|

Issue Contents :: Feature :: Project Winter Term :: [ 1 2 3 4 ]

Project Winter Term

Oberlin students are nothing if not adventurous. Each January, they dive without qualm into life’s muddy middle, be it in Santo Domingo, Beijing, or Antarctica. Whether it’s to explore a career path, reconnect with an ethnic heritage, or satisfy a yearning for deeper knowledge, winter term finds Obies in far-flung places throughout the globe. Inspiration for projects comes from a variety of sources. Group ventures, when sponsored by professors and bundled with classroom work, often take on the feel of real-world lab experiments. Internships offered by alumni expose students to career paths they may never have before considered. Even

students who spend winter term on campus immerse themselves in their their projects, be it by writing original operas or reenacting the stories of Nazi concentration camp survivors.

Expenses for treks to distant shores can be defrayed by grants from academic departments, the Winter Term Committee, or Oberlin-affiliated organizations such as Shansi; alumni also help by providing housing and meals. “The hallmark of winter term is flexibility and the seemingly endless possibilities it offers,” says Brian Alegant, professor of music theory and chair of the Winter Term Committee. “Students can explore new fields and learn new skills, like playing an instrument, writing a concerto, doing collaborative research with faculty members, training for a marathon, or interning with alumni. In short, winter term can be anything and everything you want it to be.” —Betty Gabrielli

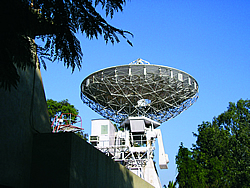

Raman Research Institute in Bangalore, India Raman Research Institute in Bangalore, India

Ben Sulman, junior physics major

Studying and living at a physics research institute was an amazing experience. Every day I was surrounded by the best researchers in the field.

The Raman Research Institute is funded by the Indian government. There, grad students, post-docs, and professors study astrophysics, astronomy, liquid crystals, quantum gravity, and optics. My research involved writing software used to search for pulsars. The chance to do real research, even for a short time, is extremely valuable to any physics student. Working with people of the caliber found at RRI is a rare opportunity. One of the visiting professors during my stay was Claude Nicollier, a Swiss astronaut who flew three Space Shuttle missions and repaired the Hubble Space Telescope. I drank tea and chatted with him.

That this research took place in India added immensely to the experience. Phil Korngut (another Oberlin physics student) and I explored Bangalore, the so-called Silicon Valley of India, and visited several incredible temples, gardens, and other tourist spots. We participated in the global physics community and established ties that reach across national boundaries.

Above: The radio telescope at Raman Research Institute.

Internship with Massachusetts Senator Fred Berry

Rachel Welsh, first-year, intended politics

or environmental studies major

A few weeks into my internship at the Massachusetts State House, I was asked to attend a forum on opiate use in the North Shore area. I spoke with police officers, parole officers, politicians ranging from mayors to other senators, and parents of children who had died from heroin and other opiate overdoses.

Afterwards, Senator Berry’s legislative aids asked me to research the opiate epidemic and write a summary of the most striking facts regarding its use in Essex County. I then met with the senator to discuss my findings and brainstorm drug education programs that might be funded.

Through this inside view I have come to realize how interesting—yet also challenging—a job in politics would be. I would need to make compromises on my ideals to satisfy my constituents. I would not be able to fight for every noble cause. I could, however, effectively change the problems in my area. That power is very appealing to me.

Socioeconomic study in Beijing, China Socioeconomic study in Beijing, China

Lily Schatz, junior East Asian studies major

How has the emerging capitalist system in China changed the lives of the people of Beijing? To paint a picture of life in Beijing today, sophomore Roma Eisenstark and I interviewed residents of all walks of life: college students, hutong residents, the elderly, outside laborers, political party members, and members of the emerging nouveau riche.

Our questions were wide ranging. We asked about everyday family life: How has the process of obtaining and preparing food changed? How far from your grandparents did you live as a child? How far away do your grandchildren live from you?

We sought information about how the nature of social services has changed since the Communists came to power in 1949: How did you obtain medical care under the Communists (e.g., “barefoot doctors”)? How do you obtain medical care today? In both circumstances, how was this care paid for? How has the role of the danwei, or work unit, changed over the course of your career? How do you experience the role of the danwei in your life today? We also asked questions on political issues: What are your views on sweatshops and party corruption?

I never imagined we would receive as warm a reception as we did. Person after person expressed interest in our project and even gratitude, telling us how much such a project needed to be done. “Rebecca,” a high school freshman who assisted us with translating, wrote to us: “I really admire your work. Even our Chinese are afraid to interview others. You have got some classical examples of Beijing. I can also learn a lot from them.”

Of course there were also people reluctant to open up to us or who didn’t understand why we wanted to undertake such a project—most notably a party member at Beijing University—but they were the minority.

Above, from left: “Penny,” Lily Schatz ’06, and Roma Eisenstark ’07

Next Page >>

|