In

ancient times, much of what we now call science was

the handmaiden of religion. In ancient Babylon, for

instance, only priests were permitted to study astronomy

and mathematics. Egyptians used geometry to build pyramids

and estimate the volume of water in their reservoirs.

But religion may have been a limiting factor. Neither

Egypt nor Babylon turned to science when mulling over

the nature of the universe. For that, they relied on

mythical explanations.

By

contrast, the Ionians, who had emigrated from Greece,

lived in a far more hostile environment and weren't

tethered by religious restrictions. Spurred by necessity

and freed from theocracy, the Ionians asked fundamental

questions about how the universe worked, according to

author James Burke in The Day the Universe Changed.

An early Ionian, Thales of Miletus, is credited with

using the constellation Ursa Minor as a point of reference

for navigation. With his students, Thales investigated

weather patterns, magnetism, condensation, and other

aspects of the world around them.

In the Middle Ages, as Europe spurned science, Moslem

scholars kept math, astronomy, and biology alive by

expanding upon the sciences of ancient Greece. In particular,

the Koran deemed biology as being close to God. Much

of this knowledge was preserved in great libraries built

by the growing Islamic empire in Spain, notably the

library established in the city of Toledo. The city

fell to Christian crusaders in 1085 and, soon after,

Christian monks translated the works into Latin. It

made sense that this task fell to the monks; until modern

times, only priests and the wealthy were sufficiently

educated for the job.

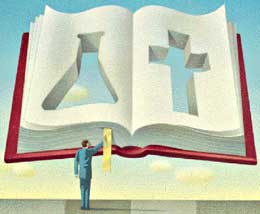

Later, in the mid-1700s, European philosophers argued

that science and religion were separate disciplines.

And yet, hostility didn't ensue. Enter Charles Darwin,

who shook segments of Christianity with a theory of

evolution that conflicted with the words of Genesis,

and science and religion were officially at odds. In

his 1874 bestseller, History of the Conflict Between

Science and Religion, medical school professor John

Draper fueled the belief that the Catholic Church was

the enemy of science, blocking progress "by the sword

and the stake." Adding to the controversy was Cornell

University President Dickson White's 1896 book The

History of the Warfare Between Science and Theology

in Christendom. As the clash of words continued,

perceptions changed, and the image of the two sides

being at war prevailed. So it has remained since the

latter part of the 19th century.

In reality, the issue is far from cut-and-dried. While

fundamentalist Christians in America continued to denounce

evolution, a 1996 conference sponsored by the Vatican

Observatory and the California-based Center for Theology

and the Natural Sciences concluded that evolution and

Christianity were compatible. "Religions have often supported

scientific endeavors," says Oberlin's Joyce McClure, assistant

professor of religion. "There's no inherent conflict between

the two disciplines, in my view."

But recent developments, particularly in genetics, are

already fostering new dissension. "Any form of genetic

manipulation of humans or animals has the potential for

causing a problem for religious persons," says McClure,

who teaches courses on ethical issues facing science.

But simple genetic manipulation may not be enough to set

off warning bells among Christians and Jews. Both traditions

have embraced the idea

that change--through evolution or through humanity's manipulation--is

part of the nature of things, she says. "There's nothing

new about that.

"The best candidates for a problem," McClure adds, "would

be things that reduce complexity. If it becomes possible--and

widespread--to select pre-embryos for intelligence or

physical strength, for instance, we would be selecting

one group over another, one that would have an advantage

over other segments of the population."

Ironically, the Big Bang theory, among the most complicated

and controversial theories to emerge in the 20th century,

wears well in many religious and non-religious circles.

"The idea that there was this event that brought space

and time into existence is appealing to people of faith,"

says McClure. "The idea of God as being eternal and

outside of time has been long-standing. And that concept

is not specific just to Christianity."

|