|

Issue Contents :: Bookshelf :: Page [ 1 2 ]

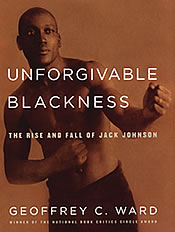

Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson

By Geoffrey C. Ward '62

Alfred A. Knopf , 2004

Reviewed by Tim Tibbitts

The white world was not ready for a black heavyweight boxing champion in 1908, but it was not in Jack Johnson’s nature to wait for white people—or any people—to give their assent. In fact, in and out of the ring, Johnson rejected limitations of all kinds, from where he could live to whom he could love to how fast he could drive. And he paid mightily for his choice. The reaction of most whites to Johnson’s victory over Canadian Tommy Burns on Boxing Day 1908 was despicable. To make matters worse, for all his charm and ability to laugh off the most hideous racial slurs and gestures, Johnson’s conduct outside the ring only added fuel to the fire of white hatred. Thus, to read Unforgivable Blackness is to read both a triumphant sports story and a tragic human one. The white world was not ready for a black heavyweight boxing champion in 1908, but it was not in Jack Johnson’s nature to wait for white people—or any people—to give their assent. In fact, in and out of the ring, Johnson rejected limitations of all kinds, from where he could live to whom he could love to how fast he could drive. And he paid mightily for his choice. The reaction of most whites to Johnson’s victory over Canadian Tommy Burns on Boxing Day 1908 was despicable. To make matters worse, for all his charm and ability to laugh off the most hideous racial slurs and gestures, Johnson’s conduct outside the ring only added fuel to the fire of white hatred. Thus, to read Unforgivable Blackness is to read both a triumphant sports story and a tragic human one.

Born to ex-slaves in 1878, Johnson was 21 when he first attracted attention with the use of his fists by winning a Battle Royale, a disturbing charade in which blind-folded black men punched each other until only one was left standing. Less than a decade later, he had boxed his way through many of the best fighters of his day, emerging as a legitimate challenger to Tommy Burns. But before Johnson could win that match, he had to fight for the right to fight. Burns, unlike his predecessor Jim Jeffries, who simply refused to fight a black man for the title, took a more indirect tactic: naming an exorbitant purse of $30,000 before he would fight. Finally, in 1908, pressure from sportswriters and a savvy promoter’s willingness to put up the money forced Burns to face Johnson. Johnson dominated the match and became the undisputed heavyweight champ of the world.

Every champ becomes a target for challengers. But in Johnson’s case, ousting the black champ became a racial crusade, and the search for a “white hope”—the boxer who could restore the title to the white race—was conducted with unparalleled ferocity. Outside the ring, Johnson’s championship was greeted no less intensely. Whites by and large resented him, and his penchant for white women led not only to derision and death threats, but ultimately to a six-year exile and a one-year prison term.

Ward, the well-known co-author with Ken Burns of such documentaries as Jazz and The Civil War, is exhaustive in his research. When the available sources are inconclusive, he simply presents all sides, unafraid to leave loose ends unresolved. Perhaps there is no better example of Ward’s respect for his readers’ ability to think for themselves than the way he deals with the racist language that permeates the newspapers of the day. Ward presents the newspaper accounts unadorned by editorializing on his part, allowing the accumulation of racial slurs to horrify all by itself.

Unforgivable Blackness tells a riveting sports story, but the audience for this book extends well beyond sports fans. Anyone interested in the social history and racial tribulations of the United States—even those appalled by the brutality of boxing itself—will find much of substance in this thoughtful biography.

Tim Tibbitts is a freelance writer in the Cleveland area.

Next Page >>

|