|

|||

|

Around Tappan Square On

Tour With Oberlin Steel story

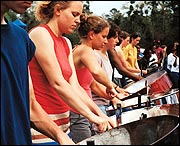

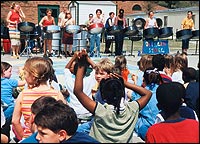

and photos by Peter Meredith ’02 The excited response from the elementary students isn’t unusual; audiences have been wild about this band ever since its first performance in 1980, when three Arts and Sciences students formed the group during winter term. Each had played in a high-school steel band called Calliope’s Children and together had brought eight pans (as the instruments are called) with them to Oberlin. Here, they called themselves the Can Consortium—after the “CC” painted on the pans by the high school band—and played their first show in a Warner Hall dance studio. “Here

we were, a bunch of people—most of whom had only recently taken

stick to pan—playing this concert that was wildly and enthusiastically

received,” recalls charter member David Dunn ’83. “People

were screaming and dancing. It was amazing!” It’s another sunny afternoon in downtown Atlanta. Dwarfed by skyscrapers, Oberlin Steel is set up in Centennial Olympic Park, where bandleader Patia Maule ’03 leans over her pan to talk to the audience. “We have four main types of pans,” she explains to the business-attired, lunch-hour crowd. She points to the smallest instruments. “These are the leads, the highest pans that generally play the melody.” Working her way down the harmonic spectrum, she introduces the seconds, the cellos, and the bass, a huge instrument consisting of six 55-gallon oil drums. Finally, she points out the “engine room,” the four-member percussion section featuring a drum set and three alternate percussionists. The sound of a steel-drum band is harder to describe than its instrumentation. The soca beat is fast and energetic, with rhythmic accents on “two-and” and “four.” The pan parts are interlocking and continuous, rarely giving the players (or audience) a chance to rest. The leads tirelessly beat out melodies and solos, while the cellos and seconds vigorously strum syncopated chords, mimicking an unrelenting guitar. The whole thing is undeniably loud. A full Trinidadian steel-drum band during Carnival has hundreds of pan players, creating a powerful sound that’s inescapably danceable. It’s

a sound that Oberlin Steel works hard to replicate. At a time when

many U.S. pan players are favoring lighter, cleaner, and quieter

arrangements, Oberlin Steel takes pride in playing party music.

The band is a mainstay at campus parties, outdoor celebrations,

and Illumination. A pan clinician who was recently on campus characterized

its sound with terms from the big-band swing era. “Sweet”

bands, he said, played light and syrupy songs, but “hot”

bands played hard-swinging songs that drove audiences crazy. On a tree-lined street in Savannah, the band members sit on a hot, cracked sidewalk, discussing hotels in which to spend the night. The conversation lasts half an hour, as members debate the importance of a kitchen versus larger beds.

“Compared to other bands I’ve been in, this one is very concerned with communication and cooperation,” says Joaquín Espinoza Goodman ’02. “It’s not just about getting gigs or getting paid.” There is a real sense of camaraderie here. Perhaps it’s due to the amount of time the group spends together—four hours a week throughout the school year and 24-7 during the spring tour. As a result, the band has developed its own set of inside jokes and catchphrases, a dialect all its own. Most members, for example, acquire nicknames by which they’re known during rehearsals. Nicknames are generally not of each member’s choosing; they’re bestowed by the band for embarrassing moments, endearing qualities, or for their potential to irk their namesake. Some members wear their numerous nicknames like a badge of honor. One bandleader, by the time she graduated in 1999, was known as Kristin “Disco Hotpants Ritchie Limelady Captain Carrot” Jones. Back

in Atlanta, Oberlin Steel is playing one of the tour’s few

air-conditioned gigs, a show at the retirement home of a band member’s

grandmother. It’s an interesting environment: the audience

is largely African American, while most of the band members are

white, something many would consider ironic given steel drumming’s

origins. Though the music changed, white aversion to it continued. As steel scholar Kristen Batson writes, “Members of the upper classes showed great distaste for the steel-band movement and viewed its members as disruptive social forces…resistance which in some cases persists today.” But

if anyone at the Atlanta retirement home found Oberlin Steel’s

racial make-up striking, they didn’t speak up. Students at

Oberlin, however, have been less sympathetic. The band has been

accused of cultural appropriation, owing largely to its predominantly

white membership. But many Oberlin Steel members deny this claim.

It’s 11 p.m. on a snowy Oberlin night. The students arrive home and begin unloading gear into their basement rehearsal room in Hales Gym. The room—called the Panyard—resembles the inside of a giant concrete shoebox, with windows near the ceiling. Walls are covered with the multicolored, spray-painted nicknames of band alumni, who each sign the wall as a last rite before graduating. Any space left over is plastered with pictures of band members and Trinidadian pan masters. Generations of pan players have now called the Oberlin Panyard home, a sentimental realization for many alumni. “Seeing people in the band now who were born while we were in it…that’s incredibly humbling,” says charter member Dunn. “The most meaningful and joyous musical experience I’ve ever had was in this band, and I’m grateful that 20 years later, students can still feel that joy.” |

|

back to top |

It’s

a muggy Georgia afternoon, and the 16 members of Oberlin Steel are

sweating their way through an outdoor performance at an Atlanta

elementary school. The students are excited; although the principal

had asked them to stay seated during the concert, several have rushed

the stage and are dancing wildly, their flailing arms barely missing

some amused teachers. As the band finishes, the kids cheer enthusiastically

and crowd around the steel drums, jostling each other for the chance

to bang away.

It’s

a muggy Georgia afternoon, and the 16 members of Oberlin Steel are

sweating their way through an outdoor performance at an Atlanta

elementary school. The students are excited; although the principal

had asked them to stay seated during the concert, several have rushed

the stage and are dancing wildly, their flailing arms barely missing

some amused teachers. As the band finishes, the kids cheer enthusiastically

and crowd around the steel drums, jostling each other for the chance

to bang away. Rarely

are decisions in Oberlin Steel made quickly. The band has a democratic

process reminiscent of Oberlin cooperatives. Though the group elects

a leader, he or she serves more as a discussion facilitator. At

a school where many musical groups are led by faculty, this is a

rarity. Oberlin Steel, though, has a culture of its own, perhaps

not surprising in a group with no Conservatory performance majors.

Rarely

are decisions in Oberlin Steel made quickly. The band has a democratic

process reminiscent of Oberlin cooperatives. Though the group elects

a leader, he or she serves more as a discussion facilitator. At

a school where many musical groups are led by faculty, this is a

rarity. Oberlin Steel, though, has a culture of its own, perhaps

not surprising in a group with no Conservatory performance majors.