|

Issue Contents :: Feature :: In Defense of Books :: [ 1 2 ]

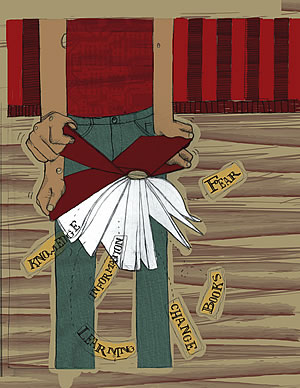

In Defense of Books

The Internet will not kill books, but it will radically change the terms of engagement.

By Robert Kuttner ’65, co-editor, The American Prospect

Illustration by Annie Olechowski

Who could forget rummaging the stacks of the College library, 4 x 6-inch note cards in hand, paging through book after book while researching a term paper on social contract theory or a lit essay on Mary Shelley’s presentation of the female figure? And who could forget the joy of serendipitous discovery when the perfect passage is finally found, not in a book tracked down from the card catalogue, but in one farther down the shelf?

In this Age of Google, says longtime editor Robert Kuttner ’65, libraries are more important than ever; they are the ungated hub of a learned community and a quiet refuge from cyberspace.

I’ve always thought of Oberlin as an oasis of insurgency in a complacent society. Libraries, on the other hand, have never struck me as particularly insurgent, and yet, when you think about it, libraries today are under siege in many ways.

The government wants libraries to snoop on people’s reading habits in the hope of catching terrorists. Libraries are asked to keep up with new and costly technologies at a time of budget cuts. Libraries are on the front lines of the defense of free expression. The whole question of what is freely in the public domain versus what is commercial property is being reargued and redefined.

Newspapers are filled with stories about the effort by Google to scan millions of library books into its massive database, a move opposed by publishers. Amazon proposes a different model, rather like iTunes, where readers can download whole books or extracts of books at a nickel a page. Most fundamentally, the proliferation of digital technology in the Internet age has led some to question whether bound books and journals and traditional libraries as physical places have a long-term future at all.

Thirteen years ago, when the Internet was in its infancy, the linguist Geoffrey Nunberg, in a very prescient essay titled The Future of the Book in the Age of Electronic Reproduction, wrote: “Reading what some people have to say about the future of knowledge in an electronic world, you sometimes have the picture of somebody holding all the books in the library by their spines and shaking them until the sentences fall out loose in space.”

I am here to defend books and libraries, particularly Oberlin’s. Every time I go into a library I marvel at the fact that it is an oasis, free from commercialization, where I can read a book or magazine, or check it out for free, and where a reference librarian is there to help me and not charge by the minute or the hour because we, as a society, have decided that dissemination of knowledge is a public good.

For more than a decade there has been a fascinating debate about the very future of libraries in the Internet age. There’s also been an enormous amount of debate about how this new technology is changing our heads: how we learn, how we think, how we relate to each other as a society.

In some respects the Internet is just an extension of the physical library. The Enlightenment dream of a universal encyclopedia reverberates in the promise of a universal and virtual library available from your laptop computer or Blackberry.

But some have very properly questioned what kind of learning habits the Internet and the virtual library induce, and where that leaves the physical library we all grew up with. There is also a threat, paradoxically, that the splendid universal access offered by the Internet will end up being commercialized and gated, and that the price we pay for an ostensibly free connection will be marketization and fragmentation, which in turn will destroy our sense of being a community of learning.

Without stretching the analogy too far, I think of Oberlin as both a physical community and a virtual community, one that prizes openness and inquiry and social values over purely commercial ones. My own values were shaped there. I became a kinder, more socially engaged person, and in the 40 years since I graduated, my deepest and dearest friendships have been with Oberlin people. There is a recognizable Oberlin ethic. And I doubt this would have been possible if Oberlin had been merely virtual.

So without being too much of a Luddite, I do think it’s worth pausing to explore what all this technology is doing to our heads and hearts, and to reassert the value of real, physical communities of learning. Social critics like Sven Birkerts warn that electronic communication, even when it entails reading a facsimile of a printed page on a computer screen, is more ephemeral and more conducive to short attention spans. If the primary way that students and young people use the Internet were merely as a universal library, this might be a plus; research and learning simply become more efficient. But there are also chat rooms and blogs and instant messaging and narcissistic personal websites and cyber porn and relentless surfing.

The Internet itself leads to attention deficit disorder. There is so much stuff just a click away that it’s hard to concentrate and stay focused—it’s so much more intoxicating to click and see what else is out there. Yet learning requires nothing so much as concentration and focus.

The web is a leveler, and that’s also a mixed blessing. On the one hand, unknown bloggers who are just as smart as New York Times reporters can command an instant following if they break important stories. But there’s also a ton of junk on the web. The ground rules aren’t clear, and people like me—editors who function as filters or certifiers whom the reader trusts to assign, select, verify, and edit articles—may be a dying breed as everyone gets to customize their own output and reading.

In deciding how the Internet will empower us as learners, we face some fateful choices as a society. On the one hand, the ethic of the Internet is that information should be free in both senses: free of charge and free to access, by all, to all. Interestingly, this exactly parallels the traditional ethic of the library. Yet because of new technology and the new ideology of commercialization, both kinds of freedom are at risk. After all, it’s only because of a series of happy accidents and the large role of the government in developing the Internet that the web evolved according to a kind common carrier model that is open on both ends. Anybody can post to it, and anybody can access it.

Next Page >>

|