SATURDAY

Seth and Courtney got married in a floral shop in midtown. Empty chairs reminded us of all those from out of town who couldn't attend. So that Seth's family in Chicago could participate, the best man broadcast the ceremony to them via his cell phone.

The wedding guests gave toasts, and there was much talk of the week and how people were glad that Seth and Courtney decided to go ahead with their plans. When Courtney finally spoke, she said, "There were moments on Tuesday when I didn't know where Seth was, or how he was, or if he was. So when it came time to make the decision, yes, I was getting married. Yes."

Seth and Courtney's friends are a colorful group, including bartenders, bouncers, strippers, comic-book artists, martial artists, and playwrights. One woman who tended bar four blocks from the World Trade Center said that she could never go back to her job. She didn't know the names of most of the men who frequented her bar, but she knew their faces and what they drank. If she went back, she'd be constantly reminded of who was no longer there.

One man told me that for days he was too numb to feel personally affected by what had happened. Then a friend mentioned the man's tattoo. He showed me what years earlier had been inked permanently onto his forearm. It was a New York skyline, complete with the twin towers.

After

the wedding, Amy and I walked to Union Square, filled with people, candles,

and memorials. Chalked onto various monuments were slogans like ANGER, NOT

HATE and PEACE. An older white woman and a black man wearing a flag bandanna

performed a flute duet of "Glory, Glory Hallelujah." Tibetan monks walked

through the crowds. A group sang Christian prayers. At the south end of

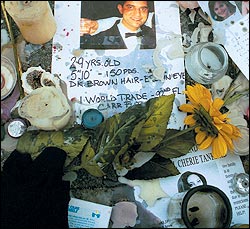

the square, in the largest memorial, stood a peace post surrounded by photos

of the missing and hundreds of candles. Two women walked among the candles,

relighting all the flames that had gone out.

After

the wedding, Amy and I walked to Union Square, filled with people, candles,

and memorials. Chalked onto various monuments were slogans like ANGER, NOT

HATE and PEACE. An older white woman and a black man wearing a flag bandanna

performed a flute duet of "Glory, Glory Hallelujah." Tibetan monks walked

through the crowds. A group sang Christian prayers. At the south end of

the square, in the largest memorial, stood a peace post surrounded by photos

of the missing and hundreds of candles. Two women walked among the candles,

relighting all the flames that had gone out. Down the block, vendors were selling flag ties and t-shirts with slogans such as "America Under Attack" and "Evil Will Be Punished." A week earlier, those same vendors had been selling New York souvenirs and whatever else folks would buy.

SUNDAY

As I got dressed and noticed I had inadvertently put on a red t-shirt and blue jeans and was about to put on white socks, I began to wonder about all the red, white, and blue I was seeing. Amy came home with red, white, and blue candles to put in the window. (Actually, the store was sold out of white candles and so she bought a gold one, but I'm sure it showed support for some country's flag.)

I remember slogans from the Vietnam era such as "My country, right or wrong," and I fear that a renewed patriotism could escalate into justification for any action in pursuit of our interests, regardless of consequences. Our history includes both fighting for the noblest ideals and supporting despotic regimes.

I wanted to start selling t-shirts and decals with our planet on it, because I don't want what's best for America as much as I want what's best for the earth. I want my home to be safe from attack. I also want a world in which the other inhabitants of our planet never have a good reason to hate the U.S.A.

In the afternoon, Amy and I returned to lower Manhattan. Most of the streets had been cleared and cleaned, and the sidewalks were packed with the curious. People surrounded and took photos of the few visible symbols of the devastation, such as a severely dented and dust-covered police truck. A few people had photos taken of themselves standing next to it.

A huge crowd had gathered at the police barricade at the corner of Greenwich and Duane streets, where television news crews had set up their cameras, reflectors, and satellite dishes. A black sedan pulled up, and people whispered, "Let's look. There might be some important people coming through." Another said, "Is that Governor Pataki?" I suddenly felt less like I was at a scene of a tragedy and more like I was a groupie stuck behind the police barricades at the Oscars.

Crossing the street, I looked toward where the World Trade Center had stood. My mood changed dramatically as I saw one of the crushed and destroyed buildings adjacent to the towers. Behind it, where there had been two mammoth skyscrapers, there was nothing but clouds of smoke rising, five days after the tragedy.

Put off by the crowds, Amy and I walked north. A few streets away, police had set up a barricade in the middle of a street to cordon off an area for rescue workers. On the curb nearby sat a somber 9-year-old girl. She had baked chocolate raisin cookies for the workers and was waiting, hoping they might walk by. When someone pointed her out to the policeman on guard duty, he let her inside. With a smile on her face, she began to hand out her treats.

Union Square was filled with people again, including a jazz combo, a folk duet, sunbathers, dogs, and a woman in green body paint dressed as the Statue of Liberty. She let people pose with her, with the proceeds going to a relief charity. Nearby a trio of older Chinese women who barely spoke English had set up a stand where they sold t-shirts with a drawing of the World Trade Center and the words "America Under Attack. I Can't Believe I Got Out!"