by KRISTIN OHLSON

Illustrations for OAM by Lynn Bennett

Illustrations for OAM by Lynn Bennett

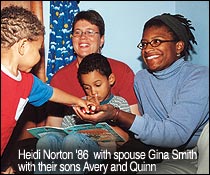

Census 2000 data imply that marriage is waning. But the figures don't tell the full story. Exchanging vows is still the path of choice for many couples--those with and without the legal right to do so.When Gina Smith Boarded the plane with her son, Avery, in her arms, everyone cooed. Flight attendants, first-class passengers, long rows of people in economy, even those who would ordinarily wince at the sight of an infant in their cabin smiled at this lovely African-American mother. She was so obviously delighted with the tiny, brown baby who was a perfect miniature of herself. • But soon the lingering smiles turned into curious stares. Passengers whipped their heads around for a second and third look as Heidi Norton, the tall white woman who had taken the seat next to Gina, reached for the baby and prepared to nurse him as the plane began its ascent. • "You could tell by the looks on their faces that they were thinking, 'Wait a minute--that's not your baby,'" laughs Norton '86, Smith's partner for 11 years and Avery's other mother. "But it wasn't really a negative response, just a confused one. In fact, we've never had anything negative happen."

Aside

from moments like this, and the one obvious divergence from the norm, Smith

and Norton's life together is a cameo of the traditional nuclear family--a

glowing cameo, an emblem of the best of that life. Norton is the biological

mother of Avery, now 5 years old, and his 18-month-old brother, Quinn, but

there is a serendipitous family resemblance between mothers and sons. Norton

and Smith wanted the boys to look as much like the two of them as possible,

so they selected an African-American sperm donor who just happened to have

features like Smith's.

Aside

from moments like this, and the one obvious divergence from the norm, Smith

and Norton's life together is a cameo of the traditional nuclear family--a

glowing cameo, an emblem of the best of that life. Norton is the biological

mother of Avery, now 5 years old, and his 18-month-old brother, Quinn, but

there is a serendipitous family resemblance between mothers and sons. Norton

and Smith wanted the boys to look as much like the two of them as possible,

so they selected an African-American sperm donor who just happened to have

features like Smith's. The family lives in a small ranch house on a quiet street in Northampton, Massachusetts, where their days progress in a pleasant blur. Mornings begin at 6:30 when the boys awake. There's lots to do before they are whisked off to day care: books to read, a science project to check (currently, white carnations in cups of colored liquid), Avery's asthma treatment to administer, breakfast, clothes. Nights are another swirl of play and work. Sometimes the four of them eat alone, first holding hands in thanksgiving before Avery caps the moment with "I'm thankful that God loves our family." Sometimes they have dinner with friends. Sometimes the four of them attend a Quaker meeting event or practice with a local gospel choir. Sometimes Norton and Smith have an adult dinner by themselves once the children are in bed.

Their life is so comfortable--surrounded by loving friends, an accepting community, and doting relatives--that Norton and Smith have decided to court the kind of harsh scrutiny that might wither less-sturdy families. They have joined a historic lawsuit with six other same-sex couples against the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, charging that the state's refusal to grant them a marriage license violates the Massachusetts Constitution. The lawsuit is represented by Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders, the same organization that fought for the right of gays and lesbians to enter into civil unions in Vermont.

"We joined the lawsuit because fairness and equality are important to us," says Norton, who is the law program director at the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. "The lawsuit needed people who were willing to put their lives out there for inspection. We thought that if we couldn't do it, who could?"

It is an interesting time for a lesbian couple to be suing for the right to marry. The Massachusetts state legislature is considering a Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA)--a version of the 1996 federal act that dictates that the word marriage means only a legal union between one man and one woman, and that the word spouse refers only to a person of the opposite sex who is a husband or wife. Given yet another attack on gays and lesbians in the name of marriage, some might wonder why couples even bother with the legalities.

TO WED OR NOT TO WED

But what of couples who do have the legal right to marry? Public acceptance of cohabitation and premarital sex are at an all-time high, and media spasms over Census 2000 data give the impression that very few couples are marching down the aisle these days. The Christian Science Monitor, in a May 16 article, sings a typical lament in its opening paragraph: "The 2000 Census has had a number of surprises--but none (so far) more socially significant than that of a 71 percent increase over the past decade in the number of unmarried partners living together. Married-couple households grew by just 7 percent."

But such a paragraph makes better drama than analysis. In fact, researchers don't seem to be at all shocked by the steep rise in the cohabitation rate and the relatively smaller blip in the marriage rate: these are a continuation of trends away from the traditional nuclear family that began in the 1960s. Translated to numbers, the 71 percent loses some of its punch. There were 5.5 million unmarried-partner households in 2000 (including 472,289 same-sex pairs)--up from 3.2 million in 1990. Married-couple households had a larger increase: from 50.7 million in 1990 to 54.5 million in 2000. Since even the same numerical changes in small populations create bigger percentages than in larger populations, the implication that more people are choosing cohabitation over marriage is simply wrong.

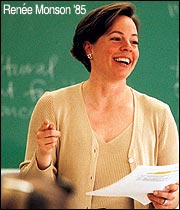

In any

case, the rise in cohabitation doesn't necessarily mean that couples are

choosing to live together instead of marrying; for many, playing house is

simply the first step. "Cohabitation is now the norm in terms of how people

enter marriage," says Renée Monson '85, an assistant professor of

sociology at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. "About half of all first

marriages and two-thirds of second marriages begin with cohabitation. It's

not the only path to marriage these days, but it is the typical path."

In any

case, the rise in cohabitation doesn't necessarily mean that couples are

choosing to live together instead of marrying; for many, playing house is

simply the first step. "Cohabitation is now the norm in terms of how people

enter marriage," says Renée Monson '85, an assistant professor of

sociology at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. "About half of all first

marriages and two-thirds of second marriages begin with cohabitation. It's

not the only path to marriage these days, but it is the typical path." So marriage isn't dead, but it's certainly safe to say that it's in flux--and still regarded with caution by couples who see plenty of bad marriages and messy divorces in their own worlds. But for gays and lesbians excluded from the right to wed, the benefits of marriage seem enormous. Norton and Smith have already had a commitment ceremony to declare their love to the world. But, as lawyers, they know that their formal declaration, plus all the paperwork they can muster, won't secure the legal protections and benefits of marriage. This basic inequality has been sharpened by the federal Defense of Marriage Act, as well as state-sponsored iterations of it. Often called "Super DOMAs," some of these proposed state laws attempt to block domestic partnerships, inheritance, adoption, and even the right to visit a partner in the hospital.

Then there are the financial benefits of matrimony, conferred in myriad ways from insurance to health-club memberships to train tickets. Even heterosexual couples who eschew marriage for one reason or another discover themselves paying the costs. Andrea Ayvazian '73 is dean of religious life at Mount Holyoke College. As an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ, she marries dozens of same-sex couples every year. Seventeen years ago, she and her partner, Michael Klare--both activists for social and political change--decided to defer their own marriage vows until gay and lesbian couples could be united with the same rights and rewards as heterosexuals.

"When we connected as a couple, it seemed clear to us that we should take the next step--by not taking the next step," Ayvazian says. "It is a very expensive witness, however. Michael carries a family health insurance plan through work to cover our son, and I have to carry another plan. We do not take family discounts anywhere unless the place also offers them to gay and lesbian families. Each month, our decision not to marry costs us hundreds of dollars."