources of a new outbreak

are the vials of virus stocks stored in freezers in Atlanta

and Moscow. Destroying them would forever eliminate the

risk of a laboratory accident that could trigger a tragedy.

Thus

the uncomplicated recommendation of WHO was proposed as

the next logical step, which would presumably be the last.

Sadly, this is where the story turns ugly and where the

interconnectedness of all things becomes manifest.

Unless

we are truly a world gone mad, the assumptions underlying

the WHO recommendations began with the idea that the eradication

of smallpox was a magnificent boon for the common good

of all people, regardless of nationality or allegiance.

Another assumption was that scientists and governments

and all specialists with relevant expertise would cooperate

in ensuring that the disease would never again inflict

its horror. It was unthinkable that any individual or

group or government would abuse that tacit trust to further

their own political or economic or ideological goals.