|

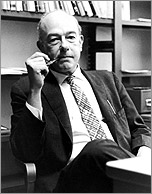

Willard van Orman Quine '30, hon. '55

1908-2000

|

|

| Willard van Ormon

Quine, the Harvard professor, one of the foremost

philosophers of the 20th

century, died on Christmas Day at age 92 in Boston

after a brief illness.

|

|

Known to his friends as Van, Willard

Quine arrived in Oberlin from his family's home

in Akron, Ohio, in 1926 after selling his cherished stamp

collection to help finance his tuition.

His

older brother Douglas had attended Oberlin, so Mr. Quine was

somewhat familiar with the campus. Among his new college friends

was a group of enthusiastic poker-players, who, while shuffling

cards one day, began to discuss their excitement about the

philosophy of Bertrand Russell. Mr.

Quine, who was captivated, imbued himself in Russell's viewpoints

and decided immediately to major in mathematics with a minor

in the philosophy of math.

In

his autobiography, The Time of My Life, he recalled his four

years at Oberlin as "idyllic." His rooming house, filled with

kindred spirits, was "an ideal setting in which to wax articulate."

Following his sophomore year, he and two friends spent the

summer crossing the continent, jumping onto moving boxcars,

and spending nights on benches or in prisons. This was the

first of the adventures that led to his lifelong insatiable

desire to travel.

By the time Mr. Quine retired, he had set foot in 113

countries in five continents. For his 90th birthday, his family

took him to North Dakota, the only state of the union he had

not visited.

After

graduating summa cum laude from Oberlin, the next stop was

Cambridge, Massachusetts, where, spurred by the economic uncertainties

of the Depression, he completed the requirements for a Harvard

doctorate in just two years under the supervision of leading

philosopher Alfred North Whitehead.

Eligible

for a yearlong, post-doctoral Sheldon Travelling Fellowship,

he married Naomi Clayton '29, and the young couple set off

for Vienna, Prague, and Warsaw, meeting the most distinguished

mathematicians of Europe. Planning carefully, they returned

to Harvard 12 months later with exactly $7 between them.

Mr.

Quine was elected as a junior member of the newly formed,

prestigious Society of Fellows, which allowed him three years

of research. In 1936 he began a teaching career at Harvard

that would last for the next four decades. He retired in 1978.

He

tried to integrate the rigorous study of logic and language

with philosophy to discover what humans can know and how

they can know it. Although not all of his peers agreed with

him, he was nevertheless considered the world's foremost

analytical philosopher, and certainly a luminary of the

academic world. Mr. Quine's position was that philosophy

was contiguous with science, not a separate, privileged

field, that could provide an independent foundation for

other areas of study.

His specialty was in mathematical logic and in the meaning

of language, and he theorized that what exists is what our

best theory says exists. He set out to define the reality

of the world and how humans fit into it. The conclusion

he arrived at was that a person could only understand the

world empirically, or through direct experience of it. He

believed that nothing that humans know lies outside the

realm of language, and so the theory of knowledge depended

upon a theory of language. His paper, "Two Dogmas of Empiricism,"

published in 1951, helped to crumble the barriers between

science and philosophy.

Aside from guest lectures on five continents, Mr. Quine

left Harvard only once, for four years, to serve in World

War II as a Navy officer deciphering communication codes

used by German submarines. His facility in languages included

not only German, but also French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese,

and a smattering of ten other languages. One of his more

than two dozen books was written in Portuguese. His magnum

opus was Quiddities, written in a style that was eminently

lucid, and, at the same time, lively, elegant, and accessible

to the layman. In his 500-page autobiography, he includes

a long segment about his friendship with Oberlin classmate

and lifelong friend Ed Haskell '28, whom he describes as

"ambitious, opinionated, contentious in the classroom, and

rather shunned as an eccentric." The author mentioned that

he often accepted speaking engagements only for the sake

of their frequent reunions.

Mr.

Quine typed his manuscripts on a 1927 Remington typewriter

he had modified by replacing characters he didn't use with

mathematical fractions. When asked why he didn't need the

question mark on his typewriter, he replied. "Well, you

see, I only deal in certainties."

Among

the hundreds of students whom he taught were the mathematician

and political satirist Tom A. Lehrer and Theodore J. Kaczynski,

later known as the "Unabomber." Mr. Quine is possibly

the only philosopher whose name appears in the Oxford

English Dictionary. The listing "Quinian" is defined as

"Of or pertaining to or characteristic of Willard van

Orman Quine or his theories." Many philosophers use "to

Quine" to repudiate a clear distinction.

Mr.

Quine had a softer side. He enjoyed a very happy second

marriage and was close to each of his children; two by

his first marriage and two by his 1948 marriage to Margerie

Boynton. He loved Dixieland jazz and played the banjo

in jazz groups. He also liked Mexican folk songs, Gilbert

& Sullivan, and playing the mandolin. A self-taught

pianist, he preferred limiting himself to only the black

keys.

Mr.

Quine was awarded an honorary doctor of letters degree

by Oberlin in 1955, and held a dozen and a half other

honorary degrees. He was recipient of the 1993 Rolf Schock

Prize in Stockholm, and the 1996 Kyoto Prize in Tokyo.

Predeceased by his wife and his former wife, he

is survived by three daughters, a son, five grandchildren,

and a great-grandchild.

--by

Mavis Clark

|