The Selch Connection

A major collection of instruments and artifacts bolsters the study of American music history

by Jessica Downs '10

Photographs by Dale Preston '83

Frederick and Patricia Bakwin Selch devoted a lifetime to creating one of the world’s most comprehensive collections chronicling American music history. Now, a decade after the death of her husband, Patricia Selch has ensured that their treasures will illuminate that rich history for future generations at Oberlin and beyond.

Frederick and Patricia Bakwin Selch devoted a lifetime to creating one of the world’s most comprehensive collections chronicling American music history. Now, a decade after the death of her husband, Patricia Selch has ensured that their treasures will illuminate that rich history for future generations at Oberlin and beyond.

In September 2012, the Oberlin Conservatory unveiled the Frederick R. Selch Classroom, a technologically superior learning space that represents the final component of an expansive gift made by the Selches—a gift that underscores Oberlin’s position as a key center for the study of American music.

Gifted in 2008, the Selch Collection includes some 800 instruments, 9,000 rare books, and a large collection of artworks depicting musical themes. Patricia Selch is also the benefactor of the new Frederick R. Selch Professorship of Musicology, a critical component in the expansion of music studies at Oberlin.

“I’m so happy that the collection will be made available in these ways,” says Selch. “People have traditionally gone to places like Oxford to study American music history. Why go there when they can come here?"

Last fall, the conservatory hosted public and private events in celebration of the Selches’ gift. Five exhibits showcasing key components of the collection were featured across campus throughout the fall semester.

“We are enormously grateful to the entire Selch family for their extraordinary generosity to Oberlin,” says David H. Stull ’89, the conservatory dean who orchestrated the donation. “[Frederick] and Pat Selch’s vision for a center for the study of American music history will finally be brought to fruition, and their support will immeasurably advance the study and performance of music at the highest level.”

|

|

|

|

A Stunning Learning Space

An accomplished publisher and creator of early television commercials, Frederick Selch—known to friends and family as Eric—also nurtured a profound passion for music throughout his life. Along with his wife, he reveled in the thrill of the hunt for unique and often forgotten instruments and seminal books. He earned a PhD in American studies from New York University, helped found the American Musical Instrument Society, and created an ensemble of professional and amateur players known as the Federal Music Society. Through it all, he demonstrated a remarkable desire to share his collection, his knowledge, and his enthusiasm with others. Today, that passion is evident in the Selches’ wide-ranging contributions to the learning environment at Oberlin.

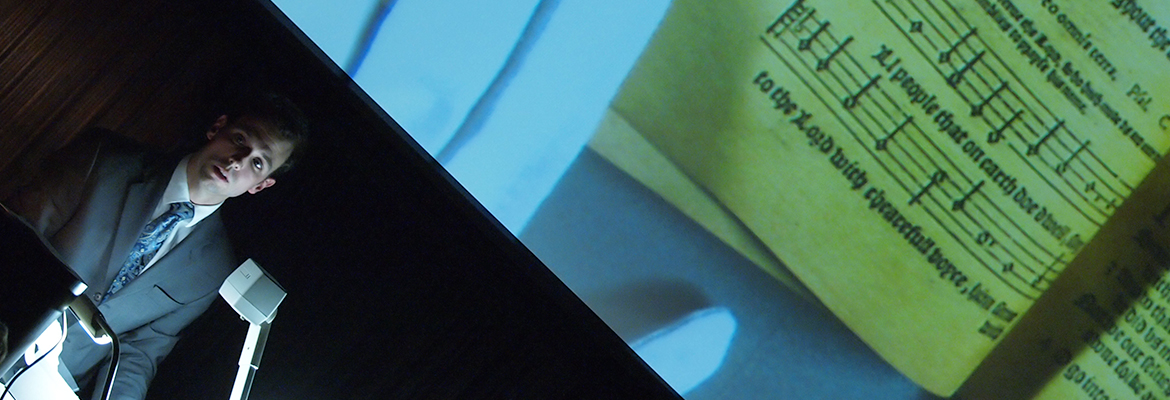

The Selch Classroom, on the newly renovated second floor of Bibbins Hall, is a technology-enhanced “smart” classroom that allows networking, audio-visual, and audience-response capabilities. It features towering walnut cabinets, which house a portion of the Selch Collection, and wide- plank walnut flooring; custom lighting illuminates the room’s UV-filtered glass cabinet fronts. More than just a beautiful addition to campus, it’s a highly functional one too.

The Selch Classroom, on the newly renovated second floor of Bibbins Hall, is a technology-enhanced “smart” classroom that allows networking, audio-visual, and audience-response capabilities. It features towering walnut cabinets, which house a portion of the Selch Collection, and wide- plank walnut flooring; custom lighting illuminates the room’s UV-filtered glass cabinet fronts. More than just a beautiful addition to campus, it’s a highly functional one too.

“The new Selch Classroom provides dedicated space for dialogue between students, and between students and teachers,” says Professor Steven Plank, chair of Oberlin’s Department of Musicology.

“At the same time, it nurtures ongoing dialogue with the artifacts housed there.”

The five initial exhibits featured on campus spanned the 16th through 19th centuries. Created by Selch Curator Barbara Lambert, they included instruments—both strange and familiar—and artifacts that provide a fascinating glimpse into the scientific and cultural practices of early America.

Installed in the Selch Classroom, the exhibit Beginnings of American Music and Musical Instruments contained a timeline of musical evolution experienced by early American colonists.

Installed in the Selch Classroom, the exhibit Beginnings of American Music and Musical Instruments contained a timeline of musical evolution experienced by early American colonists.

Chronicling a period highly influenced by the Protestant church, it depicted the progression from simple psalms and tones played on pitch pipes to more poetic song-style hymns that were complemented by string and melody instruments.

The exhibit’s theme was derived from Selch’s doctoral work at NYU. The objects “captured Eric’s imagination,” says Lambert, pointing out the basic but elegantly carved wooden pitch pipes displayed alongside a 1690s psalm book that is startlingly well preserved.

The other four fall-semester exhibits revealed their own fascinating stories.

The Musical World of Actress and Abolitionist Fanny Kemble described in portraiture, playbills, and manuscripts the life of a remarkable woman. Born in Britain into a dynasty of major actors, Kemble married American Pierce Butler, heir to cotton, tobacco, and rice plantations worked by hundreds of slaves. Despite Kemble’s enormous popularity as an actress, her true calling was as a writer; her personal journal, which includes firsthand accounts of the slave industry, had a profound influence on British attitudes toward slavery.

The exhibition Frederick R. Selch, in the conservatory library, introduced viewers to the collector himself. Among the items on view were photos of Eric and Patricia Selch in their New York City brownstone, along with books hand-bound by the couple.

A clarinet by the important early 19th-century maker William Whiteley, a baroque- style violin made and played by Tarahumara natives from Mexico, and a “tenor violin” represent significant areas of scholarly work by Selch and important parts of his collection.

The exhibition Frederick R. Selch, in the conservatory library, introduced viewers to the collector himself. Among the items on view were photos of Eric and Patricia Selch in their New York City brownstone, along with books hand-bound by the couple.

A clarinet by the important early 19th-century maker William Whiteley, a baroque- style violin made and played by Tarahumara natives from Mexico, and a “tenor violin” represent significant areas of scholarly work by Selch and important parts of his collection.

The science of music was showcased in the Science Center exhibition Musical Instruments and the Harmonic Series. In collaboration with physics professors Bruce Richards and Chris Martin, the exhibit complemented a course on acoustics.

The Selch Collection’s central home at Oberlin is found on a workshop-type floor in the belly of the Bertram and Judith Kohl Building. There, a jingling johnny, cittern, bumbass, and a bass viol shaped like a pumpkin rest among hundreds of other instruments, including those of Native and Central American peoples. Steel engravings, woodcuts, oil paintings, playbills, and programs are among other artifacts and ephemera too numerable to list.

Floor-to-ceiling glass display cases at the entrance of the workshop housed the exhibit 19th-Century European and American Music. It was created as a final exam by students in a new course called Hands-On Music History, taught by Lambert and Professor of Musicology Claudia Macdonald. In spring 2013 alone, three classes on campus directly incorporated the Selch Collection into their curriculum.

“Eric was not just a collector,” Patricia Selch said in a 2008 interview with critic Heidi Waleson. “He was very much a scholar, and he built his collection to be used.”

Inheriting the Vision

James O’Leary, Oberlin’s newly appointed Frederick R. Selch Assistant Professor of Musicology, boasts an enthusiasm that matches his knowledge of American music history. He likens the collection to “an anthropology of music.” His course, and the way that he guides students’ interaction with the collection, offers extraordinarily deep insight into how music in America not only was performed, but how it was bought and sold, and depicted in art and in other cultural iconography, such as cartoons and music trading cards.

James O’Leary, Oberlin’s newly appointed Frederick R. Selch Assistant Professor of Musicology, boasts an enthusiasm that matches his knowledge of American music history. He likens the collection to “an anthropology of music.” His course, and the way that he guides students’ interaction with the collection, offers extraordinarily deep insight into how music in America not only was performed, but how it was bought and sold, and depicted in art and in other cultural iconography, such as cartoons and music trading cards.

O’Leary encourages study not only of the what of music, but also the ways in which people interacted with it and the influences it had on their actions and beliefs. And he marvels at the possibilities for the collection that will continue to emerge over the years.

O’Leary encourages study not only of the what of music, but also the ways in which people interacted with it and the influences it had on their actions and beliefs. And he marvels at the possibilities for the collection that will continue to emerge over the years.

“The potential for using the collection is somewhat unknown at this point,” he says. “It’s a gift that keeps on giving.”

Jessica Downs is former Assistant Director of Conservatory Communications. A Juilliard-trained oboist, she earned her master of music in teaching at Oberlin College in 2010.