Imagine you were a nine-year-old slave working on a large plantation in the southern state of North Carolina in 1860. What would your life have been like?

First of all, your mother or father would have had little to say about what kind of work you did or where you did it. Those decisions were made by the Slave Driver who worked for the plantation owner, your Slave Master. Boys were given work to do outside: picking cotton, feeding farm animals, and tending to the fields. Girls usually cooked or cleaned inside the Slave Master's house or worked in small vegetable or flower gardens. You and your mother would have been owned by the Master. He and his Driver decided what you would eat, where you would sleep, and when and where you would work. Slave families were often divided when some members would be sold to other Slave Masters.

Also slave children could not attend schools. Even adult slaves were prohibited from learning how to read and write. A very few slaves secretly learned, but if they were caught, they were punished.

Your mother might have heard from other slaves that an "underground railroad" could help you get north to the free states of the United States and to Canada where you can live free. To get started, you would need to find your way in secret to the first stop, a house off the plantation. You and your mother might decide to risk running away, even though if either of you get caught, you would be whipped and made to work even harder. You would have to travel at night so you would not be seen. You could use the North Star to guide your way.

On a clear dark night, you would need to dress in dark clothes and stuff whatever food and other clothes you had into a small bundle you could carry. You would have to sneak off the plantation and find the house that was described, with only the stars to guide you.

With the eastern sky just getting light, you would knock lightly on the back door of that house. Whoever opened the door would direct you to a hiding place, perhaps into a kitchen cupboard that hides a door to a hidden stairway in the cellar or attic. Other African-American slaves who are running away might be hiding there too.

You would now be on a secret, or underground, transportation system: the Underground Railroad. But there would be no tracks or trains on this railroad. You would travel at night on roads and pathways to certain houses and farms called "stations" located every ten to twenty miles north, all the way to Canada. These stations would be hiding places to rest and sleep until dark when it would be safer to travel. The kind "station masters" would provide food and safety during the day for the "passengers" and would give directions to the next "station" if there were no "conductor" to lead them. Some station masters risked their own safety even further by hiding their "passengers" in wagons or boats to carry them north.

You would have to be strong and smart to travel so many miles from station to station, and, with the help of others who believed that slavery was wrong, you could complete this long trip to freedom.

Imagine you were a nine-year-old runaway slave who after three long weeks of walking, running, and hiding reached the town of Oberlin, Ohio. What would you find there?

You would be tired and sore, but excited to be in a state without slavery. Also Oberlin was near a big lake, Lake Erie, that divided the United States and Canada. Canada had no Fugitive Slave Law like the U.S. In Canada, you could not be hunted down and returned to your Slave Master. So if you could get across or part way around the lake to its northern shore, you would be free.

You might be told to walk along the dirt road into Oberlin, until you came to a huge church. You could find the Bardwell House, your next station, by turning east at the church, walking two more blocks, and looking for a low white house with a peaked roof on the north side of the road. The single candle burning in the one front, upstairs window would be the final clue. The woman who greeted you would take you to her kitchen to wash up and get warm by the fire in the fireplace. She would show you the small hidden room in the attic where you could sleep in safety.

The Bardwell House, built in 1846, was an Oberlin station on the Underground Railroad. It now sits on a different site at 181 E. Lorain St.

You could stay at the Bardwells for a week or more to regain your strength. You would not have to hide during the day because there were so many free blacks in Oberlin. Also the people of Oberlin would risk their freedom to protect yours. In 1858 black and white Oberlinians rescued runaway slave John Price from slave catchers who had taken him, by force, from Oberlin to Wellington. The slave catchers planned to return him to his southern owners. But John Price was whisked back to Oberlin and sent on his way to Canada. Most Oberlinians did not agree with the Fugitive Slave Law and many were abolitionists who worked to end slavery anywhere in the United States.

If you walked around Oberlin, you'd see all the children in school together, learning to read and write. The school in Oberlin was open to all children, no matter what color of skin they had. There was even a school called the "Liberty School" where grown-ups could learn to read and write.

You would have found out that black and white hands worked together to build First Church. A lot of African-Americans in Oberlin were skilled carpenters and builders.

You would have found that black and white people attend this church, and sit right along side each other listening to the famous white minister, Charles Finney, preach. Black Oberlinians could also choose to worship together, at the Liberty School, or outside if the weather was nice, listening to black preachers.

You would have found that "Patterson's Corner", a big brick building on the southeast corner of Main and Lorain Streets, held the grocery store owned by Henry Patterson, an African-American. Several of his older children attended Oberlin College.

You would have found out that some big houses in Oberlin belonged to black families. Wilson Bruce Evans, a cabinet maker, built his Mill Street house himself, even hand-carving the beautiful stairwell and banister from walnut. Across the street from the Evans house, you'd have seen harness-maker John Scott's house. Both the Scott and Evans families came to Oberlin as freed slaves from North Carolina.

You would have seen the large house on east College Street that

was owned by the attorney John Mercer Langston. Mr. Langston was one

of only a few black lawyers in the country, the first in Ohio. He

helped Oberlin by paying for the expenses of running the underground

railroad, by being a member of the school board, by providing

scholarships for black students at Oberlin College, and, with his

wife Caroline, by taking in both black and white boarders from the

college.

You might want to stay longer in Oberlin but it wouldn't be completely safe until the laws of the United States changed. You would probably want to continue on to Canada, perhaps hoping to return some day when you could be free to call Oberlin "home".

The Underground Railroad really existed. Between 1830 and 1860 about 50,000 slaves escaped. The Underground Railroad was especially active in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Oberlin was Station 99 in this secret escape system.

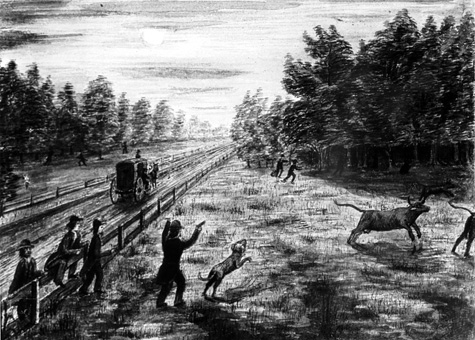

Oberlin received attention nation-wide in 1858 and 1859 for its part in the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue. John Price had been living in Oberlin for almost two years after escaping from slavery. A U.S. Marshall with the slave catchers had captured John Price and taken him by buggy to Wellington to wait for the train to Columbus. The news of the capture spread rapidly in Oberlin and a crowd of hundreds, black and white, started on the road to Wellington. They were determined to keep John Price from being taken back to slavery.

When they saw the crowd, the U.S. Marshall and the slave catchers took John Price up to a small room on the third floor of the hotel and locked the door. Some men from Oberlin went into the hotel, rushed John Price down the stairs, and carried him in a buggy back to Oberlin. For several days he was hidden in the home of the college president, President Fairchild, and then was taken to Canada where he could be free.

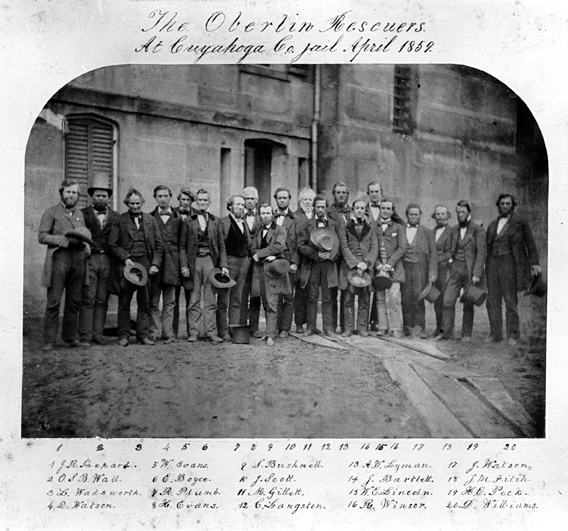

The people who were most important in the rescue of John Price broke the Fugitive Slave Law, the federal law that said an escaped slave had to be returned to his owner. They had broken a law that they believed was wrong and they were willing to risk punishment. Thirty-seven of them were charged. Twenty-one were sent to Cleveland for trial and kept in jail for up to 84 days.

While in jail, the prisoners were visited by many people, including the 400 children from the Church Sabbath (Sunday) School who came to see their superintendent. The men in jail even published a newspaper called "The Rescuer". Charles Langston, one of the black rescuers who had been arrested, gave a strong speech to the judge about the evilness of slavery and the need for freedom for all men and women. The prisoners knew that by staying in jail and letting the whole country hear about the evils of slavery, they could help the abolitionist cause.

Click

on photo to enlarge.

Click

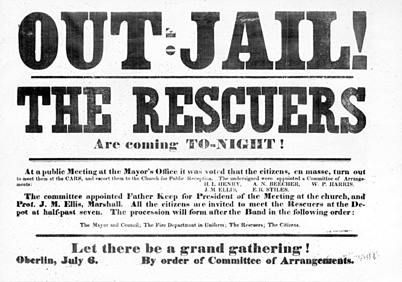

on photo to enlarge.When the men were released, they returned to Oberlin on the train. A huge crowd had gathered at the station on Main Street. As the former prisoners got off the train, guns were shot off, music was played and everyone cheered wildly. Then they all marched through the streets to the Church where all the rescuers made speeches about what had happened as part of the celebration.

Their belief in freedom for all people had gotten them arrested. But they were rewarded when on New Year's Day, 1863, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States signed a new law, the Emancipation Proclamation, that ended all slavery in this country.

The Underground Railroad would no longer be needed. All Oberlinians could live free together.

In January 1980, nine black Oberlin College students donned draw-string burlap pants, calico dresses, bright bandanas, and wool scarves and set out on foot from Greensburg, Kentucky, to Oberlin -- a 33 day trip of 420 miles. They walked at night in Kentucky and during the day in Ohio, slept in barns and unheated houses, and ate grits, corn fritters, yams, and oatmeal. They were simulating a slave escape along the underground railroad so they could rediscover the experience of runaway slaves. Their daring project brought to our attention that the challenges faced by these brave freedom-seeking people have not been forgotten.

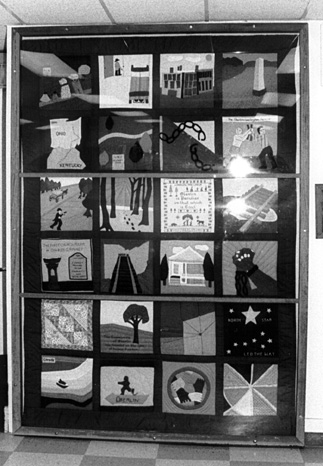

Today

Oberlinians continue to honor those who risked their well-being

escaping from slavery, those who helped others to escape and to

remain free, and those who worked to end slavery. Oberlinians today

visit the Underground Railroad Sculpture outside Talcott Hall, the

Underground Railroad Monument at Westwood Cemetery, the Underground

Railroad Quilt at the Community Center, and the monuments honoring

the Oberlin-Wellington rescuers and the Oberlinians who died in John

Brown's raid on Harpers

Ferry at Martin Luther King Park.

Today

Oberlinians continue to honor those who risked their well-being

escaping from slavery, those who helped others to escape and to

remain free, and those who worked to end slavery. Oberlinians today

visit the Underground Railroad Sculpture outside Talcott Hall, the

Underground Railroad Monument at Westwood Cemetery, the Underground

Railroad Quilt at the Community Center, and the monuments honoring

the Oberlin-Wellington rescuers and the Oberlinians who died in John

Brown's raid on Harpers

Ferry at Martin Luther King Park.

We take pride in Oberlin's important role in history.

Design a quilt square that could be added to Oberlin's Underground Railroad Quilt. Use words to tell about your design.

Oberlin: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow Home

Page | Table of Contents | ![]()

![]()