|

|

As the end of June approaches each year, a sense of calm anticipation settles over me. This is different from what I feel over test scores or music recitals. June anticipation is not apprehensive; it is purely exhilarating. My wait will finally be over when tiny white butterfly eggs appear on the milkweed plants outside.

From June to September, monarch butterflies grace the northern United States with their presence. During the rest of the year, they are traveling the 1,800 miles from my home in West Virginia to Angangueo, Mexico, or are overwintering there on fir trees. Of the millions of butterflies that begin this yearly migration, only a handful of their descendants will end up in my bug containers. So, I sometimes ask myself: Why do I spend hours in milkweed meadows around the country gathering eggs and caterpillars? Why do I interfere in this incredible natural cycle?

One of the answers is clearly selfish. Quite simply, monarchs are beautiful. I never fail to be in awe of a tiny, ribbed egg on a leaf or of a minuscule larva eating its way out of an egg--vivid black and yellow stripes warning of its poison--or of a caterpillar hanging itself carefully by silken threads and shedding its skin to reveal an emerald green chrysalis with shimmering dots of gold, or of a hatching monarch butterfly drying its wings. A butterfly emerges from inside the shell of a chrysalis, which forms under the skin of a caterpillar. The transformation from crawling, voracious eater into a transient flash of orange and black wings is astonishing.

More importantly, I am helping them. In the wild, many monarchs never make it to adulthood. I have carefully observed eggs and caterpillars left outside and found that few survive predators, winds, and rains. My own success rate is over 95 percent; in my butterfly career over the past 13 years, I have released more than 500 adults. Some of the best milkweed grows around the edges of cornfields. Milkweed dusted by pollen from genetically engineered corn may be deadly to the caterpillars, so I am also saving lives when I collect monarchs from these plants.

I have taken hatching chrysalises to school (a chrysalis turns purple when the butterfly is ready to emerge) and have given them to my younger sister to show to her classmates. This never fails to produce many questions and much excitement from the children, hopefully ensuring their future respect for the environment.

What was once a childhood fascination has grown into a lifelong passion. I assure myself that what I am doing is right when I watch something so apparently fragile and ephemeral spread its wings for the first time and embark on a journey I cannot begin to fathom. And every time I see a monarch pass overhead, I wonder if it is one of mine.

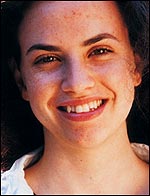

SHAMA CASH-GOLDWASSER

Morgantown, West Virginia

Morgantown, West Virginia