Oberlin's first settlers realized that besides building a college, they needed to have a school for their own young children. In the first frame building, "Oberlin Hall," on the southwest corner of Main and College Streets, there was, a small space for Oberlin children to use as a school room. The first classes were taught by a young woman, Eliza Branch, who received $2.50 a week for her work. Miss Branch was a student at the College and boarded at Oberlin Hall. This two-story frame building also provided dining, sleeping, and classroom space for Oberlin students, plus office space and living quarters for professors and their families. The Hall also had a meeting room for town and college functions. As you can imagine, everyone was crowded together in Oberlin Hall.

By 1836, Oberlin villagers decided to have a school built just for their children. They also believed it would be better for the school to become part of the state's common, or public, school system rather than part of Oberlin College.

For $215, a one room schoolhouse built on the north east corner of Main and Lorain streets -- a little north of where First Church now stands. This small school measured 20 x 20 feet and had only one room. For many years it was the only school for children in Oberlin.

As you can imagine, schools were very different in those days. First, one teacher taught children of many different ages in each one room schoolhouse. Rough boards were used for benches and the floor. Later desks and chairs might be built so children would have a surface to write on. In the center of the room there was a pot belly stove to help keep everyone warm during cold days. In most school rooms of those days, there would be a globe of the world and a blackboard on which the teacher might write special sayings for the children to copy in their best handwriting. By copying proverbs like, "The early bird catches the worm," children of all ages learned how to ready, improve their handwriting, and how to get along in the world.

Schools then had very little paper for writing or drawing, but everyone managed pretty well with slates and chalk. Students read books called "primers." or "readers" The most popular readers were the McGuffey Readers, which were full of stories and poems that tried to teach the value of hard work, honesty, kindness, and other good qualities.

Each spring Oberlin third graders spend a day in the Little Red Schoolhouse after learning about Oberlin history. They and their teachers dress in old-fashioned clothes and carry lunch pails or baskets or wrap their lunches in cloth (brown paper bags had not yet been invented). At the school, they spend the day much as children did long ago, with stories to read in McGuffey readers and slates to write on. At noon and recess they play old-time games. It is a chance to feel like part of the past and learn about history.

Imagine you are a nine-year-old living in Oberlin in 1840. What would your day at the Little Red Schoolhouse have been like?

You'd have been up at six o'clock helping your father and mother with work that needed to be done. Boys would have helped fathers feed and bring water to the cows and horses. You would have gathered some split logs from the woodbox so that your mother would have enough wood to cook the family breakfast on the wood stove. Girls would have set the table, churned cream into butter, and gathered eggs from the chicken coop for the family's breakfast. As part of your chores, you might have rocked your baby brother in his cradle to keep him quiet so your mother could tend to cooking.

Once you'd eaten your porridge and scrambled eggs, you would have helped your mother pack your lunch in the tin pail you'd carry on your walk to school. There might be a bread and butter sandwich made with homemade bread, a piece of cornbread, and an apple.

You'd arrive about 8 o'clock, just before the teacher, Mr. Jeremiah Butler, stepped out to ring the school bell. You would line up outside the door, with the boys in one line and girls in another. Then you would march into the schoolroom. Girls would sit on one side of the room and boys on the other. Mr. Butler might have a warm fire glowing in the stove. You would hang your coat on a hook and set your lunch pails in a corner.

School would start with Mr. Butler reading a Bible passage, then you would kneel to say the Lord's Prayer. Then the school day would begin. The younger children would sit on the long bench in front of the teacher's tall desk. On his desk you'd see the school bell, a quill pen that he made from a goose feather, and a bottle of homemade ink. Next to his desk, you'd see a long switch, made from a tree. Usually he'd use the switch as a pointer to call attention to something he wrote on the blackboard. But sometimes he'd use the switch to awaken someone who had fallen asleep. You'd see a narrow stool in the corner holding a pointed cap labeled "Dunce". Sometimes when a student was lazy or didn't finish work, Mr. Butler would have the student sit on the stool and wear the cap.

Mr. Butler would have written the alphabet on the board. The young children would try to memorize it, backward as well as forward, by saying it over and over to themselves. The older children would be given a story to read in a McGuffey's Reader, perhaps the story about the boy who cried "wolf".

You'd soon be ready for geography class where you'd learn the names of the continents, oceans, rivers, mountains, and important cities. Mr. Butler might whirl the globe on his desk and ask for a student to locate the Atlantic Ocean or the Mississippi River. You'd raise your hand and hope you'd be chosen.

TIME FOR RECESS! You'd rush to put on your coat and get out to play. Outside, some of the boys might play a game of marbles. Other would play "Anty over the shanty" throwing a sock stuffed full of scraps of cloth over the school roof. Some of the girls might play "London Bridge is Falling Down" or "Drop the Handkerchief". All too soon you'd hear the bell ring and you'd all file inside. On your way in, each student could take a drink of water from a dipper that was placed in a pail of water by the door.

Arithmetic would be next. Mr. Butler would start the class with "Mental Arithmetic". The first problems would be easy one for the younger children: "What is three plus two? What is five minus two?" Gradually, the problems would get harder. "What is six time seven?" Finally, he would give a story problem to solve: "A farmer had 84 apples. He sold them to 7 people, each person buying an equal amount. How many apples did each customer buy?"

At last it would be time for lunch. You'd eat quickly and run outside again. You'd play more games and make a trip to the outhouse, until Mr. Butler rang the bell. On the way in, you'd stop for another drink from the dipper in the water pail. If one child had a cold or even chicken pox, everyone would probably get it. People had not yet learned that diseases could be spread this way.

After lunch you'd study grammar and spelling. The younger children would learn words from their primers. You'd try to read the words Mr. Butler wrote on the board and then practice spelling them by writing them on your slate. Older children might use Noah Webster's famous blue-backed spelling book. They'd learn to spell by syllables harder and harder words, like mechanic and chronology.

You might become part of a spelling bee. Mr. Butler would line groups of children in two rows. First, he'd start with easy words. If you spell the word correctly, you'd continue to stand in the line. If you missed, you'd sit down and whoever is next in the other line would try to spell the same word. Back and forth... The excitement grows as the words get harder and harder. Finally there would be only one child left standing to spell the last word and to receive everyone's cheers.

Reading aloud would be the last activity of the day. Students would start with primers and advance to more and more difficult readers. Younger readers could learn by listening to the older students read aloud.

Finally, at four o'clock, school would be over for the day. Mr. Butler would dismiss you after meeting with the class. Someone who has not done his work might have to stay after school to sweep the classroom. You might hear a warning not to get into a fight on the way home. Then Mr. Butler would tell you all to be sure to "make your manners to your parents" meaning a bow by boys and a curtsy by girls, "when you arrive home."

You'd walk home slowly. You'd be tired after a long eight hour school day. You might be thinking about the chores waiting for you at home: wood to chop, animals to feed and water, floors to sweep, a baby to tend, table to set, dishes to wash.

Mr. Butler would be tired too as he headed toward the home of the family that housed him for that week. He earned $18 a month plus room and board and laundry. He and his students would return six days a week for the three months that year that school was in session.

It was a busy life for everyone.

In just a few years the Little Red Schoolhouse became too small to hold all of Oberlin's young children. So wives of professors began teaching children in their homes, college buildings, or village shops. Finally, in 1851, a larger school was built on South Professor Street. The Little Red Schoolhouse was no longer needed.

This Little Red Schoolhouse has been moved many times since it was built. Today it is Oberlin's oldest building. Over the years it was used as a tailor's shop, a sign painter's shop, and a family home. By 1957, it looked as if the run-down, former schoolhouse would be torn down. But, a group of citizens believed it was an important part of Oberlin history. They raised money to buy and restore it so it would look life it did in the 1830s and 1840s. In 1968 it was moved to its present site, facing the Conservatory parking lot.

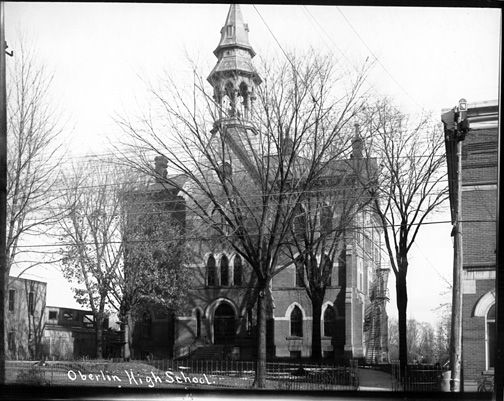

Other buildings in town have housed Oberlin's school children since that first schoolhouse. In 1874 the three-story Union High School opened on a downtown site where it still stands, known now as New Union Center for the Arts. The high school that was built on North Main Street in 1923 is now Langston Middle School. The current Prospect School is built on the same site as the original 1887 building. Eastwood School was built as an elementary school in 1955. The current Oberlin High School opened in 1965. The former Pleasant School on Pleasant Street is no longer being used by the school district.

In 1995, over 100 teachers, administrators, and other professional staff members, as well as over 50 support staff employees, in four school buildings serve the school children of the Oberlin School District. Schools in Oberlin have grown and changed in many ways since that first Little Red Schoolhouse opened in 1836.

School for Prospect School students today.is different in many ways from the Little Red Schoolhouse in 1840. In some ways the two schools are similar. Using categories from this list, compare and contrast the schools: then and now: school building, furniture, subjects, school day, lunch, recess, materials, (reading, writing, math, other?)

Oberlin: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow Home

Page | Table of Contents | ![]()

![]()