![]()

Winter

1999

Making Crime Pay

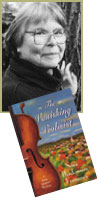

Sara Hoskinson Frommer / Publishing mystery novels was the last thing on Frommer's mind. With degrees in German from Oberlin and Brown, she taught for a while then worked in a series of jobs with a transportation economist, a team of ethnologists, and a student exchange program, all while bringing up two sons.

At Oberlin Frommer auditioned for the Gilbert and Sullivan Orchestra, but "fell short of the stiff competition," so she laid her viola aside for the next ten years. When her husband, Gabe Paul Frommer '57, took a position as a professor in the psychology department at Indiana University, she resharpened her musical skills and landed a spot with the Bloomington Symphony Orchestra. Her writing projects over the years included newsletters, brochures, and teachers' guides to instructional TV programs.

"I'd always thought I was a good writer until English comp at Oberlin," she says. "That class taught me the beginnings of what I needed to know. Now, I can't seem to help writing at the pace of a slug, although in the long gap between my first and second mystery novels I wrote 16 very short, very easy books for adults learning to read English. Five of those were mysteries. That was my most socially useful writing, and I was amazed to find that it paid the best of anything I've written."

The disappearance of Camila's violin made the national news.

The live broadcasts of the finals would be carried on public radio stations, though only the awards ceremony and concert would be televised at all. But this kind of news brought out the networks and put the competition on the front page of the Oliver paper, which until now had run only one routine story listing the countries from which the competitors came and the awards for which they were vying.

Much was made of the value of the missing violin, variously estimated from five hundred thousand to five million dollars. Joan wondered whether the press and broadcasters made up their figures as they went along.

"Such an instrument can't be replaced by money," said an impassioned official of the competition in a plea for the return of the violin. "It's a priceless treasure that should be played by a master musician, in this case the fine young Brazilian violinist from whose hands it was torn."

"Is that the way it happened, Mom?" Andrew asked at breakfast. "Did they come right up to her and tear it out of her hands?" With expertise born of experience, he caught the toast that flew out of their old toaster and began slathering jam on it. No wonder he had good hands for a Frisbee.

"Not according to Bruce, and he talked with her. He said she didn't even know it was missing until she opened the case to play it last night."

Marcia

Dutton Talley / Talley wrote her first mystery

in the fourth grade--a ghost town adventure with a

heroine named Lucy. "It was a dreadful Nancy Drew

rip-off," she says. "Later, I moved on to idolizing

Agatha Christie."

Marcia

Dutton Talley / Talley wrote her first mystery

in the fourth grade--a ghost town adventure with a

heroine named Lucy. "It was a dreadful Nancy Drew

rip-off," she says. "Later, I moved on to idolizing

Agatha Christie."

Talley and her husband, John Barry Talley '65, commute from Edgewater, Maryland, to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis where Marcia is the systems librarian and Barry is director of musical activities [see OAM March 1999]. They raised two daughters, including Laura Talley Geyer '90.

When her grade-school writing bug resurfaced in the early 1990s, Talley successfully submitted a 40-page manuscript--her "great southern literary novel"--to the Sewanee Writer's Conference at the University of the South. While there, she worked and dined with John Casey, Susan Minot, Horton Foote, and other writers she had always admired.

"The following summer I attended Bread Loaf (writers' conference), where I realized that if I wanted to be a writer, I'd have to stop talking about it and sit down and do it. Back home, I joined a local writers' group that helped me to see that I should be writing what I loved to read--mysteries." Her first novel, Sing It to Her Bones, won the coveted Malice Domestic Grant in 1998 and was selected by the Mystery Guild as a featured alternate this fall.

Even in that crippled

condition, I was still going 55 when I reached the

pond and realized with absolute certainty that,

barring a miracle, I wouldn't make it around the

curve. I pressed both feet on the brake pedal sending

the car fish-tailing across the center line. As

I pulled back into my lane, I was vaguely aware

that the dark van was still with me, but I was too

busy to think about much more than slowing the car

down. Hold on, Hannah! Here we go!

Shira

Rosan (S.J. Rozan) / "Writing is the hardest

thing I've done," says Rosan '72, who went to architecture

school after Oberlin "to be useful." She lives in

Greenwich Village and works as a senior associate

with a New York architecture firm specializing in

historical restoration and public buildings. She

occasionally manages to slip a bit of Oberlin folkways

and mores into her novels.

Shira

Rosan (S.J. Rozan) / "Writing is the hardest

thing I've done," says Rosan '72, who went to architecture

school after Oberlin "to be useful." She lives in

Greenwich Village and works as a senior associate

with a New York architecture firm specializing in

historical restoration and public buildings. She

occasionally manages to slip a bit of Oberlin folkways

and mores into her novels.

"I came out of Oberlin with a broad sweep of eclectic knowledge and a strong social conscience. Those two ideas--that all knowledge is equally valid and accessible, and that, once gained, knowledge should be used for something that helps someone--have informed my life since and are the basis of what and how I write," she says. "I write in the private detective form which allows--and demands--a lot of social commentary and large themes."

It's easy to get bogged down, Rosan admits, and she's been tempted to quit. "Every word matters, both in sound and meaning. But you can't let up, ever, even when there's not much reason to keep going. But nothing I've ever done is more satisfying when it works."

Rosan's series includes China Trade, Concourse, Mandarin Plaid, No Colder Place, A Bitter Feast, and the most recent, published last fall, Stone Quarry, all by St. Martin's Press. She's won the Shamus Award for Best Novel, the Anthony Award for Best Novel, and was nominated for the Edgar Award for Best Short Story, "Hoops." Rosan is the founder and moderator of a series of panels called Crime Writing and the American Imagination in New York.

Eve Colgate's mouth smiled as I put her drink on the scarred tabletop. Her eyes were doing work of their own. They were the palest eyes I'd ever seen, nearly colorless. They probed my face, my hands, swept over the room around us, followed my movements as I drank or lit a cigarette. When they met my eyes they paused, for a moment. They widened slightly, almost imperceptibly, and I thought for no reason of the way a dark room is revealed by a lightening flash, and how much darker it is, after that.

I smoked and let Eve Colgate's eyes play. I didn't meet them again. She took a breath, finally, and spoke, with the cautious manner of a carpenter using a distrusted tool.