|

The

Organizer The

Organizer

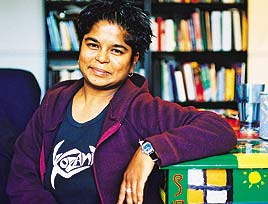

Grassroots movements are nothing new for Kirti Baranwal '98. While

thousands of people demonstrate against international financial

bodies that force cuts in social services overseas, Baranwal fights

similar cutbacks in Los Angeles, starting with the middle-school

classroom where she teaches math, science, and art. Some L.A. classrooms

are crammed with 70 students, and many of Baranwal's pupils arrive

late to school, having been bypassed by two or three overstuffed

public buses in their low-income neighborhoods.

Anti-corporate globalization activists talk

at length about needing to build local, community-based movements,

but Baranwal has been at it for years. Environmental studies classes

at Oberlin taught her the history of environmental racism and that

it can devastate working-class communities of color; they didn't

cover the practicalities of how citizens could fight the placement

of polluting industries in their neighborhoods.

Her interest was not only academic; it was rooted

in her upbringing and identity. "As an Asian American woman

from a working-class background who had the privilege to get to

college, it was very important for me to ask, 'How do I put my skills

to work, changing the material conditions for people in working-class

communities of color?'" she says.

She eventually found some answers at Oberlin, where

Eric Mann, director of the Labor-Community Strategy Center (LCSC)

in Los Angeles, spoke once about the multiracial coalitions he had

worked with to fight environmental racism and transportation inequities--all

with an underlying analysis of how institutional power works across

the board.

As Mann spoke, Baranwal's future materialized. "I

was floored," she says. She took a leave of absence from Oberlin

and spent seven months at the LCSC's School for Organizing, where

she studied a philosophy of community organizing that emphasizes

thoughtful strategy in combination with action. "You have to

have a theory about how to change things," she says. "It's

not just about feeling good about yourself. The goal is to see if

we can build a multiracial, antiracist, social movement that can

really win things."

Returning to Oberlin with a new focus and purpose,

she joined Third World Co-op and moved into Third World House, where

she later served as an RC. She brought speakers to campus and worked

on building a sense of community for students of color and from

low-income backgrounds.

After graduating, she moved back to L.A. to work with

the Bus Riders Union, the flagship project of the LCSC. The organization

was on a roll, having recently celebrated a high-profile victory

against the Los Angeles Mass Transit Authority. A federal judge

had ordered the MTA to reduce overcrowding on the buses, implement

reduced-fare passes, and introduce less-polluting natural gas buses

onto the fleet. The MTA would appeal the decision several times

over the next five years, but the Bus Riders Union, employing a

mix of legal avenues and street action, repeatedly came out on top.

As a full-time organizer, Baranwal was an exception

among her college friends. Many of the Obies she knew from Third

World House and Co-op had graduated under onerous loads of debt

and had moved home with their parents. For them, the life of an

organizer, with its 60-hour weeks and minimum-wage salary, was not

an option. Other alumni, including those from low-income backgrounds,

preferred taking their activist skills and resources back to their

hometowns.

After two years as a staff organizer with the Bus

Riders Union, Baranwal switched to teaching middle school. She organizes

after-hours with the Coalition for Education Justice, a group of

L.A. teachers, parents, and students pushing for smaller class sizes,

bilingual education, and an end to high-stakes testing and police

presence at schools. And she still loves the way a skillful organizer,

armed with compassion and good theory, can use a single issue to

get people talking about how institutional racism operates, how

to challenge government and business leaders, and how the civil

rights struggles of the past 50 years are all interconnected.

"Fundamentally, my organizing is a work of love,"

she says. "It helps me acknowledge how much beauty and strength

there are within communities of color and the working class. It

gives me peace in a world where there is violence in many forms.

And, in this society, which creates very negative and horrible things,

it helps me to create beautiful things."

Page 1 |

2 | 3 | 4

| 5 | 6

of A New Age of Activism

|