|

||||

|

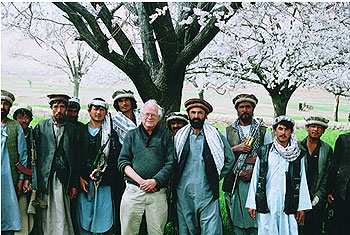

The Afghan warlord welcomed Joel Montague '56 for tea and talk of murder. Known as General Toofan, the commander holds sway in the mountainous District of Khamard--a bumpy four-hour ride north of the Afghan Provincial Capital of Bamiyan. But Toofan (or "Storm" as it translates into English), can also be a hospitable man. He invited Montague to his home last spring to discuss a variety of topics: the elusiveness of Osama bin Ladin, the devastation of drought, Monatgue's just-completed visit to a busy Afghan health clinic, and the murderous impulses of the ousted Taliban leadership. In a nearby village, a mass grave was filled with the bodies of 200 local teachers who had been slaughtered months earlier by the Taliban. They were victims, the general said, of "demented" local religious leaders who had insisted that the Afghans study only the Holy Koran. It was an absolute necessity, therefore, to entice primary and secondary school teachers back into the remote district. Undaunted by his unstable surroundings, Montague, a public health specialist with the international aid group Partners for Development (PFD), moved ahead with his overriding agenda for the meeting--to gain the general's blessing for a much-needed community-based water and sanitation project to benefit the rural villagers. After much discussion, the general warmed to the idea, but "made it known, in no uncertain terms, that if anyone was to be digging wells in the mountains, it would be his own 3,000 soldiers, who needed to be kept busy," Montague recalls. "He said that the community needs an example." Montague, who serves as chair of the board of PFD

in Silver Spring, Md., first visited Afghanistan while with CARE

in 1962, then spent the intervening years as a public health officer

for voluntary agencies in the U.S. and abroad. He and his colleagues

at PFD had correctly assumed that Afghanistan would be desperate

for help and swamped with refugees after the Taliban's fall. Well-experienced

in post-conflict situations and in potable water and sanitation

projects, PFD was thrilled when a well-regarded Afghan NGO, IbnSina,

asked about collaborating in such an activity with a network of

Afghan health facilities. Montague, who speaks Farsi, was the natural

choice to assess the possibility. As a lacrosse-playing Oberlin government major who'd already spent three of his high school years in England, Montague developed an early interest in international and humanitarian work. ("No different than many of his Oberlin classmates," he notes emphatically.) His steps to General Toofan's door can be traced back to studies at Oberlin and Johns Hopkins, and to post-college volunteer work in Spanish Harlem. A Fulbright Fellowship in 1960 sent him to Iran to study Farsi and tribal relations in Baluchistan. There, he linked up with CARE and spent nine years in Iran, Egypt, and Tunisia. Border crossings became second nature, part of the family. His Iranian-born wife, a physician, Shahnaz, he met in London; his daughter, Maryam, works in Morocco for an American non-profit; and his son, Jahan, is a doctor. After years in the field working in community development, Montague earned a master's degree in public health at the University of North Carolina to bring a more focused approach to his work. His journey last March began in Pakistan, where Montague flew on a United Nations' plane from Islamabad to Kabul. Once there, he was escorted by road on a six-hour mountainous trek to Bamiyan. Along the way, he counted at least 70 wrecked Russian tanks and personnel carriers--remnants of the Soviet war in Afghanistan. Once a huge tourist attraction because of its now-destroyed world-famous Buddha statues, Bamiyan was largely without water or electricity. Its only open hospital was run by expatriate physicians. Traveling on, Montague encountered the more mundane catastrophes of everyday life: destroyed homes and villages, wrecked bridges, bewildered Afghan refugees returning from Iran and Pakistan, and considerable proof that the country was not yet united, either politically or administratively. According to the CIA World Factbook, one out of five Afghan children dies before the age of 5. One in 12 Afghan women is said to die in childbirth, and the average Afghan life expectancy is 46. An ongoing drought had drawn down wells, aggravating Afghanistan's fundamental problem of securing potable water. Latrines were a foreign concept in the rural areas that Montague visited, and at least one-quarter of the health care visits tallied in the year 2000 by IbnSina sprang from water-related diseases. Diarrhea, worms, and typhoid run rampant. Montague's own constitution has been tested before;

the seasoned foreign aid specialist must regularly balance fastidiousness

with a touch of "what-the-hell." He accepted the indigenous

hospitality of his Bamiyan region hosts and got to work drafting

a modest proposal. The result is a collaborative concept paper outlining

how PFD and IbnSina might secure potable water for 36,000 people

in the Hazarajat region in central Afghanistan. With the preliminary

work complete, there is now the matter of securing funds. Efforts

are well under way, and Montague is moving on to yet another challenge--Nigeria.

"It's going to be a busy, busy time for me," he says.

Mike Doyle is a reporter in the Washington bureau of McClatchy Newspapers.

|

|

|