|

|

|

Obies and the Peace Corps: A Longtime Engagement |

||

An excerpt from Kennedy's inaugural address captures well the essence of the Peace Corps' philosophy: "To those people in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves." Oberlin College has had a strong relationship with the Peace Corps since the earliest days of the organization's existence. Between 1963 and 1967 the Peace Corps located one of its first regional recruiting and training centers on Oberlin's campus, often hiring faculty members and students to assist in administrative and educational tasks. Year in and year out, Oberlin's graduates volunteer for service in the Corps at a rate unprecedented for a school its size. Currently Oberlin ranks sixth nationally among smaller colleges and universities, out-volunteering institutions such as Dartmouth, Reed, and Johns Hopkins University. During any given year there are about 20 Oberlinians stationed with the Peace Corps at every corner of the globe, involved in almost every imaginable capacity. Time spent with the Corps can significantly change the future lives and careers of its volunteers, such as Laura Wendell '90, founder of the World Library Partnership, an organization inspired by her service in Togo, West Africa. Although the average age of volunteers, 30, has remained fairly constant since the Peace Corps' inception, an ever-increasing number of retirees are opting to get involved. Lawrence Siddall '52, who served two years teaching in Poland at the age of 67, is a case in point. Volunteers of any age are capable of making meaningful contributions to the cause, and the Peace Corps operates in many locales, performing such a wide array of functions, that anyone sharing in its vision and dedication to service is welcome and needed. Oberlinians have met and will continue to meet this challenge, whether they graduated this millennium or the last. A

Late-Life Adventure: My

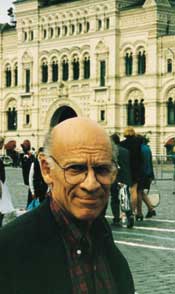

Two Years in the Peace Corps IT WAS PAST MIDNIGHT AND I COULDN'T SLEEP. A COLD WIND RAPPED AT THE LEAKY WINDOWS, AND WHAT LITTLE HEAT THERE HAD BEEN IN THE SMALL FOURTH-FLOOR APARTMENT OF MY SCHOOL HAD LONG SINCE DEPARTED. The building was like a fortress, almost 100 years old, now empty and locked for the night. In a few hours a torrent of 650 adolescents would be roaring through the halls below. I was feeling restless and edgy. It had been my worst day. Going through my mind was what to do about the noisy and disruptive behavior in one of my classes. I was still having trouble keeping this class quiet during lessons, and my patience was weakening. I hadn't yet figured out what I was doing wrong. I was thinking of going to the director, but what would I tell him? After six weeks I was having doubts about teaching for two years in this foreign land 3,000 miles from home. From under my covers I stared into the darkness and wondered what I had gotten myself into. If any of my family or friends thought I was a bit reckless or naive when I told them I was going to join the Peace Corps, they kept it to themselves. I'm sure they wondered why a 67-year-old grandfather would want to leave the comforts of home to live in a remote village in some far corner of the world. By the time I retired in July 1996 I had already applied to the Peace Corps to teach English and requested to be sent to South America because I wanted to learn Spanish. Within the next several months I had a massive tag sale, put my furniture in storage, sold the house I had lived in for 36 years, and waited. I received my "invitation" in April 1997. I was wondering which country it would be: Ecuador, Peru, perhaps Bolivia. Then I read the letter. I was going to Poland, with departure in two months. The pang of disappointment was brief, however, because I had lived in Munich for two years in the mid-1950s but had not traveled in Central Europe. In early June our group of about 80 volunteers assembled for "staging" in Washington, D.C. After several orientation sessions and an overnight, we flew to Warsaw and took a bus to Radom, an industrial city of 250,000 located two hours to the south, where we would spend the next 11 weeks receiving our pre-service training. In addition to excellent instruction in Polish, there were classes and speakers on cross-cultural issues. Fifty of us had courses in teaching English as a foreign language. The other 30 would be serving as consultants to environmental agencies. Each of us lived with a local family (who received a stipend from the Peace Corps), so from the beginning we were exposed to Polish food, customs, and the language. My "family" was a friendly, 40-something factory worker whose wife lived in a village 20 miles away, where she taught in an elementary school. He spoke no English, but in spite of that, we got along well. Most of the host families lived in apartment complexes scattered throughout the city. Children or parents often gave up their rooms and slept on the living room couch to accommodate their American guests. I was fortunate to have more privacy than many of my friends and was spared being witness to family squabbles and pressure from "host moms" to eat more than some thought humanly possible. In late August I arrived in Swidnica, a city of 65,000 in southwest Poland near the Czech border. The school director greeted me with a warm handshake and a bouquet of flowers, as is the custom. Dzien dobry. Witamy w naszej szkole.(Hello. Welcome to our school.) I had only three days to get settled and prepare for classes, where I would soon discover that my preparation had little to do with the realities of what went on in the classroom. During the Communist era, Russian was the main foreign language taught in the schools. The Peace Corps came to Poland in 1990 at the request of the Ministry of Education with the goal of having a new generation learn English. The agreement was for volunteers to teach in high schools (lyceums) for about ten years, thus the Peace Corps will leavePoland in June of 2001. To be assigned an American teacher, a school had to provide housing, either at the school or in the community. My modest apartment was fairly comfortable, though to save coal in the winter the director didn't heat the school on weekends; my portable gas heaters usually provided adequate heat in my apartment. During especially cold weather my students sometimes had to wear jackets and mittens in class, where the temperature wasn't much above 50 degrees. The Peace Corps required a school to have a Polish teacher of English grammar; the volunteer focused mainly on conversation. To my surprise I was informed that I would be the only teacher for 120 third-year students, teaching mostly grammar. For me, a retired psychotherapist who hadn't been in a classroom for decades, the task initially felt overwhelming. I SAW MY STUDENTS IN CLASSES OF 30, TWO OR THREE TIMES A WEEK. I came to enjoy teaching, but dealing with classroom discipline was another matter. The morning after my restless night, the students in my problem class could tell something was amiss by the look on my face. "I have something to tell you. I have decided to go to the director today and tell him that I don't want to be your teacher this year. This class is too noisy and disruptive. There is too much talking during lessons. Some of you have been rude. I've reminded you enough." There was a long pause. Then Katarzyna stood up. Holding onto her desk she said, "Please, Mr. Siddall, don't go to the director. We will try harder to be quiet. Please give us another chance." Then there followed pleas from Pawel, who the day before had lent me a cassette of his favorite music; Lukasz, the best student in class; and Magda, one of the worst offenders, but always cheerful. Things were better after that, and it was some consolation to learn that they were often this way with their Polish teachers. This was perhaps the brightest class in the school (almost half were A students), and keeping them busy and interested was a major challenge. I learned a lot from them about Polish history and culture, of which they were proud. Once I asked what I should know about their social customs, and Dorota informed me that it's impolite for a man to talk to a woman with his hands in his pockets. As I look back, most of my students were respectful, hardworking, and often fun to be with. Many did very well academically and went on to the university. In my second year I shared teaching with the three other English teachers who taught mostly grammar. I had 210 second- and third-year students. Instead of 30 in each class session, I had 15, which made teaching much easier. We spent more time on writing and talking about a variety of subjects, such as the environment, the culture of the United States ("Mr. Siddall, were you a hippie?"), favorite films and movie stars, pop music, geography, the NATO bombing in Kosovo, art history, listening to selections from Handel's Messiah at Christmas, writing a brief autobiography, and sports. "Have you seen Michael Jordan play basketball?" Tomek, whose mother lived in Canada, asked one day. "No," I said, "but in America I live only 30 kilometers from Springfield, Massachusetts, where basketball was invented and where the Basketball Hall of Fame is." Tomek and his friends seemed delighted with this bit of information. It was his life dream to see the Chicago Bulls play. We also had fun singing in English, although girls enjoyed this more than the boys. Their favorite was Oh! Susanna. My school, with an enrollment of 650, was considered the best lyceum in the city. Students were required to take an entrance examination. Academic standards were high and a lot of homework was assigned, which allowed students little free time. Unlike schools in our country, there are very few extra-curricular activities and no interschool sports programs. Students are required to learn two foreign languages. Almost all the students in my school chose English, which many had been learning for several years. Other languages available were German, Russian, French, and Latin. Except for the teachers of English, none of the other 23 instructors spoke much English, so for the first several weeks I was pretty much ignored in the teachers' room. I felt isolated and wished my Polish were better. Then one morning a woman I had not met came up and said, "Good morning. My name is Urszula and I teach English here part time. How do you like it here in our school?" I thought to myself, Not all that well so far. We chatted for a few minutes before the bell rang, and then she said, "I would like to invite you to my home for supper sometime soon and meet my husband and two sons." This was my first invitation, and over time I would become good friends with Urszula and her family. Her husband Alexander was an engineer who worked for the municipal water department, and their two pre-adolescent boys were quite good in English but a little shy. During many of my visits there were relatives, friends, or neighbors sitting around talking and laughing. I sometimes went with the family on excursions in their VW Golf over winding roads through the rolling countryside, with the mountains bordering the Czech Republic in the distance. I taught the minimum requirement of 18 hours a week from Monday through Thursday, but many hours were necessary for classroom preparation. I met with students after classes, too, for practice in conversation. I was paid a beginning Polish teacher's salary of a little more than $200 a month by the school, and $90 was added by the Peace Corps. While this was adequate, especially because I didn't have to pay rent, many teachers in Poland struggle to make ends meet, even if they teach extra hours. The average monthly wage nationally is about $400. An extra project included meeting with a group of English teachers from other schools in the city, and another involved the local Lutheran church, known as the Peace Church because of its association with the Peace of Westphalia that ended the Thirty Years' War in 1648. It was built in 1656 and is unique for its wooden construction, architectural design, and beautiful interior artwork. Though the church could seat 3,000 people, only about 50 attend Sunday services. Audiocassettes in Polish, German, and English were available, but when I heard the one in English I could hardly understand it. With encouragement from the pastor, I did some research, wrote a new text, then recorded it in a professional studio. DURING MY FIRST YEAR IN SWIDNICA (PRONOUNCED SHVIDNEETZA), I was the only American or native speaker of English. (The following year a woman from England came to teach in another school.) One of the local weekly newspapers published an article about me, and because of this I made another good friend. Wioletta was an obstetrician whose parents and sister lived in Chicago. She contacted me after reading the article to ask if I would help her improve her English. Though she had an active private practice in addition to her staff duties at the hospital, she was considering emigrating to join her family in the States. Also, she was earning much less than physicians in Western Europe or the United States. Our lessons were informal, often over coffee, or sometimes having supper at her home with her partner, Jurek, who worked as a pharmacist, and she invited me to special occasions such as Christmas Eve dinner with other guests. When she had time we also did some sightseeing, driving around in a white 1980s Dodge, an ex-police car that Jurek had shipped over from California for reasons that I never quite understood. The Poles like to eat, drink, and socialize, so being invited into their homes was always fun. Though Poland isn't famous for its cuisine, there are a variety of interesting dishes as a result of so many cultural influences over the centuries. Meals on Christmas and Easter are the most elaborate, and, of course, most celebrations would not be complete without plenty of beer and vodka. To fully appreciate these occasions I made a real effort to learn Polish. I found it a difficult language, and though I would eventually become moderately proficient, it would be a source of frustration during my two years not to become more fluent. My students enjoyed testing my pronunciation skills with such words as przyrodoznawstwo (natural science), czterdziestoletni (40 years old), dalekowzrocznosc (far-sightedness), and skrzypce (violin), usually to much laughter, but they cheered when I got it right. My tutor and friend during my last year was Anita, a newspaper editor who spoke excellent English. We met weekly at the small apartment she shared with her Artur, who was also in the newspaper business. Anita was widely read, easy to talk to, and always patient as I struggled with Polish grammar. I especially enjoyed her helping me write accounts in Polish about my trips. I traveled extensively during my tour, both within Poland and in other countries. The high points for me, besides sampling the food, were wandering through the art museums and going to symphony concerts in Warsaw, Krakow, Venice, Florence, Milan, Vienna, Munich, Dresden, Berlin, and, with a touch of the exotic, Moscow and St. Petersburg. I usually went by train, but flew to Russia because of the distance. Many Polish cities have excellent opera and theater companies, art museums, and a variety of on-going cultural events such as jazz and film festivals. In retrospect, the most difficult time for me was the first three months, partly because of the adjustment to the demands of teaching, but also because my Peace Corps friends were miles away and I was just beginning to make Polish friends. Fortunately, I had brought a laptop computer and portable printer, so I could maintain correspondence with family and friends. I left Poland at the end of June 1999. After stopovers in Amsterdam and Cardiff, Wales, followed by three delightful weeks in Ireland, I arrived home on July 24. Since then I have bought a house, retrieved my furniture, and have begun studying Spanish. Maybe I'll get to South America after all. Lawrence Siddall was born in China, where his father was a medical missionary, and grew up in Oberlin. After graduating from Oberlin College, he served two years in the U.S. Army, the final year in Munich. Following his military separation there he attended lectures in art history for two semesters at the University of Munich. In September 1956 he began what he calls his first big adventure by driving overland with an army friend from Germany to India in a VW Beetle. From there he worked his way back to the States on a freighter. He earned a MSW degree at the University of Connecticut, an EdD degree at the University of Massachusetts, and, from 1962 until his retirement in 1996, was a psychotherapist, most recently with Kaiser Permanente in Amherst, Massachusetts, where he now lives. Siddall says that he is learning Spanish, and volunteering several hours a week at a local elementary school, helping children for whom English is a second language. He has been working with two boys and a girl in third grade from Tibet, Russia, and Mongolia, and a boy in fifth grade who is from Japan. "Being with them in their classrooms is a mini-adventure in itself," he observed. |