|

|||

|

Looking

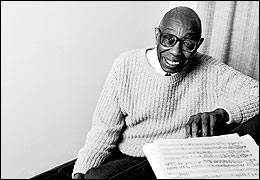

Past the Pulitzer by Tamima Friedman ’83 / photo by Arthur Paxton

Walker’s quiet demeanor belies a passion and energy that emerge from time to time as he jumps up to retrieve the score of a recent composition or speaks about things that irk him—like the Jersey tomato, just ripe for picking—that was plucked mysteriously from his garden last summer. But he grows even quieter when talking about issues that trouble him profoundly, such as why there has been little public interest in his work despite the momentous spring of 1996, when he became the first black American composer to win the Pulitzer Prize in music. His winning composition, Lilacs, a 16-minute work for soprano and orchestra, was commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and premiered in February of that year. “The fact is that with all the publicity, Lilacs has had only a few performances, one of which was at Oberlin,” Walker says. “And even if that work were not performed, there certainly is reason to expect that other works of mine might be done, or that I might be commissioned by orchestras.” Sadly,

says Walker, that hasn’t been the case—an experience that

reinforces his belief that African American classical composers

and performers lack the acceptance and recognition of their jazz

counterparts. “It really boils down to assumptions that are

made that are never fully counteracted,” he says. “Blacks

are accepted as entertainers involved in dance and singing, but

as (classical) composers and performers, we’re met with resistance—to

the point that it’s kind of a reinstatement of a ghetto.”

Walker says he was lucky in his relationship with his first publisher and champion, Paul Kapp at General Music Publishing Company. “I would give Paul a manuscript of something that hadn’t even been performed, and he would have it engraved without any cost to me.” But Walker was never interested in leaving behind a body of work to molder on a shelf. “Grants and fellowships are one thing, but performances are another,” he says. And when it comes to performances of his works, Walker believes that he has not had an easy time. Witness New York City’s music festival, A Great Day in New York, organized last year to focus public attention on the stylistic diversity of 52 living composers in greater New York. Walker was not among them. “I was never called,” he says, his irritation palpable. “The inconsistency is very disturbing. When there are opportunities to be involved in groups that are very active in contemporary music, there is no attempt to make contact with me.” Walker’s omission from the New York music festival comes as no surprise to some. “Since composers are the least profitable part of the music-world pie, they have been increasingly marginalized from the professional world,” says a prominent New York musician who asked not to be named. “The number of worthy musicians who live in obscurity is quite large, and the musical community’s sense of responsibility to its older members is nonexistent, unless there’s a buck to be made.” This sad state of affairs was brought home to Walker recently when he stumbled upon two articles on commissions awarded over the years by the New York Philharmonic and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. “I was not on the list for either, despite the fact that I’ve had five works done by the New York Philharmonic, and it’s only been six years since the Boston Symphony performed my Pulitzer Prize piece,” he says. And when it comes to recordings, Walker is not the only composer left standing in the cold. When the New York Philharmonic put together CDs of its works, he says, the only African American composer included was Duke Ellington. At the Boston Symphony Orchestra, not a single black composer was represented. “The Boston [Symphony] compilation was of their radio broadcasts. My piece from 1996 was certainly broadcast, but it was not included in the list.” Walker went to great pains to have a performance of Lilacs released after it was premiered and taped by the Boston Symphony. For months, he wracked his brain wondering how to raise $17,000 to buy one of the symphony’s broadcast tapes. But that sum covered the orchestra’s costs only; there would still be conductor and soloist fees, as well as a tape to be edited and mastered. He began to lose hope—until he met Timothy Russell, conductor of the Arizona State University Symphony Orchestra. Russell, who wanted his orchestra to perform Lilacs and had ties to Summit Records, agreed to approach the company about recording the work. “In fact, it was recorded the very day after the performance,” Walker says. “That meant I could use something of very good quality.” He

admits that it can be difficult for institutions to make choices

when they release such a limited number of CDs. “But again,

what I’m talking about is this whole kind of inconsistency.

A lot of these orchestras are involved in outreach programs. They

make a big thing of Martin Luther King Day and Black History Month,

and they think that is sufficient. It’s not.” Furthermore,

he says, the need to create cultural icons has resulted in the promotion

of just a few composers as the American composers. Despite these obstacles, Walker believes that composers today are more interested than ever in creating works that communicate, which has resulted in an enormous range of music available for study and performance. “At the moment, composers have stepped back from their so-called futuristic aspirations—stated so vociferously by composers like [Pierre] Boulez—to the point where they actually feel like they’d like to have an audience,” he says. The focus of Walker’s own compositions has been with symphony orchestras, where “you get a sizeable audience to hear your music.” He has several post-Pulitzer projects up his sleeve to create more interest in his work, including a “wonderful arrangement” with Albany Records to record his compositions and the standard piano repertoire he played in his concertizing days. Walker tapes everything himself. “I provide Albany with the finished CD,” he explains. “It’s edited and mastered. I simply send it to them with the notes, and we decide on a cover photo.” Of

his recent compositions, Walker is especially proud of Canvas,

a complex work in three movements for wind ensemble, five speaking

voices, and chorus commissioned by the North Texas University Wind

Ensemble. “I’ve also just finished a song that I’m

extremely pleased with,” he confides. “Nobody knows about

it yet.” The manuscript lies waiting on Walker’s Steinway,

a copyist due shortly to pick it up. It is a setting of And Wilt

Thou Leave Me Thus by the 16th-century poet Sir Thomas Wyatt.

Walker tried to set the poem 25 years ago but discarded his effort,

as is his habit with works he feels are not up to snuff. Then he

met cellist Yo-Yo Ma’s father-in-law, John Hornor. Does Walker have any advice for today’s up-and-coming composers? He raises his finger to his lips, ponders a moment, and replies, “Learn as much as you can about the past, and be critical of what exists in the present.” Tamima Friedman is a freelance writer and editor. She lives in Montclair, New Jersey, with her husband, Daniel Rosenblum ’83, and two daughters. |

|

back to top |

George

Walker is angry, although you wouldn’t know it from the sound

of his voice. Dressed in a dark wool suit, he is sitting in the

living room of his modest home in Montclair, New Jersey, where he

has lived for 30 years, speaking in soft-spoken tones that can barely

be heard. Other than a tennis injury that sidelined him temporarily

from his favorite sport, Walker, who turned 80 this June, shows

few signs of his age. Given his busy schedule of travel, speaking,

recording, and composing, another birthday is the last thing on

his mind. “I don’t want to think about that,” he

insists. He has just returned from engagements in Delaware and North

Carolina and is looking forward to the upcoming performance of his

Cantata by the Oratorio Society of New Jersey.

George

Walker is angry, although you wouldn’t know it from the sound

of his voice. Dressed in a dark wool suit, he is sitting in the

living room of his modest home in Montclair, New Jersey, where he

has lived for 30 years, speaking in soft-spoken tones that can barely

be heard. Other than a tennis injury that sidelined him temporarily

from his favorite sport, Walker, who turned 80 this June, shows

few signs of his age. Given his busy schedule of travel, speaking,

recording, and composing, another birthday is the last thing on

his mind. “I don’t want to think about that,” he

insists. He has just returned from engagements in Delaware and North

Carolina and is looking forward to the upcoming performance of his

Cantata by the Oratorio Society of New Jersey.