|

Body

Art

Paper dresses with iconic images have made Sarah Caplan

a fashion poster child.

by

Lauren Parker

photos

by Marina Berio '88

Working

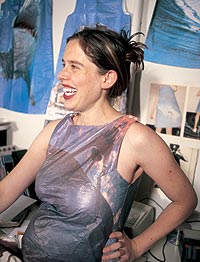

from her Manhattan design studio, a pregnant Sarah Caplan '88

proves that her innovative paper wardrobe doubles just fine

as maternity wear. An Oberlin art major-turned-clothing designer,

Caplan has created a respected niche in the fashion world with

her wearable, bold, postmodern dresses that speak volumes about

our society. Her clothing line, which evolved from poster dresses

to jackets, vests, and skirts, has attracted reviews in dozens

of media outlets. Even the esteemed Fashion Institute of Technology

houses her works in its museum's permanent collection--not bad

for an artist with little professional fashion experience. Working

from her Manhattan design studio, a pregnant Sarah Caplan '88

proves that her innovative paper wardrobe doubles just fine

as maternity wear. An Oberlin art major-turned-clothing designer,

Caplan has created a respected niche in the fashion world with

her wearable, bold, postmodern dresses that speak volumes about

our society. Her clothing line, which evolved from poster dresses

to jackets, vests, and skirts, has attracted reviews in dozens

of media outlets. Even the esteemed Fashion Institute of Technology

houses her works in its museum's permanent collection--not bad

for an artist with little professional fashion experience.

"I

remember photocopying a 1960s picture of a woman wearing a

paper dress with an image of Bob Dylan on the front, which

I had found in a book in the art museum library at Oberlin,"

Caplan says. "Thirteen years later I still have the print

and keep it on my wall for inspiration."

Caplan

put a millennial spin on the concept first introduced by

Scott Paper Company in 1966 to promote colored toilet paper

and paper towels. Half a million op-art and psychedelic-patterned

paper dresses sold for $1.25 apiece, igniting a fad that

even the Duchess of Windsor embraced.

A

paper-thin concept? Hardly. The disposable dresses of the

'60s were part of a much broader social movement. As we

evolved into a use-and-toss society, consumers became accustomed

to throwaway cutlery, diapers, and containers. Why not throwaway

fashion? While strolling through New York City eight years

ago, Caplan stumbled upon a street vendor selling one of

these vintage paper poster dresses for a mere $2. "They

were worth up to $1,000 at the time based on a Sotheby's

auction," she exclaims. "And that was before eBay!"

She

wore her acquisition to a museum opening and was photographed

by fashion trendwatcher Bill Cunningham for The New York

Times style section. "The dress had a huge image of a woman's

eye," she says. "I just couldn't believe the response it

got."

The

experience inspired her to reinvent the design classic for

the millennial set. She ditched the original disposable

paper for Tyvek, a biodegradable, water-resistant, high-density

polyethylene manufactured by DuPont that is surprisingly

durable (ever try to rip a FedEx envelope?) and machine

washable. The fabric gets softer and more wrinkled with

each wear and wash, but it lasts. Perfect for a population

that has replaced the word disposable with recyclable. The

experience inspired her to reinvent the design classic for

the millennial set. She ditched the original disposable

paper for Tyvek, a biodegradable, water-resistant, high-density

polyethylene manufactured by DuPont that is surprisingly

durable (ever try to rip a FedEx envelope?) and machine

washable. The fabric gets softer and more wrinkled with

each wear and wash, but it lasts. Perfect for a population

that has replaced the word disposable with recyclable.

She

kept the original design, an A-line cut, which is deliberately

simple and offers a wide canvas for the attention-grabbing

pictures, but flowers and psychedelia were replaced with

powerful images reflective of a bigger, faster mentality:

a satellite dish, an opened-mouth shark, the World Trade

towers, a lightning storm, and a surfer cresting a massive

wave. "It's all about speed now," Caplan says. "Things are

spinning out of control with technology and communications.

Time is out of balance."

To

suit, she named her company MPH (Miles Per Hour), emphasizing

that her designs are abstract art items first, articles

of clothing second. "This project was more of an artistic

endeavor than pure fashion design," she says. "While fashion

wasn't my number one priority in college, I always felt

it had an undeniable seductive power and could be used just

as any medium can to express artistic notions. Oberlin had

a great art department and really encouraged me to question,

think critically, delve, push the boundaries.

"I

wanted these dresses to be conceptual; something with an

idea behind them," she adds. "Not something that changed

with the whims of fashion."

An

issue of Financial Times last year credited Caplan with being

well ahead of the trend, citing a recent Paris exhibition,

Papiers a la Mode, which displayed intricate dresses made

entirely of paper. Caplan's creations sell at retail stores

in New York and through her website (www.mph-nyc.com).

For

her next designs she has several ideas, working with advertising

images among them. "I find advertising annoying, as it's

so ubiquitous. Even New York City has buckled and now allows

billboards to invade what was a pristine urban landscape."

Ads,

she says, have been boiled down to stark, recognizable imagery

("think Marlboro Man or the Nike swoosh") that need no words

or explanation. "Advertising has replaced art in its power

to sway, manipulate, and seduce us. In many cases, the ads

are confusing, yet the public has an instant, visceral response

and wants to buy into the fantasy.

"For

me, using these images on my dresses would be a commentary

on what powers are at play in our lives, what guides us

in our consumer-based culture."

Lauren

Parker is the executive

editor of Smock, a glossy publication that fuses contemporary

art with fashion, style, and design.

|