Marriage:

For Better? Or Worse?... Continued

Marriage:

For Better? Or Worse?... Continued ECONOMIC INCENTIVES

Granted there are alternatives to the nuptial path. But some researchers say there is evidence that marriage is on the rebound. Census watchers were anticipating a continued rise in non-family households--a category that includes unmarried partners without children, singles, and groups of unrelated adults--as a percentage of all households. However, the 2000 numbers held a surprise.

"The rate of this change is decreasing," says Tavia Simmons, family demographer for the U.S. Census Bureau. "It's slowing down, and that fits in with other trends we've seen, such as the leveling off of both the divorce rate and the rate of premarital births. But these trends are complicated: you can see different stories depending on which numbers you look at."

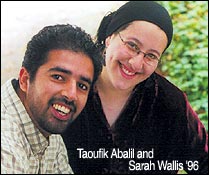

Sarah Wallis

'96, a publications designer for the Hesperian Foundation in San Francisco,

has been married for four years and knows at least four Oberlin classmates

who have married in the last few months. "It must be something in the water,"

she says. "Suddenly everyone I know is either getting married or is buying

an incredibly tacky bridesmaid's dress. There seems to be an epidemic of

weddings, despite all the dire predictions about the fate of the institution

of marriage."

Sarah Wallis

'96, a publications designer for the Hesperian Foundation in San Francisco,

has been married for four years and knows at least four Oberlin classmates

who have married in the last few months. "It must be something in the water,"

she says. "Suddenly everyone I know is either getting married or is buying

an incredibly tacky bridesmaid's dress. There seems to be an epidemic of

weddings, despite all the dire predictions about the fate of the institution

of marriage." As with any social phenomenon, the many reasons why people marry are complex and controversial. Certainly, welfare changes have had an impact. Wendell Primus, the director of income security at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, suggests that more former welfare mothers are in the workforce meeting marriageable men, and that men who conceive children out of wedlock are more likely today to be involved in the child support system than they were 10 years ago, providing an incentive to take the implications of fatherhood more seriously.

Monson, the sociology professor, points out that mothers have traditionally had just three means of supporting their children--men, the market, and the state. With welfare reform pushing women into a market that offers only the well-educated a livable wage, she explains, more are forced to rely on marriage.

The "I do" incentive is also steeped in certain cultures. Primus points to church-based initiatives in the African-American community that push responsible parenting and marriage. Monson says that pro-marriage paeans from presidents Clinton and Bush have permeated the culture. And Jaclyn Geller '85 insists that American society is loaded with pressures to marry, especially for women: from the "blockbuster wedding"--which can easily cost $150,000 in New York City--to television shows like "Ally McBeal," which portray smart, successful women desperate to hook a man.

"We live in the era of the couple, in a way that our ancestors did not," says Geller, a PhD candidate who teaches English and writing at New York University. Her new book, Here Comes the Bride: Women, Weddings, and the Marriage Mystique, critiques the continuing allure of matrimony. "When people are not part of a romantic couple, they are perceived as fragmentary," she says. "When they get married, they have an incredible sense of ease: it's as if a trapdoor opens over their heads and a cavalcade of money and goods comes down. That's a fairly new phenomenon."

As Geller implies, much of what propels people into marriage is not based on emotions, but economics. Some researchers blame economics for the drop in marriage rates that began in the 1960s: wages for men began a long, steady decline throughout the decade. Men began to seek marriage at a later age; they also became less-sturdy financial pillars.

As women began to pursue careers in greater numbers, the economic push-me/pull-you effect became more complex. As their incomes increased, women became more attractive partners for men. On the other hand, women, especially well-educated, high earners, had less need for marriage and became more particular about their prospective husbands. Some marriages shattered under the pressure of what sociologist Arlie Hochschild calls the "stalled revolution:" while wives entered the workforce in droves and contributed substantially to household incomes, there wasn't an equivalent shift in household responsibilities taken on by husbands.

But just as these glacial economic trends pushed people away from marriage in past decades, they're likely part of the force surrounding the new trends. After all, many people agree that it takes two incomes to maintain a household these days. It's possible that as partners become more mutually dependent, they view marriage, civil unions, and other legal partnerships as a better deal. It's certainly tough to go it alone with children. In fact, data collected by Elizabeth Warren of the Harvard Law School suggests that divorced women with children are filing for bankruptcy in increasing numbers and more frequently than any other group.

Still, it seems too reductive to corral all these new marriages into sociological and economic trends. This is still about love and commitment in its many-splendored, many-surprising forms. And while Geller's book adds to the debate about coupling by arguing that one need not do it--there are other ways to connect--what most people want, at some point or another, is a special connection to another person.

"Any marriage these days really is a triumph of optimism over experience," says Wallis, whose parents divorced when she was 12. "It carries so much baggage: that marriage is a relic of the '50s, that it's a tool of the patriarchy for keeping women down, that it's a government intrusion into personal relationships. But to me, it's about stating to the world--and to each other--that the person you love is now family to you. To me that's a basic human need."

One of the flaws of the Census is its definition of a family. It does not consider unmarried partners without children to be family, though they might think of themselves that way. It will not consider same-sex partners like Norton and Smith to be married, no matter what they write on a form. And the government is not on the side of love and commitment when it comes to same-sex couples.

Conservatives argue that the DOMA bolsters the institution of marriage, but the irony is that many of the same-sex couples excluded by this law are the nation's most unabashed supporters of matrimony. Perhaps conservatives would see their much-desired surge in marriage rates if they'd allow anyone who's eager to plight their troth--Norton, Smith, and the thousands of men and women like them--to go ahead and do so.

"I see how the government defines us," says Oberlin sociology professor Daphne John, who has a lesbian partner. "But we have the kind of caring and trust and long-term plans that married couples do. That's what I think an American family is."