A Golden Age for Oberlin

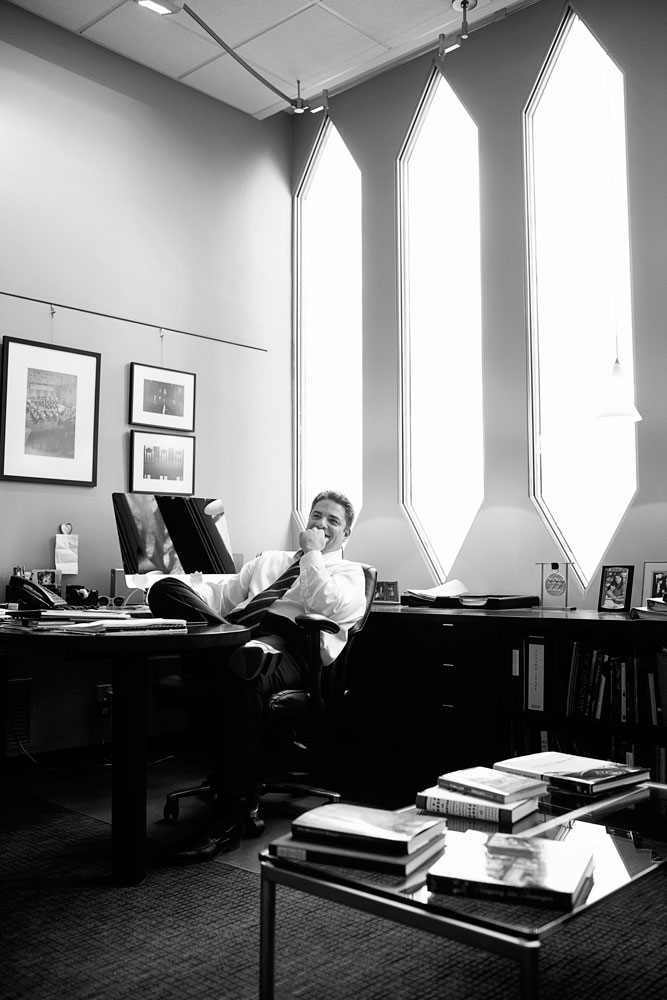

Dean David H. Stull's tenure has been marked by great achievements—and great love for his alma mater

by Erich Burnett

Photographs by Tanya Rosen-Jones '97

David Stull's most enduring memory at the helm of the Oberlin Conservatory actually started with a twinge of terror.

On sabbatical during the fall of 2009, the recreational pilot had just lifted his Cessna Skylane above the northeast Ohio landscape, en route to a visit with schoolchildren half a country away. Prior to takeoff, Stull’s longtime assistant back in Oberlin assured him that she wouldn’t call unless there was a grave emergency.

Then a few minutes later, she did exactly that.

“I need to talk to you,” his assistant, Greta Williams, said nervously. Stull returned the plane to earth and dialed her back.

“I said, ‘What’s up?’ And she said, ‘Well, the White House called...’”

For the next four months, Dean Stull was sworn to secrecy: Oberlin had been awarded the National Medal of Arts— an almost unheard-of gesture for an institution of any kind, and a resounding note of validation for Stull’s achievements in his first five years on the job.

“This will rank as one of the golden ages of the conservatory,” says Steven Plank, a professor of musicology. “David is visionary in a way that asks how a conservatory of the 21st century needs to be different from one of the 20th century. He’s a great steward of what this conservatory has been, but he also prompts us to think imaginatively about what it can be.”

Beginning in July, Stull will assume the role of president at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, taking with him more than 17 years of Oberlin experience as both student and administrator. He has said repeatedly that Oberlin will always be his home, and the conservatory family he leaves behind will be forever grateful for the academic home he established here. To Stull, they were the lifeblood of a world-class institution; and to them, he was the gregarious leader who ensured that every voice would be heard.

New Levels of Greatness

Perhaps the finest compliment that can be made of David Stull’s tenure is this: Talk about his legacy with any number of faculty and friends of the conservatory, and you’ll get a recitation of defining moments that runs longer than a Mahler symphony. He excelled at elevating Oberlin’s international status, at securing gifts and funding for a wide range of ini- tiatives, at giving life to his faculty’s dreams, and at ensuring that the conservatory’s students earned opportunities to play on the world’s finest stages.

“David Stull’s vision, drive, and acumen have elevated the conservatory’s already lofty reputation to new heights,” says Oberlin College President Marvin Krislov. And Stull wasted no time in getting started.

When the conservatory found itself in need of a new dean early in 2004, it also found little reason to look beyond the office of its associate dean at the time: 1989 graduate David Stull. In four years on the job, he had earned such admiration that those who were charged with finding the next head of the conservatory were certain their leader was already among them.

When the conservatory found itself in need of a new dean early in 2004, it also found little reason to look beyond the office of its associate dean at the time: 1989 graduate David Stull. In four years on the job, he had earned such admiration that those who were charged with finding the next head of the conservatory were certain their leader was already among them.

“The most telling thing was not that they promoted David from within, but that there was no search,” says Plank, who has been teaching at Oberlin since before Stull’s days as a tuba-playing student. “There was thinking among the faculty that we could do a search, but why bother?”

"David Stull's vision, drive, and acumen have elevated the conservatory's already lofty reputation to new heights."

Oberlin President Marvin Krislov

To the surprise of no one, the new dean hit the ground at a full sprint.

“Working with the faculty to recognize how wonderful we are was job one,” Stull remembers. “One of the initial conversations we had was how we planned to present our program to the world and whether we were truly willing to own the things that are the strengths we have: the fact we’re attached to a robust liberal arts college, that we serve undergraduates, and that we’re in the middle of the lovely wilds of northern Ohio.” This, to Stull, represented Oberlin’s opportunity to present the conservatory as the way to teach music education, as opposed to it merely being one way.

Just as quickly as Stull set about solidifying the conservatory’s identity, he turned his attention to its renowned jazz program and the decrepit gymnasium it had called home for years. “We needed to bring jazz into the center of the conservatory,” he recalls thinking. “There really wasn’t another project we could imagine until we dealt with that.”

What resulted was the most visible achievement of his tenure: the $24 million Bertram and Judith Kohl Building, an architecturally stunning,state-of-the-art facility that united the conservatory’s key pillars at the center of campus. A project years in the making, it was dedicated in 2010 to great fanfare, including visits from Stevie Wonder and Bill Cosby.

“He’s a big thinker, and he brought a big vision for how you could take an institution that is already recognized as being one of the best in the world at what it does, and still have incredible ideas for how to take it forward,” says Oberlin Trustee Stewart Kohl ’77, CEO of a private equity firm who, with his wife, Donna, was the key contributor who made the Kohl Building possible.

“He’s a big thinker, and he brought a big vision for how you could take an institution that is already recognized as being one of the best in the world at what it does, and still have incredible ideas for how to take it forward,” says Oberlin Trustee Stewart Kohl ’77, CEO of a private equity firm who, with his wife, Donna, was the key contributor who made the Kohl Building possible.

Among Stull’s innumerable other contributions: He led student tours across the country and to China, exalt- ing the Oberlin Orchestra as well as the conservatory’s other world-class ensembles. He established a commercial record label, Oberlin Music, to showcase the work of students and faculty. He developed key relationships and funding sources that have resulted not only in new construction and sweep- ing renovations on campus, but also in new programs, new professorships, and new collections dedicated to enhancing the learning experience.

Through Stull’s great effort, the conservatory ushered in the Rubin Institute for Music Criticism, the annual Thomas and Evon Cooper International Competition, and the wildly successful Creativity & Leadership Project, which encourages Oberlin students to tap into their entrepreneurial instincts.

“David’s energy and his enthusiasm are contagious,” says Thomas Cooper ’78, a partner for an international finance group and an Oberlin trustee. Cooper and his wife, Evon, felt that same enthusiasm five years ago when Stull approached them with an opportunity to sponsor a piano and violin competition for teens. In addition to a grand prize of $10,000, finalists would perform with the renowned Cleveland Orchestra.

“If we could get that going, it would be unique,” Stull told Cooper.

“I said, ‘Unique, huh?’” And with that, the Cooper Competition was born.

An Advocate for Everyone

If you walked down the hallway and asked any faculty member what our vision is, you would always get some version of ‘excellence.’ And that all comes back to David,” says Associate Dean Andrea Kalyn, who will serve as interim dean during the search for Stull’s successor.

From his first days in the dean’s chair, Stull earned the respect and admiration of faculty through his great passion for their endeavors and his attentive ear to their concerns. It’s a theme that has carried through to his final days on campus.

From his first days in the dean’s chair, Stull earned the respect and admiration of faculty through his great passion for their endeavors and his attentive ear to their concerns. It’s a theme that has carried through to his final days on campus.

“David has been an amazing leader for the conservatory in every way that a leader should lead,” says Professor Timothy Weiss, director of conducting and ensembles. “He’s raised the profile of the school—not only made us better, but told the world we are the best. That translates to better recruiting, better students, a better program, and ultimately a better school.

“But he’s also given the faculty a sense of direction, to where we all feel we’re working with a purpose. He’s had an open door, so that everyone in the building feels comfortable walking in and talking about their ideas, concerns, and projects they want to initiate. He’s not only been a good listener, but he’s a great advocate for every program.”

"Great administrators are those who advocate not for their own interests, but equally for all interests.

And that's what David has done."

Professor Timothy Weiss

Nowhere was that more evident than in the Conservatory’s January 2013 Illumination Tour of New york City, which featured performances by the Oberlin Orchestra, the Contemporary Music Ensemble, Oberlin Baroque, the Oberlin College Choir, the Faculty Jazz Ensemble, and an all-star lineup of alumni.

“Great administrators are those who advocate not for their own interests, but equally for all interests,” Weiss says. “And that’s what David has done.”

A Legacy of Inspiration

For four excruciatingly giddy months, David Stull knew his conservatory had won the National Medal of Arts, yet he was forbidden to mention it until President Obama went public with the news.

Finally, on February 24, 2010, that day had come. Scheduled for an afternoon flight to Washington to accept the award, Stull insisted his faculty and staff not be blindsided by the news secondhand.

And so he convened an emergency meeting to be held in Warner Concert Hall.

“Everyone was panicked,” Stull recalls with a satisfied smile. “We had never had an emergency meeting—in fact, we usually end up canceling most of our faculty meetings.”

Fears of the unknown mixed with an uneasy sense of certainty: Either drastic budget cuts were looming, or Stull was leaving. “They were taking bets!” he says.

As the dean launched into a round of It’s been a pleasure to serve you filibustering, an acoustical baffle behind him began its labored descent to the stage floor. Minutes later, as tensions rose to a crescendo and the panel finally disappeared, a table came into view—covered with glasses of champagne.

Bursts of laughter gave way to joyful tears, and then to a round of applause.

Three years later, the unthinkable has come to pass: David Stull is leaving, but not without first helping the world to see the great heights Oberlin can achieve.

“It’s hard to imagine the place without him,” says Plank. “The fact we can do that speaks to the way that he’s nurtured this place. He’s made it a very dynamic place, and because of that we are prepared to move ahead. He’s given us the model to inspire the effort.”