The Last Word

Civil Disobedience

Although never a leader, she could run today on the Freak and Freedom party.

The

flyer stood out among the layers of posters crowding

the bulletin board: "THE Student Government is YOUR Student Government--Vote

for the FREAK AND FREEDOM PARTY." A photograph at the bottom showed two

men with big hair; one had wire-rimmed glasses. The other, I knew, was

a freshman--as was I--and he and this upperclassman whom he had somehow

befriended were radicals. I, however, was a high-school nerd masquerading

as a college student. It was 1969, and the war was hot. Now, more than

30 years later, when I tell my students that "the war was hot," they knit

their brows. Which war was that?

The

flyer stood out among the layers of posters crowding

the bulletin board: "THE Student Government is YOUR Student Government--Vote

for the FREAK AND FREEDOM PARTY." A photograph at the bottom showed two

men with big hair; one had wire-rimmed glasses. The other, I knew, was

a freshman--as was I--and he and this upperclassman whom he had somehow

befriended were radicals. I, however, was a high-school nerd masquerading

as a college student. It was 1969, and the war was hot. Now, more than

30 years later, when I tell my students that "the war was hot," they knit

their brows. Which war was that?

I

came to Oberlin with a footlocker, as if I were going away to summer camp,

and carried purses that matched my belts and shoes for the entire first

semester. Still, I was affected by the growing agitation surrounding the

Vietnam War. By spring semester, even I could not stand on the shore as

the river of anti-war activism rose with great swells. Eventually, it

carried us all downstream.

On

May 4, 1970, the shots fired at Kent State killed four young people and

altered the lives of thousands more. When those students died on the pavement,

who can say how many people were catapulted into taking action against

the war? I know I was. I donned my blue and red bell-bottoms, climbed

into the back of a Washington, DC,-bound U-Haul filled with hay, and marched

in my first demonstration.

During the next three years I found ways to protest the war, but I was never in the forefront and never quite with it. I was near the stage in Finney Chapel when Jerry Rubin literally burst from the wings, screaming, and then tore off his wig and twirled it on his finger. But I didn't know the lyrics everyone else seemed to know when, at the close of the evening, a student with long straight hair and a guitar took to the stage and led the crowd in singing mournful folk songs. I marched in many rallies, but never in the lead, and I often wondered how those students up front invented such perfect slogans for their bannered sheets. I abandoned all grades and took every one of my courses credit/no entry so I would have more time to "get involved." Still, I suffered through endless hours of Spanish, English, and biology homework, never quite as free as those radicals who never seemed to study, yet still earned good grades.

The war raged on, and the protests continued. Again, I was involved, but never a leader. Looking back, I realize that the political activism at Oberlin was the crucible through which I forged my life's direction and purpose. Although some of the fury overwhelmed me and some of the slogans confused me, I absorbed it all. The underlying values--those of peace, freedom, and equity--left a lasting imprint.

That imprint was evident last spring, when I gathered with two dozen people of faith and knelt in prayer in front of the Department of Energy in our nation's capital. Our songs, prayers, and laments to save and honor all Creation were heartfelt and powerful. Even our arresting officers stood back for the longest time--quiet, respectful, restrained. When we sang "Amazing Grace" and broke into a faltering harmony, one policewoman seemed to be singing along.

The day before our arrest, I had prepared the group for the action with a three-hour nonviolence training workshop. That night, on a cot in a church basement, I lay awake, thinking about past arrests and jail time. There have been frightening moments and uncomfortable quarters and painful separations, but always a sense that my commitments and behaviors were aligned.

Some of my students at Mount Holyoke know that I have spent time in jail for civil disobedience. The college administration knows that I am a war tax resister, and that I withhold part of my federal income tax annually. Friends and family know that Michael and I have deferred our marriage for 17 years, waiting until gay men and lesbians can be legally married. These and other decisions have helped me live a life, which although filled with contradictions and compromises, reflects some of the principals I learned at Oberlin.

Now, at age 50, I could run on the "Freak and Freedom" party. The photo attached to the flyer would show a middle-aged woman, lined, graying, and plump, holding a banner and wearing a grin. *

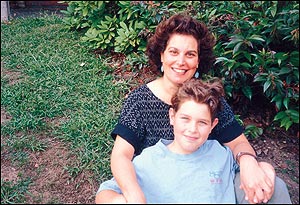

Rev.

Andrea Ayvazian, an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ,

is dean of religious life at Mount Holyoke College. She lives in Northampton,

Massachusetts, with her partner, Michael Klare, and their son, Sasha.